Objective: Increased central nervous system norepinephrine outflow and α^sub 1^-adrenergic receptor responsiveness appear to be involved in the pathophysiologic processes of trauma-related nightmares in post-traumatic stress disorder. On the basis of reports that the brain-accessible α^sub 1^-adrenergic antagonist Prazosin substantially reduced chronic combat-related nightmares among Vietnam War veterans, we evaluated Prazosin effects on combat-related nightmares among combat soldiers returning from Operation Iraqi Freedom. Methods: Twenty-eight soldiers who self-reported distressing combat traumarelated nightmares on a postdeployment questionnaire were prescribed low-dose Prazosin before bedtime. Results: Of the 23 soldiers for whom follow-up evaluations were available, 20 experienced marked improvement (complete elimination of nightmares), 2 experienced moderate improvement (reduced nightmare frequency or intensity), and 1 experienced no change. Prazosin was well tolerated. Conclusions: Prazosin appeared highly beneficial for combat-related nightmares characteristic of post-traumatic stress disorder among troops recently returned from Operation Iraqi Freedom. These findings provide a rationale for a placebo-controlled trial to establish efficacy in this population.

Introduction

Recurrent combat-related nightmares are a central feature of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among military combat veterans and often persist for many decades after the traumatic events.1 Unfortunately, these distressing combat-related nightmares and associated sleep disruptions often are resistant to pharmacologie treatment.2 For example, the only drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for PTSD, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors sertraline and paroxetine, often are not helpful for these nighttime PTSD symptoms.3 In fact, studies among veterans suggest that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are less effective in general for combat trauma-related PTSD than for PTSD secondary to civilian life trauma.4,5 Therefore, it is important to find new pharmacologic approaches to these distressing nighttime PTSD symptoms. Understanding the pathophysiologic features of PTSD should facilitate this search.

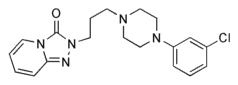

Accumulating evidence from clinical and preclinical studies supports the involvement of increased central nervous system (CNS) adrenergic activity in the pathophysiologic development of PTSD and of trauma-related nightmares and sleep disruption specifically. This increased CNS adrenergic activity in PTSD appears to involve both increased norepinephrine outflow6 and increased postsynaptic adrenergic receptor responsiveness to norepinephrine.7 Increased CNS adrenergic activity among veterans is particularly prominent at night,8 and stimulation of brain postsynaptic α^sub 1^ -adrenergic receptors disrupts sleep physiologic processes.9,10 Taken together, these findings suggest that a drug that blocks CNS aradrenergic receptors at clinically administered doses could be effective for treatment of nightmares and sleep disturbance in PTSD. The α^sub 1^-adrenergic antagonist Prazosin is such a drug. Introduced as the antihypertensive drug Minipress in the 1970s, it is now available as an inexpensive generic drug. Prazosin is the only aradrenergic antagonist clinically available that is substantially lipid soluble and is thus able to easily cross the blood-brain barrier.11 It has been demonstrated to block functional responses to stimulation of brain a α^sub 1^ -adrenergic receptors with peripherally administered doses in the clinical range.12

The Madigan Army Medical Center (MAMC) Behavioral Health Clinic (BHC) has encountered a substantial number of returning combat veterans from Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) presenting with recurrent, distressing, combat-related nightmares and associated sleep disturbances typical of PTSD. On the basis of reports that Prazosin markedly reduced chronic trauma-related nightmares and improved sleep among Vietnam War combat veterans with PTSD,13,14 MAMC psychiatrists began prescribing Prazosin for combat-related nightmares among OIF combat veterans. This report describes encouraging responses to Prazosin among these soldiers.

Methods

We reviewed MAMC pharmacy and BHC records for all patients who were OIF veterans and who were prescribed Prazosin for combat-related nightmares from May 2003 (when OIF veterans began presenting for care in the MAMC BHC) through December 2003. Twenty-eight soldiers (27 men and 1 woman, 20-41 years of age) had endorsed distressing, combat-related nightmares on a routine, postdeployment, mental health screening questionnaire. After being evaluated in the BHC, they began to receive Prazosin. Only two patients reported previous psychiatric and/or substance abuse disorders. Ten patients were receiving no psychotropic medications before or during the Prazosin trial. Eighteen patients presented to the BHC with persistent nightmares despite one or more of a variety of maintenance psychotropic drugs prescribed either in Iraq or by another MAMC clinician. These included eight patients previously prescribed trazodone for sleep, one patient prescribed zolpidem for sleep, and nine others prescribed a variety of medications for depressive and/or anxiety symptoms (including paroxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, venlafaxine, bupropion, mirtazapine, and amitriptyline).

Treatment emphasis was on stress symptom reduction and enhancement of ability to continue military duty performance. This approach is consistent with principals of "combat stress control" directed at normalization of stress disorder symptoms. Therefore, target symptom identification was emphasized and a formal diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder was generally avoided. This approach also respected soldiers' frequent concerns that a formal psychiatric disorder diagnosis might compromise future success in their military careers. However, combat-related nightmares and sleep disruptions in most cases were clearly accompanied by other symptoms that, taken together, fulfilled Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, diagnostic criteria for PTSD.

Low-dose Prazosin therapy was begun at 1 mg before bedtime. Patients generally were monitored weekly. If nightmares persisted, then the Prazosin dose was increased in increments of 1 mg per week. The highest dose associated with nightmare reduction was 5 mg at bedtime. Records were reviewed for demographic information, combat history, presenting complaints, concomitant psychotropic medications, and any psychiatric history. Responses with respect to combat trauma-related nightmares were rated with the Clinical Global Impression of Change.15 This 7-point scale ranges from markedly improved to markedly worse. Marked improvement was defined operationally as complete resolution of nightmares. Moderate improvement was defined as a subjectively meaningful reduction in nightmare frequency and/or intensity.

Long-term (>3-month) psychiatric follow-up monitoring was rarely possible for these patients. Many of the soldiers who were treated were Reserve or National Guard soldiers processed through MAMS, who then returned to their home units.

Results

Of the 28 patients prescribed Prazosin, the effects of Prazosin could not be assessed for 5 because of an absence of follow-up evaluation or incomplete medical records. Of the remaining 23 patients, 20 were rated on the Clinical Global Impression of Change as markedly improved, 2 as moderately improved, and 1 as unchanged (even after Prazosin dose increases of 1 mg in weekly increments had achieved a total dose of 6 mg at bedtime). Sixteen patients' nightmares were markedly or moderately improved with only 1 mg at night. However, one patient required 5 mg at night before his nightmares resolved. Three representative cases are presented to illustrate the types of combat trauma encountered, the major presenting symptoms, and the responses to Prazosin.

Case 1

A 37-year-old National Guardsman originally presented to the BHC complaining of recurrent distressing nightmares related to a combat event that had occurred 4 months earlier, in which the patient killed an enemy at close range. When the patient was screened for the presence of additional psychiatric symptoms, he reported insomnia and low energy. However, he identified these additional symptoms as being primarily caused by his nightmares. Prazosin (1 mg at bedtime) therapy was initiated for the treatment of nightmares. No other psychotropic medications were started.

The patient was seen for follow-up evaluation 2 weeks later. At that time, he reported complete resolution of the nightmares. Therefore, no increase in the Prazosin dose was required. The follow-up evaluation 1 month later revealed continued remission of nightmares and improved sleep.

Case 2

A 20-year-old Army Reservist was wounded in action in May 2003 with a disabling leg injury when his vehicle was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. The patient presented to the BHC in November 2003 with a complaint of recurrent nightmares of the explosion, which repeatedly awakened him in a "cold sweat" throughout the night. The patient also reported severe sleep disturbances and troublesome daytime irritability. He attributed these associated symptoms to his recurrent nightmares. His symptoms were consistent with PTSD. Prazosin (1 mg at bedtime) therapy was initiated to treat his recurrent nightmares. The patient was receiving no other medications.

The patient was seen for follow-up evaluation 5 days later, at which time he reported having a marked reduction in the frequency and intensity of his nightmares and noted substantial improvement in his sleep. No increase in the Prazosin dose was made. The patient was seen again after 2 weeks, at which time he noted complete resolution of his nightmares.

Case 3

A 20-year-old regular Army soldier was wounded in action in Iraq when the vehicle he was driving was hit with an improvised explosive device. He sustained upper extremity burns while rescuing fellow soldiers from the burning wreckage. When evaluated 8 weeks later, the soldier reported recurring, sleep-disrupting nightmares of the event. When screened for additional psychiatric symptoms, he particularly noted having a phobic avoidance of military vehicles, which made him very anxious and distraught. He also noted hypervigilance, particularly while driving. These major presenting symptoms were consistent with PTSD. Prazosin (1 mg at bedtime) therapy was initiated for the treatment of the nightmares. No other psychotropic medications were initiated.

The patient was seen weekly for follow-up evaluation. After 2 weeks of Prazosin therapy, the patient reported resolution of his nightmares and substantial improvement in sleep. When seen 1 month later, the patient reported discontinuation of the medication, for unclear reasons. With medication discontinuation, the patient's nightmares quickly recurred. The patient resumed Prazosin (1 mg at bedtime) therapy and, after 3 days, again reported resolution of the nightmares.

Discussion

Low-dose Prazosin therapy was associated with the elimination or substantial reduction of combat-related nightmares typical of PTSD for a high percentage of soldiers who presented with these distressing symptoms after their return from OIF. These open-label results are consistent with the demonstration of Prazosin efficacy for treatment-resistant, combat-related nightmares and associated sleep disruption in a placebo-controlled trial among Vietnam combat veterans with chronic PTSD.15 Although Prazosin is indicated clinically for hypertension, no incidents of dizziness, falls, or other manifestations of excessive blood pressure reduction were reported by these patients. The observed impressive reduction of combat nightmares and improved sleep, as well as the absence of adverse effects, among soldiers who recently returned from OIF provide a strong rationale for a placebo-controlled trial of Prazosin treatment for these distressing nighttime symptoms in this population.

Conclusions from these anecdotal observations must be considered preliminary, for a number of reasons. It is always possible in an open-label trial that nightmare reduction, even of the observed magnitude, was attributable to a placebo effect or the psychotherapeutic effects of being treated in a mental health setting. Also, some of the psychotropic medications being taken by more than one-half of these soldiers could have contributed to the symptomatic improvement observed during Prazosin treatment. Conversely, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors could have intensified nightmares and sleep disturbances.3 Because combat-related nightmares were not reported to have been influenced for better or worse by these medications, it is more likely that the observed nightmare reductions were attributable to Prazosin. Temporally, combat-related nightmares almost always were reduced or completely eliminated after the initiation or increase in Prazosin therapy, while the other medications remained unchanged.

It would have been more informative to have used multiple valid, reliable, rating scales to quantify nightmare frequency and intensity, sleep disturbances, other PTSD symptoms, mood symptoms, and quality of life. Unfortunately, these intensive assessments were not feasible in our busy clinic. More objective symptom ratings will be included in future, placebo-controlled, Prazosin trials. Limiting assessments to global change evaluations with the Clinical Global Impression of Change likely caused useful information to have been missed but did provide standardization of treatment response assessments. Furthermore, this patient group was not a random sample of OIF veterans with combat-related nightmares but was a self-referred, "help-seeking" group willing to admit on a postdeployment questionnaire that combat-related nightmares were a serious problem. The fact that none of the patients were abusing alcohol or other drugs as "self-medication" for nightmares and sleep disturbances (at least by self-report) might also have been atypical.

Combat-related nightmares that occur soon after evacuation from theater may represent a normal psychologic response to stress that potentially could resolve over days or weeks. However, for the patients included in this analysis and represented in the case presentations, the nightmare symptoms had persisted for months and continued to be distressing enough at the time of presentation to prompt immediate treatment. In addition, these soldiers' traumatic combat events had occurred >4 weeks before their return to their home base and thus had persisted beyond the time period acceptable for a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, diagnosis of acute stress disorder. The persistence and intensity of the nightmares and the lack of clinical improvement over time again are consistent with trauma nightmares in the context of PTSD.1

Previous Prazosin studies focused on the amelioration of nightmares among Vietnam era veterans with PTSD. Prazosin dosages that appeared effective in our study population were low (typical doses of 1 or 2 mg at night), compared with typical doses used in treating Vietnam era veterans (5-10 mg at night). Several differences in the populations emerge as possible factors for the discrepancy in required dosages, i.e., (1) our sample was young and, in general, free of medical and comorbid psychiatric disorders; (2) the exposure to combat stress in our population was recent, rather than decades in the past; and (3) the Vietnam veterans had been maintained on a larger number and wider variety of concurrent psycho tropic medications, and many had histories of alcohol abuse.14,15 However, the similarly robust reductions of combat-related nightmares during Prazosin treatment among recently combat-exposed OIF veterans and remotely combat-exposed Vietnam veterans suggest a common pathophysiologic process, involving enhanced CNS α^sub 1^-adrenergic receptor responsiveness, in both groups.

References

1. Neylan TC. Mannar CR. Metzler TJ. et al: Sleep disturbances in the Vietnam generation: findings from a nationally representative sample of male Vietnam veterans. AmJ Psychiatry 1998: 155: 929-33.

2. Friedman MJ: Future pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: prevention and treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002; 25: 427-41.

3. Brady K, Pearlstein T, Asni GM, et al: Efficacy and safety of sertraline in posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA 2000: 283: 1837-44.

4. Van Der Kolk BA, Dreyfuss D, Michaels M, et al: Fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55: 517-22.

5. Zohar J, Amital D, Miodownik C, et al: Double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of sertraline in military veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002: 22: 190-5.

6. Geracioti TD Jr. Baker DG, Ekhator NN, et al: CSF norepinephrine concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1227-30.

7. Southwick SM. Krystal JH. Bremner JD, et al: Noradrenergic and serotonergic function in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatr}' 1997; 54: 749-58.

8. Mellman TA, Kumar A, Kulick-Bell R, Kumar M, Nolan B: Nocturnal/daytime urine noradrenergic measures and sleep in combat-related PTSD. Biol Psychiatry 1995: 38: 174-9.

9. Berridge CW. Isaac SO, Espana RA: Additive wake-promoting actions of medial basal forebrain noradrenergic α^sub 1^ and β-receptor stimulation. Behav Neurosci 2003; 117: 350-9.

10. Pickworth WB. Sharpe LG. Nozaki M, Martin WR: Sleep suppression induced by intravenous and intraventricular infusions of methoxamine in the dog. Exp Neurol 1997: 57: 999-1011.

11. Hardman JG. Limbird LE. Molinoff PB. Rudden RW: Goodman and Gillman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. Ed 9. p 229. New York. NY. McGraw-Hill, 1996.

12. Menkes DB, Baraban JM, Aghajanian GK: Prazosin selectively antagonizes neuronal responses mediated by α^sub 1^-adrenoreceptors in brain. Naunyn-Schmiedebcrg's Arch Pharmarol 1981: 317: 273-5.

13. Raskind MA. Thompson C, Petrie E, et al: Prazosin reduces nightmares in combat veterans with PTSD. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 565-8.

14. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Kanter ED, et al: Reduction of nightmares and other PTSD symptoms in combat veterans by Prazosin: a placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2003: 160: 371-3.

15. Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM] 76-338, pp 218-22. Rockville, MD, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976.

Guarantor: MAJ Christine Maura Daly, MC USA

Contributors: MAJ Christine Maura Daly, MC USA; LTC Michael E. Doyle, MC USA; Murray Radkind, MD;

Elaine Raskind, MD; MAJ Colin Daniels, MC USA

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Jun 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved