In the 33 years since President Richard M. Nixon launched the nation's "war on cancer," medical advances have turned a diagnosis once tantamount to a death sentence into an increasingly survivable disease.

Some cancers, though, have proven far more powerful than others. Among the worst: glioblastoma multiforme, or GBM. It's one of the most common and most aggressive of the 100 or so types of brain cancers, claiming 125,000 lives a year nationwide. Among its better- known victims: Chicago sportscaster Tim Weigel.

In 1975, survival typically was only about seven months. A quarter century later, it was about the same, according to the most recent federal data. Just 3 percent of people struck by glioblastoma typically live as long as five years.

But now "there's reason to be optimistic," said Dr. Maciej Lesniak, director of neurosurgical oncology at the University of Chicago Medical Center. Here's why:

*Several novel approaches to treating glioblastoma are in clinical trials. These include a new "smart" drug and a targeted drug-delivery method that recently became available in a study involving three Chicago hospitals.

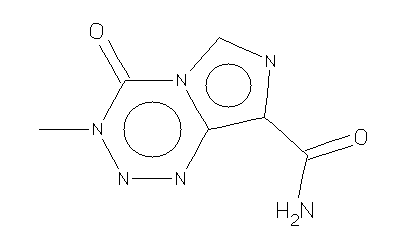

*The chemotherapy drug Temodar appears promising as a tool to buy GBM patients time.

*And a new test can help doctors pinpoint which patients will benefit from Temodar.

"There's no good time to have a GBM, but I'd certainly rather have a GBM now than at any other time," said Dr. Richard Byrne, a brain surgeon at Rush University Medical Center.

Glioblastoma's tumors are a surgeon's nightmare -- irregularly shaped, with poorly defined borders. And renegade cancer cells often hide beyond the main tumor.

"These are incredibly stubborn tumors to fight," said Dr. Glenn Lesser, an oncologist at Wake Forest University in North Carolina.

Scientists are slowly chipping away at the obstacles to treating glioblastomas. "We now have new therapies for glioblastoma that we couldn't offer patients 10 years ago," Lesniak said, "and there are more clinical trials in brain tumors than there have ever been before."

So far, though, "that really has not yet translated into better outcomes for patients." Lesser said.

'We're getting better at it'

The National Cancer Institute reports 63 ongoing clinical trials in glioblastoma alone. One involves a drug from Lake Forest-based NeoPharm being tested at hospitals, including three in Chicago -- Rush, Northwestern and the University of Chicago. Known as IL13- PE38QQR, it's a "smart drug" that zeroes in on cancer cells -- while sparing normal brain cells -- after the tumor is surgically removed.

"Previous studies with this drug have shown that it was safe and that there were some very dramatic responses in terms of eliminating residual tumor in the brain and prolonging patient life," said Byrne, lead investigator for the study at Rush.

Catheters are passed through the skull and into the brain, then a pump slowly pushes the drug solution through the tiny tubes. This lets the medication bypass the blood-brain barrier, a tight-knit layer of cells that protects the brain from chemicals and viruses in the bloodstream. The problem for brain-cancer patients: The barrier can keep out drugs that kill cancers elsewhere in the body.

"Trying to get drugs to brain tumors has been a major obstacle," Lesniak said. "But we're getting better at it."

Surgeons can now implant dime-size chemotherapeutic wafers in tumor cavities. As these Gliadel wafers dissolve over several weeks, they release a cancer-fighting drug. The drug's approval in 1996 marked the first new treatment for malignant brain tumors in 23 years, Lesniak said.

"It buys you another two to three months, at best," he said. "But two or three months can make a tremendous difference. It can mean seeing a daughter get married or a grandchild be born."

Bigger role for chemo

John Crocilla of Wood Dale had wafers implanted in August 2003, after Byrne operated on his glioblastoma -- a word Crocilla hadn't heard till his doctor explained that it's what caused numbness and tingling on his left side.

When Crocilla was diagnosed, his doctor at the time gave him three months to live. Crocilla and his wife, Paula, sought out experimental treatment at Rush combining the drug thalidomide and chemo, hoping to buy more time for the father of two sons, ages 5 and 18. Crocilla died Dec. 15 at age 48.

"The doctor gave him three months, and he had 16," Paula Crocilla said. "We had more time with him because of the treatment."

Chemotherapy is playing a bigger role in treating glioblastoma, which long was fought with surgery and radiation. At an American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in June, researchers shared results of a study that looked at standard therapy for glioblastoma with or without the early use of the chemotherapy drug Temodar. After two years, 26 percent of patients who got low doses of the capsule Temodar for several weeks at the start of treatment were alive, compared with 10 percent who got the usual care.

Doctors now can figure out which patients stand to gain from Temodar using a test that tells whether a key gene is switched off or on. If it's active, the drug had little effect. In those with the silent gene, the chance of living two years after treatment was an encouraging 46 percent.

Making the old new

A hallmark of GBM is that the tumor often returns. When it does, it can be too damaging to normal tissue to endure more radiation. That's where a device called GliaSite comes in. Approved by the FDA for brain cancer in 2001, it uses a balloon catheter filled with liquid radiation to deliver the therapy right to the tumor.

"The major benefit . . . is that a high dose of radiation may be given directly to the tumor site, while minimizing the amount of healthy brain tissue exposed to radiation," said Dr. John Chang, medical director of radiation oncology at Lutheran General Cancer Care Center in Park Ridge.

Lutheran began using GliaSite last year. The hospital also now has an intra-operative MRI, letting surgeons scan the brain during surgery, not just before. This can give a better idea of a tumor's boundaries. Intra-operative MRIs are more valuable with other brain tumors, but some GBM patients benefit, said Dr. John Ruge, a Lutheran General neurosurgeon. "If my family member has a glioblastoma and needs a complete resection, they're not going anyplace that doesn't have this," Ruge said.

Other promising leads

Gene therapy also is a hot area of research, said Dr. Jan Buckner, chairman of medical oncology at Mayo Clinic. "We're developing a modified measles virus that changes the DNA of the virus so it only enters brain tumor cells," Buckner said. "Once it's in the cell, it basically gives the brain tumor measles and kills those cells."

A U. of C. team has wrapped up research on genetically altering a cold virus, aiming it at GBM and blood vessels that feed it. If animal studies go well, Lesniak hopes to begin tests on humans as early as this year.

While these tactics hold promise, Buckner doesn't think there's one magic bullet.

But each improvement matters to people like Paula Crocilla, who's convinced that ongoing research added a precious few months to her husband's short life. That's why she wanted to return the favor.

"I agreed to have them remove John's brain tumor, and it's going to be used for cancer research," Crocilla said. "Hopefully one day, John will contribute to finding a cure."

Copyright The Chicago Sun-Times, Inc.

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved.