The use of herbal medications has been steadily increasing. From 1990 to 1997, use of self-prescribed herbal medications increased from 2.5% to 12%, and the percentage of people consulting herbal medicine practitioners increased from 10.2% to 15.1%. (1-4)

Herbal medicines include dietary supplements that contain herbs, either singly or in mixtures. Also called botanicals, herbal medicines are plants or plant parts used for their scent, flavor, and/or therapeutic properties. Since herbal medicines are classified as dietary supplements, there are no Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations regarding accuracy of active ingredients content or efficacy and safety of active ingredients. (2)

Herbal medications can be sold by several marketing companies and can contain varying amounts of active ingredients.

Reasons for the increase in consumer use of herbal medications include:

* perception of efficacy and safety

* non-prescription accessibility

* sense of using a "natural" product

* desperation and dissatisfaction with the use of prescription drugs, and

* lesser cost of herbal medicine. (3)

The U.S. adult population has been steadily increasing as well. The increase in life span has been due in part to better control of infectious diseases, particularly those in early childhood.

The focus of health care in older patients is control of chronic diseases: Older adults typically manifest one chronic disease for each decade past 50. The most common chronic diseases include coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, degenerative arthridites, depression, and cancers. Most chronic diseases are treated with multiple drug therapy. (5) The average older adult takes 5 prescription drugs each day.

The addition of herbal medicines to a program of multiple drug therapy holds the potential for herb-drug interactions. (6,7) The lack of quantitative data on herbal medications, however, makes it difficult to predict the potential for interactions with prescription and over-the-counter drugs.

Drug metabolism

Humans have systems for inactivating and eliminating compounds foreign to the body (xenobiotics). The body identifies prescription drugs and herbal medicines as foreign compounds.

Major sites of drug metabolism are in the liver, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and lung. (5,8-11) The major routes of drug elimination are oxidative metabolism and direct renal excretion of active drugs.

Oxidative metabolism generally makes the drug less active or inactive, typically converting it to a more soluble compound amenable to renal excretion. (10)

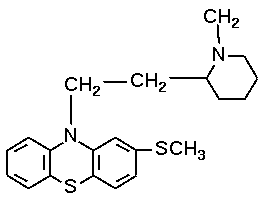

Although there is considerable controversy on the effect of aging on drug metabolism, a consensus supports an age-related decrease in oxidative drug metabolism in older patients. Studies have demonstrated the reduced oxidative metabolism of amitriptyline, diazepam, imipramine, and thioridazine in older subjects. However, it is clear that the decrease in drug metabolism is selective. (5,10,12,13)

The enzymes catalyzing oxidative drug metabolism are relatively specific for drugs; these include CYP 1A2, 2D6, 2C9, 2C19, 3A4, and p-glycoprotein. (5,10,13) The enzymes can be increased via de novo synthesis by exposure to certain drugs, chemicals, and herbal medications. This enzyme induction causes an increased rate of metabolism of drugs and decreases the availability of the parent drug. (5,10)

Some xenobiotics can induce the metabolism of other compounds as well as their own (eg, phenobarbital, phenytoin). Inducing compounds are usually specific for a specific drug metabolizing enzyme family (carbamazepine induces CYP2C8/9/10; sertraline induces CYP2C18/19; phenytoin induces CYP3A4). Diverse chemicals may induce the same drug-metabolizing enzyme, for example, glucocorticoids and anticonvulsants both induce CYP2E1.

Inhibition of drug-metabolizing enzymes causes increased levels of parent drug, prolonged drug effects, and increased drug toxicity. Competition for the active site of drug-metabolizing enzymes or by two or more drugs can result in decreased inactivation of one of the drugs and an increase and prolongation of drug effect, ie, toxicity.

Although many widely used herbal medications have been tested for efficacy in controlled random placebo based trials, many more have not undergone such testing. (3,6,7)

The seven herbal medicines most sold in the United States are (14)

1. Ginkgo biloba

2. St. John's Wort

3. Ginseng

4. Kava

5. Saw Palmetto

6. Garlic

7. Echinacea.

Efficacy information and drug interaction data is available for the first five. (14) Efficacy claims for garlic and echinacea are not supported in the literature. (1,2,6) This article will discuss specific proven efficacies and, where known, the mechanisms of action for Ginkgo biloba. Subsequent articles will discuss the other 4 herbals noted above. Documented drug-herb interactions will be presented.

Ginkgo biloba

Ginkgo biloba is known for its antioxidant and neuroprotective effects. The herb has a wide variety of claims for efficacy, (1,2,6,7) including some degree of efficacy for the treatment of dementias, decreased memory, cerebral insufficiency, anxiety/stress, tinnitus, asthma, Raynaud's disease, and intermittent claudication, and when used in combination with aspirin, for treating thrombosis. (6,15-17)

Pharmacological actions. The preparations used in clinical practice have been standardized in regard to ginkgo flavones (24%) and terpene lactones (6%), which are thought to be the active ingredients. The flavonoids act as free radical scavengers and the terpenes (ginkgolides) inhibit platelet-activating factors and facilitate blood flow. Effects of these actions may:

* reduce allergic reaction and inflammation (eg, asthma and bronchospasm)

* treat circulatory diseases, Alzheimer's disease, cancer, Parkinson's disease, and rheumatoid arthritis

* alleviate hypoxia, seizure activity, and peripheral nerve damage

* reduce functional and morphological retina impairments

* reduce fibrosis development

* relax penile tissue in vitro (efficacious in treating impotence)

* manage peripheral vascular disorders such as Raynaud's disease, acrocyanosis, and post-phlebitis syndrome. (14)

In one trial that enrolled patients with hearing disorders secondary to vascular insufficiency in the ear, approximately 40% of those treated orally with a leaf extract for 2 to 6 months showed improvement in auditory measurements, and effectiveness was shown in relieving vertigo. (14)

In older men with slight age-related memory loss, ginkgo supplementation reduced the time required to process visual information. (14)

Overall, results of studies of ginkgo for memory improvement, dementia, have been inconclusive. (5) Dosage and administration. Standardized ginkgo leaf extracts such as Egb76, 120 to 720 mg/d, have been used in clinical trials for dementia, memory, and circulatory disorders. A common dose is 80 mg/d to 240 mg/d of 50:1 standardized leaf extract, divided into 2 or 3 daily doses, by mouth. (14)

Adverse effects/toxicology. Severe side effects are rare; documented effects include headache, dizziness, short-term memory loss, vigilance, heart palpitations, and GI and dermatologic reactions. Ginkgo pollen can be strongly allergenic. (14)

Fifty ginkgo biloba seeds can induce tonic/clonic seizures and loss of consciousness. Seventy reports have shown 27% lethality (attributed only to ginkgotoxin found in the seeds).

Ingestion of ginkgo in one report was associated with spontaneous bilateral subdural hematomas. (14) Reported drug interactions are detailed in the Table.

Conclusion

Physicians are reminded to ask their patients about any herbal and dietary supplements that they might be taking. It might help to have patients fill out a chart to keep on file that lists this information, including the frequency and reasons for using supplements. Refer to the chart on page 38.

References

(1.) Ang-Lee MK, Moss MK, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA 2001; 286(2):208-16.

(2.) Ernst E, Pittler MH. Herbal medicine. Med Clin North Am 2002; 86(1):149-61.

(3.) Astin, JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: Results of a national study. JAMA 1998: 279(19):1548-53.

(4.) Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med 1993; 328(4)246-52.

(5.) Bressler R, Bahl JJ. Principles of drug therapy for the elderly patient. Mayo Clin Proc 2003: 78(12):1564-77.

(6.) Ernst, Edzard. The risk-benefit profile of commonly used herbal therapies: Gingko, St. John's Wort, Ginseng, Echinacea, Saw Palmetto, and Kava. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136(1):42-53.

(7.) Miller LG. Herbal medicinals: Selected clinical considerations focusing on known or potential drug-herb interactions. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158(20):2200-11.

(8.) Schmucker DL. Liver function and phase I drug metabolism in the elderly: a paradox. Drugs and aging 2001; 18(11):837-51.

(9.) Klotz U. Effect of age on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1998; 36(11):581-5.

(10.) Wilkinson GW. Pharmacokinetics: The dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, and elimination. In Goodman AG, consulting ed; Hardman JG, Limbird LE, eds-in-chief. Goodman and Gilman: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Co.; 2001:3-29.

(11.) Okey AB. Enzyme induction in the cytochrome P450 system. Pharmacol Ther 1990; 45(2):241-98.

(12.) Rowe JW, Andres R, Tobin JD, Norris AH, Shock NW. The effect of age on creatinine clearance in men: a cross- sectional and longitudinal study. J Gerontol 1976; 31(2):155-63.

(13.) Cozza KL, Armstrong SC, Oesterheld JR, eds. Concise Guide to Drug Interaction Principles for Medical Practice. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing;2003:11-40.

(14.) David S. Tatro, ed. Drug Interaction Facts: Herbal Supplements and Food. Saint Louis, MO; Facts and Comparisons, A. Walters Kluwer Company; 2004. Also available online at: www.factsandcomparisons.com.

(15.) Kleijnan J, Knipschild P. Ginkgo biloba for cerebral insufficiency. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 34(4):352-8.

(16.) Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA. The efficacy of Ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1998; 55(11):1409-15.

(17.) Pittler MH, Ernst E. Ginkgo biloba extract for the treatment of intermittent claudication: a met-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med 2000; 108(4):276-81.

Dr. Bressler is professor of medicine and pharmacology, University of Arizona Health Sciences Center and the Sarver Heart Center, Tucson, and serves on the Geriatrics Editorial Advisory Board.

Disclosure Dr. Bressler's works are supported by the Sarver Heart Center and the Brach Foundation.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Advanstar Communications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group