ABSTRACT

A case of deep-vein thrombosis is reported in a female patient with multibacillary leprosy who received pulses of dexainethasone and cyclophosphamide for recurrent ENL that had not responded to prednisone and thalidomide.

RÉSUMÉ

Un cas de thrombose veineuse profonde est rapporté chez une patiente souffrant de lèpre multibacillaire, qui reçut des traitements flash de dexaméthasone et de cyclophosphamide pour traiter un érythème noueux lépreux et qui n'a pas répondu à la prednisone et la thalidomide.

RESUMEN

Se reporta un caso de trombosis venosa profunda en una paciente con lepra multibacilar que recibió pulsos de dexametasona y ciclofosfamida debido a una reacción tipo ENL recurrente que no había respondido al tratamiento con prednisona y talidomida.

TO THE EDITOR:

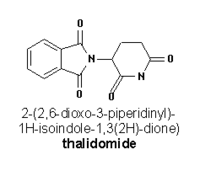

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is an important complication of several disorders and may sometimes occur spontaneously. An impaired fibrinolytic system (5), presence of lupus anti-coagulant activity (14) or increased levels of proinflammatory procoagulant cytokines (4) have all been linked to it. Cancer, surgery, fractures, puerperium, immobilization, paralysis, use of oral contraceptives, and anti-phospholipid syndrome (10), deficiencies of anti-thrombin, protein C, protein S and factor V Leiden, a mutation in coagulation factor, dysfibrogenemia and hyperhomocysteinemia (5) may be responsible for DVT. It is not a known complication of leprosy or lepra reactions and has not been reported in erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) patients receiving thalidomide. Thalidomide, a sedative drug, has been in use for management of recurrent/severe ENL due to its anti-inflammatory properties which are attributed to inhibition of inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (6), vascular endothelial derived growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (b FGF) in RNA processing (2, 6). It is also used in malignancies such as multiple myeloma (MM) and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (2, 13).

A higher incidence of deep vein thrombosis has been observed in cancer patients receiving thalidomide (12), and the incidence increases several folds when thalidomide is combined with other chemo-therapcutic agents (8, 15).

We report here a case of difficult to control recurrent ENL on treatment with oral prednisolone and thalidomide, who developed DVT when dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide (DCP) pulse was given additionally.

CASE REPORT

A 37-yr-old female patient was hospitalized with difficult to control severe and recurrent ENL. She was being treated at a peripheral health care center with multibacillary multidrug therapy (MB-MDT) for the last one year and prednisolone 40 mg/day for the past three months without adequate control of ENL. She had already developed iatrogenic cushingoid syndrome.

She had high fever, myalgia, arthralgia, recurrent crops of tender and necrotic ENL lesions, and ulnar nerve neuritis. Initially, her prednisolone dose was increased to 60 mg/day and then gradually tapered to 40 mg/day after the control of symptoms. As there was severe exacerbation of the symptoms after reduction of the prednisolone dose to

Five days after the second DC pulse, patient developed swelling and severe pain in her left leg. Doppler ultrasonography revealed massive adherent thrombosis in her left external iliac vein extending to the common iliac vein. Various laboratory parameters including the platelet counts were within normal limits. With the development of this complication, thalidomide was discontinued immediately and the patient was managed with subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin 3000 anti-Xa units twice daily for initial seven days and subsequently oral warfarin. The dosage of warfarin was adjusted so as to maintain the International Normalized Ratio (I.N.R.) between 2 to 3. Patient's leg pain and swelling improved considerably and she became symptom free in about a month. She is currently on warfarin 2 mg on alternate days. After seven DC pulses, she is free of her recurrent ENL attacks and we have also been able to bring down her prednisolone dose. At present she is on MB-MDT, cyclophosphamide 50 mg/day and prednisolone 10 mg on alternate days. No other side effects of this regimen have been recorded and patient was doing well in a follow-up of about 9 months.

DISCUSSION

Chronic recurrent ENL is a serious and troublesome complication of leprosy and is often difficult to control. The clinical features of ENL are attributed to increased levels of TNF-α and interferon-γ(11). Thalidomide reverses this phenomenon and also induces reduction in neutrophils, CD4+T cells, TNF-α cells, MHC class-II antigens and ICAM-1 on epidermal keratinocytes and thus effectively controls ENL (11). However its routine use is severely restricted due to its serious toxicities like phocomelia, neuropathies, hyperkalemia and deep vein thrombosis (3, 9).

Acute DVT is a serious and potentially fatal disorder that commonly complicates the course of many diseases in bed ridden patients. It has also been observed that there is unexpectedly higher incidence of DVT when thalidomide is used along with doxorubicin, gemcitabine, 5-Fluorouracil, darbepoietin-α, or dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide therapy (8). Evidently, these observations have been made in patients being treated for metastatic cell carcinoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, or multiple myeloma. To the best of our knowledge no such association has been reported in ENL reactions (when treated with thalidomide alone).

Thalidomide, chemotherapy and glucocorticoids induce apoptosis in tumor cells in vitro and these apoptotic cells might be thrombogenic because of increased activation of tissue factors in the plasma membrane of tumor cells (1). has been shown to inhibit endothelial cell poliferation because of free radical mediated oxidative DNA damage which impairs endothelial cell function (8). It also induces Th-1 cellular response leading to increased secretion of interferon-γ and interleukin-2 (11). Thalidomide is also a potent angiogenesis inhibitor. Thromboembolic events have been reported to occur at a mean of about two months after the start of thalidomide treatment (8). In our patient, DVT developed after eight weeks of starting thalidomide therapy and five weeks of DC pulse therapy.

In such a situation, the question remains that whether the increased risk of DVT is due to thalidomide alone or due to an interaction between thalidomide and other chemotherapeutic agents. Thalidomide, in spite of its limitations, is the drug of choice in severe ENL, and will probably find new usages in future. The clinicians need be vigilant about potential occurrence of thrombotic complications in these patients especially when glucocorticoids or other chemotherapeupic agents are being used concomitantly.

1 Received for publication on 1 April 2004. Accepted for publication on 18 June 2004.

REFERENCES

1. ANDERSON, K. C. Advances in disease biology: therapeutic implications. Semin. Hematol. 38 (2001) 6-10.

2. EISEN, T., BOSHOFF, C., MAK, L, SAPUNAR, F., VAUGHAN, M. M., PYLE, L., JOHNSTON, S. R., AHERN, R., SMITH, I. E., and GORE, M. E. Continuous low dose thalidomide: a phase II study in advanced melanoma, renal cell, ovarian and breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 82 (1990) 812-817.

3. ESCUDIER, B., LASSAU, N., LEBORGNE, S., ANGEVINE, E., and LAPLANCHE, A. Thalidomide and venous thrombosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 136 (2002) 711.

4. FRICK, P. G. Inhibition of conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin by abnormal proteins in multiple myeloma. Ann. J. Clin. Path. 25 (1955) 1263-1273.

5. HEIJBOER, H., BRANDJES, D. P. M., BULLER, H. R., STRUK, A., and TEN CATE, J. W. Deficiencies of coagulation inhibiting and fibrinolytic proteins in out patients with deep vein thrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 323 (1990) 1312-1315.

6. JEW, L. J. Thalidomide in Erythema nodosum leprosum. DICP Ann. Pharmaco. Then 24 (1990) 482-483.

7. MAHAJAN, V. K., SHARMA, N. L., SHARMA, R. C., and SHARMA, A. Pulse dexamethasone oral steroids and azathioprine in the management of erythema nodosum leprosum. Lepr. Rev. 74 (2003) 171-174.

8. MOREIRA, A. L. FRIEDLANDER, D. R., SHIF, B., KAPLAN, G., and ZAGZAG, D. Thalidomide and a thalidomide analogue inhibit endothelial cell poliferation in vitro. 3. Neurooncol. 43 (1999) 109-114.

9. OCHONISKY, S., VERROUST, J., and BASTIYI, G. S. Thalidomide neuropathy incidence and clinico-electro physiologic findings in 42 patients. Arch. Dermatol. 130 (1994) 66-69.

10. PRANDONI, P., LENSING, A. W. A., COGO, A., CUPPINI, S., and VILLALTA, S. The long term clinical course of acute deep vein thrombosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 125(1996) 1-7.

11. SAMPAIO, E. P., KALPAN, G., MIRANDA, A., NERY, J. A., MIGUEL, C. P., VIANA, S. M., and SARNO, E. N. The influence of thalidomide on the clinical and immunologic manifestation of Erythema nodosum leprosum. J. Infect. Dis. 168 (1993) 408-414.

12. SANTOS, A. B., LLAMAS, P., ROMAN, A., PRIETO, E., DE ONA, R., DH VELASCO, J. F., and TOMAS, J. F. Evaluation of thrombophylic states in myeloma patients receiving thalidomide: A reasonable doubt. Br. J. Haematology 122 (2003) 159-160.

13. STEBBING, J., BENSON, C., EISEN, T, PYLH, L., SMALLEY, K., BRIDLE, H., MAK, I., SAPUNAR, F., AHERN, R., and GORE, M. E. The treatment of advanced renal cell cancer with high-dose oral thalidomide. Br. J. Cancer. 85 (2001) 953-958.

14. YASIN, Z., QYUICK, D., and THIAGARAJAN, P. Light chain paraproteins with lupus anti-coagulant activity. Am. J. Hematol. 62 (1999) 99-102.

15. ZANGARI, M., ANAISSIE, E., BARLOGIE, B., BADROS, A., DESIKAN, R., GOPAL, A. V., MORRIS, C., TOOR, A., SIEGEL, E., FINK, L., and TRICOT, G. Increased risk of deep vein thrombosis in patients with multiple myeloma receiving thalidomide and chemotherapy. Blood 98 (2001) 1614-1615.

16. ZANGARI, M., SIEGEL, E., BARLOGIE, B., ANAISSIE, E., SAGHAFIFAR, F., PASSAS, A., MORRIS, C., FINK, L., and TRICOT, G. Thrombogenic activity of doxorubicin in myeloma patients receiving thalidomide-implications for therapy. Blood 100 (2002) 1168-1171.

Nand L. Sharma, Vikas Sharma, Vinay Shanker, Vikram K. Mahajan, and Sandip Sarin2

2 N. L. Sharma, M.D.; V. Sharma, M.D.; A. K. Shanker, M.D.; V. K. Mahajan, M.D.; S. Sarin, M.B.B.S., Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprosy, Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla-171001 India.

Reprint requests to: Dr. N.L. Sharma, Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprosy, Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla- 171001 (H.P.), India. Email: nandlals@hotmail.com

Copyright International Leprosy Association Dec 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved