"I don't have to live in my car anymore."

It is through my personal and professional experience that I write this article on empowerment. I have thought about empowerment a lot throughout the years. I have researched it, lived with it and lived without it. I have shared empowerment with others. Without it, I have been utterly alone. Empowerment is simple, yet complex. It pertains to people with psychiatric disabilities and to people with any disability. I learned this through working at a center for independent living. People with disabilities face many obstacles that can be disempowering. It is evident that when the disability community unites and rallies behind a cause, we become more empowered citizens.

I am writing this for the individuals, and for people who know individuals, who feel disempowered and alone. I hope that presenting some of the ingredients necessary for empowerment will facilitate self-directed growth and freedom.

I am the director and systems advocate for the Mental Health PEER Connection (MHPC), a member of the Western New York (WNY) Independent Living Project, Inc., family of agencies located in Buffalo, New York. MHPC is a peer-driven advocacy organization dedicated to facilitating self-directed growth, wellness and choice through genuine peer mentoring. MHPC employs 21 fulltime employees who have a mental illness or have recovered from a mental illness. Our peers are located in the state hospital, the county hospital, the county jail, the public mental health system and in vocational programs. We represent fellow mental health consumers by performing individual and systems advocacy to increase the rights, freedom and independence of those with mental health disabilities. We advocate with mental health housing providers, the Social Security Administration (SSA), state and local legislatures, the New York State Department of Vocational and Education Services for Individuals with Disabilities (VESID), public mental health providers in Erie County, the Erie County Department of

Mental Health, the Erie County Department of Social Services and the City of Buffalo Mental Health Court and Family Court. We conduct several self-help and mutual support groups weekly. In 2002, we provided independent living skills training, housing assistance, benefits advisement, advocacy and mobility training to over 350 individuals with psychiatric disabilities. We work with mental health housing providers and the county mental health department via the Community Services Board and advocate for people who are being mandated into treatment under the Involuntary Outpatient Commitment Law in the state of New York.

As the systems advocate, I have guided our center in advocating for what our consumers want by holding several town meetings on consumer issues. This information is disseminated to various stakeholders via position papers. Based on the information gathered at these town meetings, our agency has sponsored a freedom march, informational pickets, parity picnics and legislative breakfasts. We have demonstrated for greater freedom. We held letter-writing campaigns, call-ins, speak-outs, community open houses, a self-help luncheon and a managed care educational campaign. We helped to implement the Consumer Advisory Council in the Buffalo Psychiatric Center, the Erie County Medical Center Psychiatric Department, Gold Choice Family Medicine (a managed care health insurance for people with psychiatric disabilities) and a human service survey that "pokes a hole in West Side neighborhood group arguments that the community is over saturated with social service organizations" (Tan, 2000).

We have directed over $70,000 for peer services to improve the quality of life of Erie County, New York, mental health recipients. Through MHPC's efforts, many people with mental health disabilities in Erie County have improved their living standard. In addition, I serve as the co-chair of the Erie County Anti-Stigma Task Force.

In 1990, I came to the WNY Independent Living Project for help. I was living out of my car in the streets of Buffalo. I feared everyone due to my mental illness--multiple personality disorder (MPD). When I told the independent living counselor this, she did not look down on me and she did not seem to judge me. She expressed concern that I was living on the streets and that I feared that someone was going to kill me for no logical reason. She told me about housing that was available and convinced me to stay with a friend until the housing was arranged. She seemed to care. I listened. She showed me respect. She told me of other services that were available to me because I had a disability. She said that she knew this because she had a disability too. I did not understand it all. But she said that it was OK and that I could come back if I needed any other information or assistance. She gave me something that I had lost a long time ago. It was something that I never thought I would have again. She gave me hope.

I was severely abused as a child. I developed personalities to deal with it. I could not run away physically, so I ran away in my head. The personalities protected me from the abuse. As an adult, I was no longer being abused. But I still had the personalities--over 280 of them. I did not know that I had these personalities until I was 25 years old, when I was diagnosed with MPD while in a psychiatric hospital. Often, I was suicidal. I never knew why. I went to psychiatric hospitals for help. I have been in psychiatric facilities on 12 different occasions, for months at a time. The more I went, the more I realized that they were not helping me. I felt increasingly disempowered. The hospital staff members were getting frustrated with me as well. At one point, I was on 13 different types of psychotropic medications: anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, anti-anxiety, anti-everything. Eventually, I was on medications to counteract the medications. I was constantly looking outside of myself for something to fix me: the hospital, the doctor, the pill or the therapy.

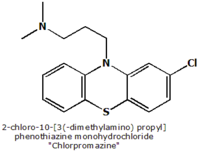

Then the most disempowering thing happened to me, changing my life. Ironically, it led to my becoming empowered. Many people with disabilities are driven into the disability rights movement due to their own disempowering experiences. This was true for me. I was hospitalized for the eleventh time. I was suicidal and a danger to myself and to others. I did not care if I lived or died. I was receiving disability benefits. I was not in contact with my family and had no support network. I was utterly alone. The hospital "recommended" electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). This is when they shock the brain to help a person overcome depression. As a trauma survivor, this idea terrified me. The hospital staff developed a treatment plan without my participation. The plan consisted entirely of me making a decision to get ECT. In front of a room filled with hospital staff, I was asked to sign the treatment plan. I signed the plan, but I was terrified. I wanted to leave the hospital because it was clear that they wanted to electrocute me. Most psychiatric hospitals are locked down. This hospital was no exception. They would not let me leave, so I tried to escape twice. The first time, I jumped through a nurses' station window. The second time, I pushed a doctor out of the way as she entered the ward. Each time, I was "taken down," shot up with Thorazine and put in restraints in a seclusion room. I could not scratch my nose or go to the bathroom without help. This was the most disempowering time in my life. I could not really figure out how I had gotten to this point, but I had. I had no control over my life. I had no decision-making power. I did not understand that I had rights. I felt totally alone. This was the turning point in my life. I decided that I was sick of this and that I was not going to take it anymore. I begged the hospital staff to let me out of the restraints. I promised them that I would not try to escape again. I pretended I was happy. I said that I did not feel suicidal anymore. I thanked them for helping me to not hurt myself by trying to escape. I said I was ready to start my life again. So they let me out. I was finally free.

But I was not better. I held onto the hope that I found at the WNY Independent Living Project. But that was all I had. I wanted to get better and I was ready to do what it took to get better. My outpatient counselor told me about a hospital in Texas that treated trauma survivors, especially those with MPD. I was hesitant to go to another hospital, but I wanted to get better. I took the risk and went to Texas in 1994. This hospital was like no other. They accepted Medicare. During previous hospitalizations, the only activity was taking medication. It was very boring. But this hospital was very different. I saw a psychologist for one hour, five times per week. My personalities worked out their issues during these sessions. I attended group therapy, clay therapy, anger therapy, occupational therapy, cognitive therapy and art therapy. I saw a psychiatrist every day. I got better. I was with people just like me. There was camaraderie. We sang songs of hope. We had privileges to go outside.

I left with the desire for a new beginning. I returned to Buffalo with the ambition to begin my life. Later that year, I saw a brochure for an advocacy and empowerment training event for people with psychiatric disabilities sponsored by the WNY Independent Living Project. I signed up and attended. I was scared. I did not know what to expect. But it was great. The presenters spoke of their psychiatric disabilities and hospitalizations and their current role as advocates. They talked about empowerment. It was like they lit a fire beneath me. I was not alone. So many people with psychiatric disabilities were fighting for their rights. They had lost their rights, as I had. I did not know that others had gone through it as well. As I looked at the presenters, another idea popped into my head. If they could get paid to advocate, I could do it too. I applied for a job as a peer advocate at the WNY Independent Living Project and began employment in 1995.

To this day, my hospitalizations have ended. The advocacy and empowerment training opened my eyes to the disempowering care systems for people with psychiatric disabilities. And the WNY Independent Living Project opened my eyes to the many disempowering systems serving the disability community. I began to understand that the whole disability community is a civil rights movement. I saw this on many levels: through my own experience, through my employees' experiences, through our consumers' experiences and through the communities' attitudinal barriers.

Empowerment must begin with the individual and then expand to the community as a whole. I have witnessed many subtle (and not so subtle) actions that take power away from the disabled individual. However, it is apparent that the Erie County Department of Mental Health is trying to shift the pendulum of power from the professional mental healthcare provider to the consumer of services. The power of the psychiatrically disabled individual is in the hands of the individual, with one exception: When the individual is a danger to himself (or herself) or others, that person may lose his right to choose, his right to freedom and his right to decide what treatment is best for himself.

I met Judi Chamberlin at the 2001 National Association for Rights Protection and Advocacy (NARPA) Conference held in Niagara Falls, New York. I was very impressed by her insights on empowerment for psychiatric survivors. Her article A Working Definition of Empowerment (1999) is enlightening. She gathered a dozen leading American consumer/ survivor self-help practitioners to form the advisory board of the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Its first task was to define empowerment for psychiatric survivors, which it did as follows:

1. Having decision-making power.

2. Having access to information and resources.

3. Having a range of options from which to make choices (not just yes/no, either/or).

4. Assertiveness.

5. A feeling that the individual can make a difference (being hopeful).

6. Learning to think critically, unlearning the conditioning, seeing things differently (e.g., learning to redefine who we are [speaking in our own voice]; learning to redefine what we can do; and learning to redefine our relationship to institutionalized power).

7. Learning about and expressing anger.

8. Not feeling alone, feeling part of a group.

9. Understanding that people have rights.

10. Effecting change in one's life and one's community.

11. Learning skills (e.g., communication) that the individual defines as important.

12. Changing others' perceptions of one's competency and capacity to act.

13. Coming "out of the closet."

14. Growth that is never ending and self-initiated.

15. Increasing one's positive self-image and overcoming stigma (Chamberlin, 1999).

I believe that these characteristics are necessary for one to become empowered. Often, these aspects are overlooked in government systems, health care systems and the rehabilitation system. I see this as a person who has used the system since the 1980s, as an employer of 21 full-time staff with psychiatric disabilities and as a systems advocate for people with psychiatric disabilities in my county. It is my experience that these systems of care are not consciously aware of the fact that they are disempowering. They are trying to help individuals, their intentions are good, but the results of their policies, rules and regulations can be devastating. This is due to misunderstanding, numerous waiting lists, piles of paperwork requirements and budget cuts. The person with a disability gets left out of the picture when, in fact, he or she is supposed to be the center of the picture. That is why the 400 independent living centers throughout the United States work so well. People with disabilities have "been there." Often, a person needs a road map to navigate these care systems. Independent living centers have the road maps and they have gone the distance.

Having decision-making power. This is key for the person with a disability. Often, systems of care make decisions about what is best for the person with a disability without even talking to the person. Often, our society does not allow the person with a disability to make decisions. Once, I was helping an individual who was deaf to find an apartment. The landlord decided that the individual would not like living in his building. Taking away the decision-making power can be subtle, as well. While I was having dinner with a friend who uses a wheelchair, the waitress asked me what he wanted for dinner. Government systems of care take away decision-making power as well. While on disability, I applied to VESID for services. My goal was to become a chef. They told me I was unemployable. It was a good thing that I did not listen to them!

Having access to information and resources. There is so much information available for people with disabilities that it is hard to access all of it. The opposite is true as well. Many people with disabilities live in utter poverty and isolation. They have no access to information. For example, the Erie County Behavioral Health Vocational Task Force Final Report states that:

Thus, many people with psychiatric disabilities fear returning to work or going to work for the first time because they fear losing their benefits (M. Weiner, Erie County Commissioner of Mental Health, personal communication, March 6, 2003). On a more human rights level, many people with disabilities who live in institutions lack the information they need regarding their rights in that institution, such as those stated in advanced directives, the Olmstead Decision, etc. As a systems advocate in Erie County, I have heard many psychiatric survivors talk about being institutionalized. They did not know their rights because when they were given the sheet of paper with their rights on it, the paper was thrown into a secured locker with all their personal belongings.

SSA causes difficulty in accessing information and resources as well. When I returned to work after being on Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), I knew that I had a nine-month trial work period; but I was not sure when the trial period started and when it stopped. I just kept receiving checks. Then, I received a letter from SSA that stated that they overpaid me by $10,080. They asked that I return the overpayment by a certain date. That letter almost sent me back into the hospital.

Having a range of options from which to make choices (not just yes/no, either/or). Most adults in life make informed decisions by weighing the consequences of their choices. Why can't people with disabilities have that right as well? When I was homeless, I had to decide to spend my disability check on either medicine or food. When I was in the psychiatric hospital, I was given no option other than ECT. Many housing providers offer housing under the condition that the person with the disability continues to take his (or her) medication or he will be kicked out. In Buffalo, the winters can be very cold, and medications can have serious side effects. I believe that there is always room to work things out, to find out what people with disabilities want and to discover what their hopes, dreams and aspirations are. It is not necessary to threaten to take them away if they do not cooperate. There is no need to manipulate. It is better to contribute to the conspiracy of hope, to problem solve and negotiate, to obtain a win/win solution.

Assertiveness. Standing up for one's rights without fear of retribution is a very empowering act for a person with a disability. When necessary, people with disabilities must depend on others. When people with disabilities think for themselves, it is a wonderful process. Many have lived their lives with caretakers who have made decisions and plans without asking for input from the person with a disability. When that person becomes assertive and determines what he or she wants, new freedom exists. Many care providers do not understand this. In the mental health system, when people with psychiatric disabilities assert themselves, they are often called "non-compliant." It is important to discuss with the person with the disability what he (or she) wants and to understand why he wants it. Communication is key. There are many good reasons why a person with a disability does not want to follow a certain plan, especially when the plan was developed without the involvement and consent of that person.

Feeling that the individual can make a difference (being hopeful). When I was on disability, I was ashamed of not contributing to society. I was ashamed to socialize with others, in fear that they would ask me what I was doing for a living. I was embarrassed at the supermarket when I used food stamps to pay for my groceries. I felt totally useless. When I started working at the Independent Living Project, I began to feel like I was making a difference. People with disabilities do not want to be a burden, no matter how moderate or severe the disability; but often others see the individual with disability as a burden. All disabled individuals have something to offer, can make a difference in someone's life (if not many lives) and can be contributing members of society.

Learning to think critically, unlearning the conditioning, seeing things differently (e.g., learning to redefine who we are [speaking in our own voice]; learning to redefine what we can do; learning to redefine our relationship to institutionalized power). Often, people with disabilities and the people who work with individuals with disabilities only see the disability, not the person. For years, I saw myself as a "multiple," not as anything else. And that kept me down. I saw no recovery. I saw no life outside of therapy. I had no natural supports. My supports were based on group and individual therapy. I had no passion and no desires. When I became an advocate, I began to see myself as something other than my disability. In Erie County, the Department of Mental Health encourages representation of people with psychiatric disabilities in the planning and implementation of services for people with mental health issues. I have been attending such planning meetings since 1995. At first I was very intimidated to be in a planning meeting with professionals and non-disabled individuals. But, over the years, I have noticed that they have their quirks too. I have as much right to say what needs to be said as they do. I noticed that they did not view me as a mental case but as a person with insight and experience regarding what people with psychiatric disabilities want.

Learning about and expressing anger. I have learned that anger is a healthy and natural emotion. People with disabilities have many things to be angry about: Americans with Disabilities Act violations, reduced health insurance coverage for durable medical equipment or personal care attendants, no state health insurance parity legislation, housing discrimination, stigma, and all of the personal issues that people in general get angry about. When a person with a disability gets angry, some find this unacceptable. I remember getting angry in a hospital because a nurse would not give me a nighttime medication so I could go to sleep. I lost my privileges for three days. Some people with disabilities have been institutionalized all their lives or lived in sheltered environments. Some were never taught appropriate ways to express angry feelings. This built-up anger and explosive energy sometimes results in their institutionalization in a psychiatric hospital (for evaluation) or jail. It is important to remember that people with disabilities have feelings too, and one of those feelings is anger. They should be taught appropriate ways to express it.

I think that "Not feeling alone, feeling part of a group" is one of the most important qualities of empowerment that Chamberlin cites. Many individuals with disabilities are isolated through living alone, in special housing, with family or in institutions such as psychiatric hospitals or nursing homes. Institutionalized people are often separated from each other by a door or wall, which allows for little contact with the outside world. I remember living in a one-room apartment while I was receiving SSDI benefits. I spent my days going to therapy. I felt totally alone. I did not know that there were others just like me. It is very important to network with other people. The Independent Living Project provides opportunities for this on a continuous basis: first, by constantly updating the mailing list and asking everyone served if they want to be on the mailing list; and second, by mailing notices of self-help groups, workshops, town meetings, special events, action alerts, etc. During events and presentations, I introduce myself by saying a little bit about my past, and then the group participants talk about issues that concern them. Friendships are formed, support is developed and that feeling of loneliness disappears.

Understanding that people have rights. MHPC has an educational program on mental health recipients' rights. It is amazing to see how many people with psychiatric disabilities do not know about their rights. This is most clearly seen regarding housing rights in our county. Many people with psychiatric disabilities do not realize that they can leave their current housing. However, if they do leave, their standard of housing would decrease dramatically. New York State has a law called the Involuntary Outpatient Commitment Law, or Kendra's Law, which can force non-compliant mental health consumers into outpatient treatment if they have had many recent hospitalizations or incarcerations and are deemed unable to survive in the community by themselves. Erie County has successfully avoided taking people to court by encouraging the recipient to agree to the program. Recipients are put into the "Diversion Program," which provides increased case management services. Basically, it is the same program recipients would get if they went to court but without the legal representation. MHPC is concerned that some of these people are forfeiting their rights and may not meet the criteria because they do not have proper legal representation. Because we have found that many mental health consumers do not know their rights, we developed a workbook, we go to places where mental health consumers congregate and we provide education on their rights.

We also have rights regarding our vocational and rehabilitation goals. VESID assists those with disabilities in becoming more productive members of society. However, VESID has limitations and budgetary restraints. When they told me I was unemployable, I did not know that I had the right to seek help from the Client Assistance Program (CAP).

Effecting change in one's life and one's community is another quality for empowerment. In past years, many disabled people simply existed; they were warehoused and overly medicated, with no expectations of recovery or improvement. As the disability rights movement grew, more people with disabilities demanded more out of life than medication and maintenance. They had goals, aspirations and dreams. They wanted to change and improve their lives. As people with disabilities accomplish these goals and continue to effect change, their communities change slowly. When people in my life expected change in me, I did change. But if the expectation was not there, I did not change. Because of the changes in my life, I am effectively altering the community in which I live today. I am affecting understanding and attitudes toward people with mental illness in Erie County, New York.

Chamberlin includes learning skills (e.g., communication) that the individual defines as important. It is crucial to communicate with the person who is disabled to find out what skills the individual wants to learn and what help he or she wants. During one hospitalization, I was painting a stained plastic window (they did not allow glass). I put the window away and moved to another part of the ward. I did not paint the item well, but I tried. When I returned to the room, a nurse was painting my window. I said, "What are you doing? That's mine." She said, "I was just helping." I did not want her help. I wanted to learn it myself. But, she did not communicate with me. At the Independent Living Project, I have learned that we do not do for others what they can do for themselves, unless they ask. It is crucial not to assume what the individual wants to learn. It is important to know what the individual's goals are and how he or she wants to achieve them.

Changing others' perceptions of one's competency and capacity to act is a quality that Chamberlin cites. I believe this is directed to ward the people working with the person with a disability. Just because I acted irrationally or de-compensated last week does not mean that I am always that way. Those of us with disabilities want to be judged on our abilities today, on our record and on our integrity, not on our weakest moment. Like all people, we change, grow and learn from our experiences.

Coming out of the closet. I think this quality pertains exclusively to people with hidden disabilities, such as people with mental disabilities. The surgeon general reports that one in five Americans is affected by mental illness during his or her lifetime. Many people are ashamed to have a mental illness and fear the discrimination and stigma that occurs regularly. But as more people share their disabilities, the more commonplace it will become. The more people talk about it, the more acceptable it becomes. The more acceptable it becomes, the more people will get help. This may result in fewer deaths by suicide each year.

Growth that is never ending and self-initiated is cited by Chamberlin as an empowering quality. People with disabilities should have the same rights as any other person to pursue their dreams to the fullest extent possible. As providers of services to people with disabilities, we should be facilitators of such dreams and potential.

Increasing one's positive self-image and overcoming stigma. This is Chamberlin's final quality of empowerment. Throughout Erie County, people with mental illness suffer from stigma that they have internalized, and by internalizing they affect their self-image and self-esteem. They become the disability. This is often exhibited in their vigilance about confidentiality--about anyone finding out that they might have a mental illness. There are many good social and internal reasons for this. I have dealt with parents who lost their children in custody battles with their spouses because the judge found out that they have a mental illness. People with mental illness have lost their jobs because they spent time in a psychiatric hospitals. In our region, there is a shelter for battered women, but they will not accept women with mental illness. The shelter managers say that they do not have the staff to deal with this issue. But if everyone who has a mental illness spoke out, maybe, just maybe, discrimination would decrease. As part of the Erie County Anti-Stigma Task Force, we launched an advertising campaign with the following message: "Mental Illness Is Treatable, Treat It That Way." We must overcome stigma in order to improve the cultural and civil rights barriers that the disabled community in America faces today.

What has been my most empowering experience so far? In December 2000, I purchased a house in the suburbs of Buffalo. It is my first house. Ten years ago, I was homeless. I became a bona fide homeowner with all the rights and responsibilities that come with it. In spring 2001, I had a barbeque for the entire MHPC staff at my house. If I can do this, so can others. That is what empowerment is all about: achieving goals and sharing them with others.

REFERENCES

Tan, S. (2000, August 22). Human services survey finds support. The Buffalo News, City & Region Section, p. 1.

Chamberlin, J. (1999). A working definition of empowerment. Retrieved May 28, 2003, from http://www.power2u.org/bobby/empower/working_def.html.

Erie County Department of Mental Health. (2003, March). Erie County Behavioral Health Vocational Task Force Final Report. Retrieved May 27, 2003, from http://www.erie.gov/health/mentalhealth/ BehavHlthTFVocSummaryReport.pdf

COPYRIGHT 2004 U.S. Rehabilitation Services Administration

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group