Abstract

Recurrent erythema multiforme is a rare disorder, clinically characterized by symmetrically distributed, erythematous, and bullous skin and mucous lesions, mainly precipitated by a preceding herpes simplex infection. In rare cases, EM presents continuous or persistent relapses, and has been related to an Epstein-Barr virus infection. We report 2 cases of severe, persistent erythema multiforme, treated with thalidomide, with complete disease suppression in both cases. Thalidomide induces immunomodulator, anti-inflammatory, and anti-angiogenic effects, and may be considered as the elective treatment of this rare variety of erythema multiforme. However, in order to avoid neuropathic side effects, patients under thalidomide therapy should be monitored every 6 months with nerve conduction studies while taking the drug.

BACKGROUND

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute, self-limited, infammatory skin disorder characterized by symmetrically distributed, erythematous, and bullous skin and mucous lesions, mainly precipitated by a preceding herpes simplex infection. This condition resolves within 12 weeks and many patients experience more than one episode.

In rare cases, EM presents continuous relapses. The first case of recurrent erythema multiforme (EM) was reported in 1977 by Chapman et al. (1), in a woman with inflammatory bowel disease. Skin lesions appeared at the same time that the activity of the bowel disease increased. In 1985, Leigh et al. (2) reported three patients with lesions that never disappeared, defining the features of this persistent variety of EM and individualizing from recurrent EM. In this way, Leigh et al. (2) described two subgroups of EM depending of the type of relapses: a) recurrent EM, in which multiple relapses occur every year, mucosal involvement is present only in a minority of patients, and each attack lasts 1-2 weeks as in classic EM; and b) persistent EM or continuous EM, with uninterrupted appearance of typical papular bullous or necrotic atypical lesions, and mucosal involvement is the rule. These cases are exceedingly rare.

To date, only a few cases of persistent EM have been published in the literature. We report two cases of persistent EM treated by thalidomide with excellent results, achieving the complete stop of relapses. We also confirm that a viral infection by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) plays an important role in the development of persistent EM.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1. The first patient was a 55 year old woman with a 10 year history of disseminated macules, vesicobullous, and necrotic lesions associated with erosive and bullous lesions on the lower extremities (Fig. 1). For the 5 years leading up to our treatment, relapses were persistent and severe, needing hospital assistance every 1-2 weeks in the intensive care unit, with great morbidity and psychological alterations. She had been treated with oral and intravenous perfusion of acyclovir, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, azathioprine, cyclosporin, and IV immunoglobulins, without any success.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

Results from routine blood and biochemical tests were normal, but further tests revealed counts of 12,000 leukocytes, with 75% of PMN, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 80 mm/hr, and C3 0.6 mg/L were found. Serological tests to HSV type I and II were negative. Epstein-Ban" virus serological tests were positive, with Anti-EBV VCA IgG 1/2560, EA IgG 1/1040, and EBNA IgG 1/16. Histological examination revealed an intense perivascular and mid-dermis mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figs. 2 and 3). Direct immunofluorescence showed IgM and C3 granular deposits in upper dermal blood vessels. Chest X-ray and abdominal echography were normal. Carcinoembryonic antigen and alpha-fetoprotein were within normal values.

[FIGURES 2-3 OMITTED]

The patient was treated by thalidomide, 200 mg/day, with complete resolution of the lesions after 15 days of treatment. Dosage was then reduced to 100 and 50 mg/day, without relapses. Therapy was maintained during one year, but sometimes was eventually stopped with relapses of lesions. After 2 years of follow-up, treatment was stopped because the patient showed a thalidomide-induced neuropathy, with clinical and electrophysiologic-typical abnormalities. At this moment, the patient is treated with oral prednisone associated to oral cyclosporin, with a worse control of the relapses than with thalidomide.

Case 2. A 39 year old woman had a history of continuous skin eruptions, with erosive and bullae lesions on the lips and papular-necrotic lesions on the extremities and genital area during the last 3 years (Fig. 4). These lesions were resistant to oral corticosteroids, relapsing with dosages lower than 20 mg/day. Residual hypopigmented scars were present on lips and extremities.

Histological examination demonstrated similar changes to patient number 1. Blood and biochemical laboratory findings showed normal values, but the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 40 mm/hr. Serological tests for Epstein-Barr virus were positive, with Anti-EBV VCA IgG 1/1280, EA IgG 1/1040, and EBNA IgG 1/8. Other serological tests were negative. Carcinoembryonic antigen and alpha-fetoprotein were within normal values. Chest X-ray and abdominal echography were also normal.

The patient was treated with thalidomide, 200 mg/day, obtaining the same excellent response as patient number 1. After 15 days of treatment, dosage was reduced to 100 mg/day, without recurrent lesions. 6 months after the start of this treatment, the patient has not shown any recurrence or side effects while maintaining a dosage of 50 mg/day.

DISCUSSION

Persistent EM treatment is discouraging, and although several therapies like acyclovir, colchicine, dapsone, anti-malarials, azathioprine, cimetidine, levamisole, potassium iodide, cyclosporin, and human immunoglobulins have been tried to avoid lesion appearance, results are inconstant (3). The difficulties in persistent EM therapy come from our poor knowledge of its etiology.

In classic and recurrent EM, the relationship with HSV infection is well documented (4), and HSV is now accepted as the most common precipitating factor. Schofield et al. (3) have reported a definitive temporal relationship between HSV infection (usually labial) and recurrent EM in 71% of patients. For this reason, many patients can effectively suppress their recurrent EM with a short-course of oral acyclovir, particularly when there is a clear-cut association with HSV infection.

Persistent EM may be regarded as the result of a continuous incitement by different antigenic materials, such as Epstein-Barr virus infection (5-6), underlying malignancy (7), and chronic inflammatory bowel disease (1) (See Table 1).

In particular, Drago et al. (6) suggested that keratinocytes may be infected directly by EBV and that the epithelial life cycle of EBV may depend on their differentiation. This justifies that acyclovir therapy controls a large number of recurrent and persistent EM cases, even in cases with a non-proven relationship with herpes virus infection (8). Acyclovir was found to be the most useful first-line treatment, with 55% of patients deriving benefit from continuous oral acyclovir. In some cases of persistent EM, systemic administration of steroids may enhance viral replication and immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine may be required to control persistent EM.

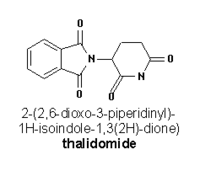

Thalidomide was initially used in Europe and Canada as a sedative and antiemetic for pregnant women in 1950s; however, its use was terminated after severe teratogenic effects were recognized in 1960s. Despite this onerous reputation, was approved by the FDA in 1998 for the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum. Since then, its off-label uses have proliferated and thalidomide has shown to be effective in the treatment of several dermatologic diseases, such as lepra reactions, actinic prurigo, discoid lupus erythematosus, and recurrent aphthosis due to Behcet's disease or to HIV infection, prurigo nodularis or Jessner's lymphocytic infiltration of the skin (9).

Thalidomide was introduced in recurrent and persistent EM in the 80s, in cases resistant to acyclovir therapy (see Table 2). There are only a few previous reports of the effectiveness of thalidomide in EM. Although Bahmer et al. (10) in 1982 and Naafs et al. (11) in 1985 pointed out the effectiveness of thalidomide in EM, the most important study corresponded to Cherouati et al. (12) in 1996, who treated 20 cases of classical EM and 6 of recurrent EM with thalidomide. Pinto et al. (13) observed a dramatic response to thalidomide in a patient affected of recurrent EM associated with autoreactivity to 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone. In all reported cases, the drug was most effective with a dosage of 100 mg daily and recurrences occurred when dosage was reduced to 25 mg daily. Remission of the disease was observed after 7-14 days of therapy, and administration was prolonged for 6-12 months.

Although its precise mode of action is unknown, thalidomide produces immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and anti-angiogenic effects (9,14). Thalidomide is currently well known as an inflammatory reaction modifier, acting as immunomodulator in several processes, many of them with cutaneous manifestations. This immunomodulatory activity is completely different than corticosteroid, cyclosporin, and pentoxifylline effects. Thalidomide inhibits chemotaxis and phagocytosis, and modulates the relation among CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, with a potent in vitro stimulant effect on CD8+ lymphocytes. Thalidomide has an anti-inflammatory effect reducing neutrophils and monocyte chemotaxis, reducing superoxide radical production, and reducing C1q synthesis. Regarding cytokine activity, the inhibition of alpha tumor necrosis factor (TNF-a) synthesis is the key to the immunomodulator properties of thalidomide (15), but sometimes thalidomide can paradoxically enhance TNF-a levels, as Wolkenstein et al. (16) have observed in cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis. The mechanism underlining this dual effect on TNF-a levels are still unknown. Thalidomide can also enhance or diminish IL-12 production by peripheral blood mononuclear human cells and monocytes. IL-4 and IL-5 are also enhanced by thalidomide (17).

Thalidomide is also an inhibitor of angiogenesis and this effect is particularly interesting in the anti-tumor action induced by thalidomide in Kaposi sarcoma (18). This activity is independent from the action on TNF-a , and is mainly due to the inhibition of angiogenic factor synthesis like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and beta fibroblastic growth factor-2 (FGF-b) (14,17-19).

However, the clinical use of thalidomide is limited by its side effects. The current development of secure anti-conceptive methods has led to a reduced incidence of teratogenicity, but an irreversible peripheral neuropathy associated to thalidomide has become the most important adverse effect. The incidence of the neuropathy has recently been assessed between 21% and 50% (20). Individual susceptibilities with possible genetic predisposition seem to be more important than daily dosage and duration of thalidomide therapy (21). Clinical features of thalidomide-induced neuropathy include symmetrical distal painful paresthesia and sometimes sensory loss of the lower limbs. Neurologic examination reveals paresthesia and hypoesthesia of fingers and toes, leg cramps, plantar dysesthesia, and stocking sensory loss.

For these reasons, some persistent EM patients treated with thalidomide have to stop the therapy because of the evidence of neuropathy (22), mainly due to long-term drug administration. In order to avoid neuropathic side effects, patients under thalidomide therapy should be monitored every 6 months with nerve conduction studies while taking the drug.

In conclusion, thalidomide may be considered the choice election treatment for persistent or continuous EM. Although some side effects may appear, the excellent response justifies its use when other treatments have failed. A low dose of 25 mg/day can reduce the secondary neuropathy. However, the low incidence of persistent EM makes it difficult to established controlled trials to determine the true efficacy of thalidomide in treating this condition.

REFERENCES

(1.) Chapman RS, Forsyth A, MacQueen A. Erythema multiforme in association with active ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Dermatologica, 1977, 154, 32-38.

(2.) Leigh IM, Mowbray JF, Levene GM.: Recurrent and continuous erytehma multiforme: a clinical and immunological study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol., 1985, 10, 58-67.

(3.) Schofield JK, Tatnall FM, Leigh JM.: Recurrent erythema multiforme: clinical features and treatment in a large series of patients. Br. J. Dermatol., 1993, 128, 542-545.

(4.) Brice SL, Krzemien D, Weston WL, Huff JC: Detection of herpes simplex virus DNA in cutaneous lesions of erythema multiforme. J. Invest. Dermatol., 1989, 93, 183-187.

(5.) Drago F, Rogmanoli L, Loj A.: Epstein-Barr virus related persistent erythema multiforme in chronic fatigue sindrome. Arch. Dermatol., 1992, 128, 217-222.

(6.) Drago F, Parodi A, Rebora A.: Persistent erythema multiforme: report of two new cases and review of literature. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol., 1995, 33, 366-369.

(7.) Davidson DM, Jegasothy BV: Atypical erythema multiforme: a marker of malignancy?. Cutis, 1980, 26, 276-278.

(8.) Tatnall FM, Schofield JK, Proby C, Leigh IM: Double blind placebo controlled trial of continuous acyclovir in recurrent erythema multiforme. Br. J. Dermatol., 1991, 125 (Suppl 38), 29.

(9.) Laffitte E, Revuz J.: Thalidomide. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol, 2000, 127, 603-613.

(10.) Bahmer FA, Zaun H, Luszpinski P.: Thalidomide treatment of recurrent erythema multiforme. Acta Derma. Venereol (Stockh), 1982, 62, 449-450.

(11.) Naafs B, Farber WR: Thalidomide therapy. An open trial. Int. J. Dermatol., 1985, 24, 131-134.

(12.) Cherouati K, Claudy A, Souteyrand P et al: Treatment by thalidomide of chronic multiforme erythema. Its recurrent and continuous variants. A retrospective study of 26 patients. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol., 1996, 123, 375-377.

(13.) Pinto JS, Sobrinho L, da Silva MB: Erythema multiforme associated with autoreactivity to 17-hydroxyprogesterone. Dermatologica, 1990, 180, 146-150.

(14.) Roujeau JC: Treatment of severe drug eruption. J.Dermatol., 1999, 26, 718-722.

(15.) Zwingenberger K, Wnendt S.: Immunomodulation by thalidomide: systematic review of the literature and unpublished observations. J. Inflamm., 1996, 177-211.

(16.) Wolkenstein P, Latarjet J, Roujeau JC et al: Randomised comparison of thalidomide versus placebo in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet, 1998, 352, 1586-1589.

(17.) Klausner J, Freedman V, Kaplan G.: Thalidomide as an inhibitor anti-TNFalpha: implications for clinical use. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol., 1996, 81, 219-223.

(18.) Pizarro A, Garcia-Tobaruela A, Herranz P, Pinilla J.: Thalidomide as an inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor alpha production: a word of caution. Int. J. Dermatol., 1999, 38, 76-77.

(19.) Bauer K, Dixon S, Figg W: Inhibition of angiogenesis by thalidomide requires metabolic activation, which is species-dependent. Biochem. Pharmacol 1998, 55, 1827-1834.

(20.) Ochonisky S, Verroust J, Bastiji-Garin S, Gherardi R, Revuz J.: Thalidomide neuropathy incidence and clinicoelectrophysiologic findings in 42 patients. Arch. Dermatol., 1994, 130, 66-69.

(21.) Harland C. Stevenson G, Marsden J: Thalidomide-induced neuropathy and genetic difference in drug metabolism. Eur. Clin. Pharmacol, 1995, 49, 1-6.

(22.) Moisson YF, Janier M, Civatte J: Thalidomide for recurrent erythema multiforme. Br. J. Dermatol., 1992, 126, 92-93.

Julian S. Conejo-Mir

Avda Republica Argentina 22-Bis, 2A

Seville 41011. Spain

Fax: +34.955.01.3473

E-mail: jsconejo@hvr.sas.junta-andalucia.es

JULIAN S. CONEJO-MIR MD, SUSANA DEL CANTO MD, MIGUEL ANGEL MUNOZ MD, LOURDES RODRIGUEZ-FREIRE MD, AMALIA SERRANO MD, CARLOS HERNANDEZ MD, AGUEDA PULPILLO MD

DEPARTMENT OF DERMATOLOGY, VIRGEN DEL ROCIO UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL, SEVILLE, SPAIN

COPYRIGHT 2003 Journal of Drugs in Dermatology

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group