Study objectives: Thalidomide therapy has been shown to modify granulomatous diseases, such as tuberculosis and leprosy. Lupus pernio is a skin manifestation of sarcoidosis that does not remit spontaneously, and was used as a marker of efficacy of thalidomide for sarcoidosis.

Design: An open-label, dose-escalation trial of thalidomide.

Setting: Patients were seen at one of four specialized sarcoidosis clinics in the United States.

Patients: Fifteen patients with lupus pernio and other manifestations of sarcoidosis unresponsive to prior therapy were enrolled.

Interventions: Skin lesions were assessed with visual examination by the treating physician, and photographic evaluation by a blinded panel of physicians reviewing photographs of the lesions before and after therapy.

Measurements and results: Fourteen patients completed 4 months of therapy. All patients experienced some improvement in their skin lesions subjectively, and 10 of 12 evaluable patients showed improvement using photograph scoring. Five patients were better after 1 month (treated with 50 mg/d of thalidomide), seven more patients improved after 2 months (treated with 100 mg/d of thalidomide in the second month), and two patients required an additional month of 200 mg of thalidomide to achieve a response. Patients reported increased somnolence (n = 9), numbness (n = 7), dizziness (n = 2), constipation (n = 6), rash (n = 1), and increasing shortness of breath (n = 1). One patient discontinued therapy because of new-onset dyspnea, due to probably unrelated new-onset congestive heart failure.

Conclusion: Thalidomide was an effective form of treatment for chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis. The drug was well tolerated and may be a useful alternative to systemic corticosteroids.

Key words: corticosteroids; lupus pernio; sarcoidosis; thalidomide; tumor necrosis factor

Abbreviations: IL = interleukin; SURT = sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract; TNF = tumor necrosis factor

**********

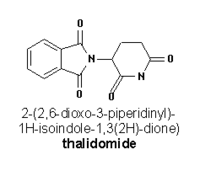

Thalidomide was introduced in 1957 as a sedative and later an antiemetic. It was subsequently found to have teratogenic effects that led to the withdrawal of the drug. However, thalidomide has subsequently been found to be effective in treating the lepromatous reaction in leprosy, (1) and it has been studied as an immumodulator for several conditions. (2-4) It has also been shown to have antiangiogenic properties, which have led to its use in malignancy, especially multiple myeloma. (5) In tuberculosis, it has been found to reduce the granulomatous response. (6,7)

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease characterized by enhanced lymphocyte and macrophage activity, (8,9) which is usually classified as a T-helper type 1 response. Among the inflammatory reactions is enhanced tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-[alpha] release by alveolar macrophages retrieved by BAL from patients with disease. (10,11) Thalidomide attenuates the release of TNF-[alpha]. (12) There have been case reports (13,14) of the use of thalidomide for sarcoidosis.

Lupus pernio is a unique disfiguring skin involvement of the face characteristic of sarcoidosis. (8) It is a chronic form of the disease and is associated with a low rate of resolution over 2 years.(15) Patients with lupus pernio are usually treated with corticosteroids and other steroid-sparing agents with limited success. (16) Lupus pernio is a form of cutaneous sarcoidosis that provides easy evaluation of therapeutic efficacy. Therefore, patients with lupus pernio were entered into an open-labeled, dose-escalation study of thalidomide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients had known sarcoidosis and skin lesions consistent with lupus pernio unresponsive to previous treatment with corticosteroids. Patients were recruited from four medical centers, and all provided informed consent. All patients were counseled regarding pregnancy, with strict precautions instituted to avoid pregnancy while receiving the agent. Men were instructed to use barrier methods, and all women were at least 2 years postmenopausal or had surgical sterilization.

Patients underwent an initial evaluation, including a focused history and physical examination to document sarcoidosis organ involvement using an organ-assessment instrument. (17) Patients also underwent spirometry to measure FVC, and the predicted values were based on age, race, gender, and height. (18)

Patients received an open-labeled dose escalation of thalidomide for 4 months. The schedule was 50 mg at night for 1 month, and 100 mg at night during the second month. For the final 2 months, the dose was doubled to 200 mg at night. If toxicity developed, the dose was reduced by one level.

Patients' skin lesions were assessed by three methods. A general impression was made by the treating physician and the patient as to whether the lesions were worse, the same, better, or resolved. The physician was also asked to draw the lesions of the face, the number of lesions were counted, and their properties, including color and depth, were noted. Finally, photographs were made using a digital camera. The images were stored, and the same views were compared from the initial visit and after 4 months of therapy. For each patient, a single image of the most obvious lesion was compared before and after therapy. The images were placed side by side in random order, and the investigators were asked to vote indicating which photograph was the initial lesion. Figures 1, 2 show examples of a lupus pernio skin lesion on the face (initial images [left, A] and follow-up lesions [right, B]).

[FIGURES 1-2 OMITTED]

All patients were screened for toxicity. A specific series of questions regarding specific toxicities (eg, somnolence) were asked. Patients also reported all adverse events, whether likely to be drug related or not. Finally, patients were evaluated for peripheral neuropathy by a Vibratron II (Physitemp Instruments; Clifton, NJ). Vibratory threshold was determined before and after therapy using the same finger for all examinations. (19)

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were made on paired data using paired Wilcoxon analysis. Calculations were made using software (MedCalc version 5.00; MedCalc; Mariakerke, Belgium). A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Fifteen patients were enrolled into the study. All patients had previously received corticosteroids, and two patients were maintained on prednisone, 10 mg/d, during the course of the study. An additional patient was treated by her primary physician during month 3 with a 4-day course of prednisone, 40 mg/d, for an acute asthmatic bronchitis followed by prednisone at 5 mg/d. Although most patients had received one or more steroid-sparing agents in the past, no patients were receiving these drugs at the time of entry into the study. No patients had modifications of their regimen for sarcoidosis in the 3 months prior to study entry.

One patient received only 3 weeks of therapy (at 50 mg/d) before experiencing shortness of breath. The thalidomide was immediately discontinued, and he was subsequently found to have new-onset congestive heart failure secondary to a recent myocardial infarction, presumed to be due to his known hyperlipidemia. He was withdrawn from the study and excluded from further analysis.

The remaining 14 patients received thalidomide for 4 months. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the patients who completed the study. Most of the patients were African-American women. We included organ involvement in addition to skin disease. Definite or probable lung involvement was documented in 12 patients. Definite or probable sinus involvement was reported in 8 patients, over half of those studied. No other organ involvement was common; therefore, further analysis was not performed on the response of these organs to thalidomide.

All patients treated for 4 months responded to treatment with reductions in their skin lesions reported by both the physician and patient. Five patients responded to 50 mg/d, seven more patients responded to 100 mg/d, while two patients did not respond until placed on 9.00 mg/d (third month of therapy). The number of skin lesions on the face were counted and compared. The individual patient counts are shown in Figure 3. There was a significant drop from the initial counts (median, 7.5 lesions; range, 1 to 13 lesions) compared to counts after 4 months of therapy (median, 3.5 lesions; range, 1 to 10; p < 0.01). One month after therapy withdrawal, four patients had an increased number of lesions, but one patient noted further lesion reduction. The number of lesions counted 1 month after stopping therapy (median, 4.5 lesions; range, 1 to 10 lesions) was not significantly different from the count at the end of 4 months of therapy.

[FIGURE 3 OMITTED]

Comparative digital photographs were read blindly by three investigators unaware of the order of the slides (Fig 1). Of the 19. patients with adequate pretherapy and posttherapy photographs, the photographs of 2 patients were deemed to show no differences by all three readers. Of the remaining 10 patients, the lesions appeared improved in the follow-up photographs.

Information on other organ manifestations from sarcoidosis was also collected. Not all patients underwent chest radiography on entry into the study. Of those patients who did undergo chest radiography, the findings of two were normal, four had hilar involvement alone, one had hilar and parenchymal disease, one had parenchymal disease alone, and two had significant fibrosis. There was no change in the chest radiograph during therapy for these patients. All patients had their FVC measured initially and after treatment. The mean FVC after therapy was 2.35 L (range, 1.61 to 4.19 L) was not statistically different from the pretreatment measurements (Table 1). In only two patients did the treating physician report that lung involvement was better with therapy. Symptomatic sinus disease was reported by eight patients at the initial evaluation. The sinus disease was believed to be perhaps due to the sarcoidosis, since no other cause was identified. Four of these patients reported significant symptomatic improvement during thalidomide treatment. This was reflected by a reduction in the need for treatment with nasal steroids and antibiotics for sinus infection.

Table 2 summarizes the major toxicities associated with the use of thalidomide. We report the dosage at which they were first encountered. These complaints were specifically sought by questionnaire. Although several complaints were noted, only two patients required dose reduction, one for somnolence and the other for numbness in the hands. Both patients' symptoms improved with the reduced dosage. Nine patients (64%) complained of daytime somnolence. Although many patients noted this even at the lowest dose of 50 mg, only one patient had the dose reduced because of somnolence. For four patients, continuation of drug was associated with reduction of daytime somnolence. Vibratron II readings (mean [+ or -] SD) were not significantly different between the initial readings (1.9 [+ or -] 0.92 vibration units) and follow-up readings at 4 months (1.7 [+ or -] 0.62 vibration units). There was no difference between baseline and when numbness was experienced. One patient had a pituitary adenoma detected during the course of the study. This was not believed to be related to thalidomide therapy.

DISCUSSION

The use of thalidomide was associated with significant subjective improvement in the skin lesion lupus pernio in patients with sarcoidosis. All patients had improvement in the number or size of their lesions, although all patients still had at least one lesion at the end of the study. Objective improvement was assessed using photographs of the lesions before and after therapy. In 10 of 12 evaluable cases, the lesions were scored as better after therapy by a panel blinded to treatment. Patients responded to 100 to 200 mg/d of thalidomide. Although side effects were commonly encountered, they rarely led to dose modification.

As previously reported for lupus pernio, all patients in this study had persistent lesions despite previous treatment with corticosteroids and other agents. (8,15) This form of cutaneous sarcoidosis is especially difficult to treat, and alternative treatments are usually sought. (16) Intralesional corticosteroids are not recommended for routine management because of the risk of skin and soft-tissue atrophy. In one patient, prior intrallesional steroids had led to some disfigurement of the cheek. Unfortunately, the lupus pernio still recurred in the area of the injection, but did respond to thalidomide. Eight of the patients had sinus symptoms that were believed to be consistent with sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract (SURT). SURT has been associated with lupus pernio. SURT is also a chronic form of sarcoidosis (15) that can be difficult to treat. (20,21) Active SURT was diagnosed in eight patients, and half of these patients had significant improvement of their symptoms during the course of the study as assessed by patient complaints and use of medications for sinus disease.

The mechanism of action of thalidomide in chronic granulomatous disease is unclear. It has been reported as useful in patients with sarcoidosis (13) and tuberculosis. (7) In a murine model of tuberculosis, thalidomide was associated with suppressed TNF release from the lung. (22) In tuberculosis patients, treatment of patients with thalidomide was associated with reduction of TNF levels. (7) In AIDS patients with aphthous ulcers, TNF release triggered by HIV was reduced by thalidomide. (23) Other in vitro studies (12,24) found thalidomide blocked the release of TNF from alveolar macrophages. Enhanced release of TNF by alveolar macrophages from patients with sarcoidosis has been reported. (10,11) This release decreased after patients are treated with either corticosteroids or methotrexate. (25) Increased levels of interleukin (IL)-12 have been reported in patients with sarcoidosis. (26) Thalidomide has been found to suppress IL-12 released by peripheral blood monocytes stimulated with heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus and lipopolysaccharide, (27) but not when stimulated by cross-linking T-cell receptor. (28,27) There were no changes in IL-12 levels in the lung in the murine tuberculosis model. (22)

Side effects encountered in this study were similar but more frequent than that reported in other studies. (5,23,29) An exception was rash, which occurred in only one patient in this study. Rash has been reported by > 20% of patients in other studies. (5,23) These skin lesions included erythema nodosum, which was seen in patients with Behcet's syndrome treated with thalidomide. (29) Numbness was frequently reported in this study, but led to drug reduction in only one patient. The Vibratron II device had been suggested as a means to detect early neuropathy (19) but was not useful in this study. The complaint of numbness was subjective and may have been overreported, since there was no placebo arm of the study. In the study of HIV-associated aphthous ulcers, peripheral neuropathy was encountered as frequently in the placebo group (5 of 28 patients) as in the treated group (7 of 29 patients). (23)

Studies (5,23,29) of thalidomide have employed doses ranging from 100 to 800 mg/d. The dose necessary to treat sarcoidosis is unclear from the prior reports, (13,14) which used various treatment regimens from 100 to 400 mg/d. We chose to start at a lower dose with a scheduled dose escalation. The onset of action of the drug was fairly rapid, and most patients have a response within 2 months. This response was more rapid than seen with methotrexate, which usually requires [greater than or equal to] 6 months to become effective. (30)

In summary, thalidomide therapy was effective for lupus pernio in patients with chronic sarcoidosis. Its onset of action was relatively rapid and was well tolerated. Although thalidomide appeared effective for skin and sinus disease, its effect on pulmonary disease and other manifestations of sarcoidosis are not yet known. Given its low toxicity, thalidomide therapy should be considered as an alternative to corticosteroids and other agents for sarcoidosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT: The authors thank Andrew Zeitlin and Celgene Corporation for helping to design safety monitoring and for financial support. We also thank Donna Winget, Susan D'Alessandro, Marilyn Marshall, Joanne Steimel, and Eileen Bowen for their technical support.

REFERENCES

(1) Sheskin J. Thalidomide in the treatment of lepra reaction. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1965; 6:303-306

(2) Forsyth CJ, Cremer PD, Torzillo P, et al. Thalidomide responsive chronic pulmonary GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 1996; 17:291-293

(3) Marriott JB, Cookson S, Carlin E, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled phase II trial of thalidomide in asymptomatic HIV-positive patients: clinical tolerance and effect on activation markers and cytokines. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1997; 13:1625-1631

(4) Uthoff K, Zehr KJ, Gaudin PB, et al. Thalidomide as replacement for steroids in immunosuppression after lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 1995; 59:277-282

(5) Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, et al. Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:1565-1571

(6) Moreira AL, Tsenova-Berkova L, Wang J, et al. Effect of cytokine modulation by thalidomide on the granulomatous response in murine tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis 1997; 78:47-55

(7) Tramontana JM, Utaipat U, Molloy A, et al. Thalidomide treatment reduces tumor necrosis factor [alpha] production and enhances weight gain in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Mol Med 1995; 1:384-397

(8) Statement on sarcoidosis: Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:736-755

(9) Thomas PD, Hunninghake GW. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 135: 747-760

(10) Pueringer RJ, Schwartz DA, Dayton CS, et al. The relationship between alveolar macrophage TNF, IL-1, and PG[E.sub.2] release, alveolitis, and disease severity in sarcoidosis. Chest 1993; 103:832-838

(11) Baughman RP, Strohofer SA, Buchsbaum J, et al. Release of tumor necrosis factor by alveolar macrophages of patients with sarcoidosis. J Lab Clin Med 1990; 115:36-42

(12) Tavares JL, Wangoo A, Dilworth P, et al. Thalidomide reduces tumour necrosis factor-[alpha] production by human alveolar macrophages. Respir Med 1997; 91:31-39

(13) Carlesimo M, Giustini S, Rossi A, et al. Treatment of cutaneous and pulmonary sarcoidosis with thalidomide. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32:866-869

(14) Lee JB, Koblenzer PS. Disfiguring cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis treated with thalidomide: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 39:835-838

(15) Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med 1983; 208:525-533

(16) Baughman RP, Lower EE. Alternatives to cortieosteroids in the treatment of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis 1997; 14:121-130

(17) Judson MA, Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, et al. Defining organ involvement in sarcoidosis: the ACCESS proposed instrument. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:75-86

(18) Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 159:179-187

(19) Gerr FE, Letz R. Reliability of a widely used test of peripheral cutaneous vibration sensitivity and a comparison of two testing protocols. Br J Ind Med 1988; 45:635-639

(20) Fenton DA, Shaw M, Black MN. Invasive nasal sarcoidosis treated with methotrexate. Clin Exp Dermatol 1985; 10: 279-283

(21) Zeitlin JF, Tami TA, Baughman RP, et al. Nasal and sinus manifestations of sarcoidosis. Am J Rhinol 2000; 14:157-161

(22) Moreira AL, Tsenova Berkova L, Wang J, et al. Effect of cytokine modulation by thalidomide on the granulomatous response in murine tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis 1997; 78:47-55

(23) Jacobson JM, Greenspan JS, Spritzler J, et al. Thalidomide for the treatment of oral aphthous ulcers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:1487-1493

(24) Rowland TL, McHugh SM, Deighton J, et al. Differential regulation by thalidomide and dexamethasone of cytokine expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immunopharmacology 1998; 40:11-20

(25) Baughman RP, Lower EE. The effect of corticosteroid or methotrexate therapy on lung lymphocytes and macrophages in sarcoidosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 142:1268-1271

(26) Moller DR, Forman JD, Liu MC, et al. Enhanced expression of IL-12 associated with Th1 cytokine profiles in active pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Immunol 1996; 156:4952-4960

(27) Moller DR, Wysocka M, Greenlee BM, et al. Inhibition of IL-12 production by thalidomide. J Immunol 1997; 159: 5157-5161

(28) Corral LG, Haslett PA, Muller GW, et al. Differential cytokine modulation and T cell activation by two distinct classes of thalidomide analogues that are potent inhibitors of TNF-[alpha]. J Immunol 1999; 163:380-386

(29) Hamuryudan V, Mat C, Saip S, et al. Thalidomide in the treatment of the mucocutaneous lesions of the Behcet syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1998; 128:443-450

(30) Lower EE, Baughman RP. The use of low dose methotrexate in refractory sarcoidosis. Am J Med Sci 1990; 299:153-157

* From the Department of Internal Medicine (Drs. Baughman and Lower), University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH; Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine (Dr. Judson), Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC; Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine (Dr. Teirstein), Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY; and Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine (Dr. Moller), Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

Supported in part by Celgene Corporation.

Manuscript received June 15, 2001; revision accepted November 16, 2001.

Correspondence to: Robert P. Baughman, MD, FCCP, Holmes 1001, Eden Ave and Albert Sabin Way, Cincinnati OH 45267-0564; e-mail: Bob.Baughman@uc.edu

COPYRIGHT 2002 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group