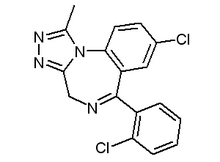

We performed a double-blind single-dose placebo/hypnotics crossover study randomized within groups to test the potential problems that a group of normal subjects, including subjects who snore, may face using hypnotic medications. Two benzodiazepine hypnotics--triazolam, 0.25 mg, and flunitrazepam, 2 mg tablets--were considered. Subjects were monitored with nocturnal polysomnography, including esophageal pressure (Pes) monitoring as a measure of respiratory efforts, and were given daytime performance tests. Results were analyzed for the total nocturnal sleep period and also by thirds of the night in consideration of the different half-lives of the studied drugs. Three specific respiratory variables were evaluated: mean breathing frequency for selected unit of time, "[delta]Pes" (esophageal pressure at peak end-expiration minus Pes at peak end-inspiration) expressed in cm [H.sub.2]O, and the ratio of [delta]Pes/[delta]TI (inspiratory time), taken as an index of respiratory drive calculated for each respiratory cycle. There was no significant increase in either the respiratory disturbance index or the oxygen desaturation index (number of drops in arterial oxygen saturation of 4% or more per hour of sleep, as measured by pulse oximetry). There was a significant increase in mean breathing frequency with flunitrazepam compared with placebo, as well as a significantly larger percentage of time during sleep with [delta]Pes above 10 cm [H.sub.2]O (taken as a cutoff point for normal respiratory effort) with both triazolam and flunitrazepam compared with placebo. These respiratory changes, even if significant, were minor but may become a liability in association with specific abnormalities.

Key words: benzodiazepine; breathing; normal subjects; sleep; upper airway resistance

The effect of benzodiazepine hypnotics on sleep structure has been studied previously in normal populations. Some of the beneficial effects of hypnotics, however, such as improvement of sleep maintenance, may actually be a disadvantage in certain populations, as they may have a negative impact on breathing during sleep. Hypnotics can impact on breathing during sleep in many ways: they may decrease central respiratory drive, increase upper airway resistance, particularly by acting on upper airway dilators,(1) (2) (3) and decrease the arousal response, particularly in older subjects.(3),(4) Recently, it has become clear that regular snoring can be a clinical sign of subtle forms of sleep-disordered breathing, such as upper airway resistance syndrome.(5) Abatement of a defense mechanism, such as the arousal response from sleep, may be a tolerable side effect in normal subjects, but may not be acceptable in a known snorer who experiences frequent upper airway infections.

In a general population of noncomplaining adults that included simple snorers, we investigated the effects of a single dose of two benzodiazepine hypnotics, triazolam, 0.25 mg, and flunitrazepam, 2 mg. These drugs were selected because of their frequent prescription in cases of transient insomnia and jet lag, and because of their very different pharmacologic half-lives (triazolam, 90 to 120 min, vs Flunitrazepam, 720 to 790 mins).(6) Considering the known potency of these drugs, we investigated their impact on peak negative inspiratory esophageal pressure (Pes), an index of respiratory effort, and on the ratio of [delta]Pes over [delta]TI (inspiratory time), an index of respiratory drive, during sleep.

The effects of benzodiazepines on control of breathing and ventilation during awake periods have been widely investigated.(15) Less work has been performed on these effects during sleep, but it has been shown that benzodiazepines at bedtime decrease the activity of upper airway dilators (genioglossus muscles) and may induce complete airway obstruction during sleep in patients with repetitive obstructive hypopneas.(16) In the recent past, Biberdorf et al(17) reported that temazepam, a benzodiazepine with a half-life not too different from that of flunitrazepam, had no detrimental effect on patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration and cardiac failure. Not only was there no worsening of nighttime [SaO.sub.2], but also the degree of sleep fragmentation was decreased. Thus, evaluation of the clinical impact of the different types of benzodiazepines on breathing during sleep in different pathologic conditions is highly recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT: The authors wish to express their gratitude to Julia Gaedt and Martin Grundner for their assistance in data evaluation and preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

(1) Hwang JC, St Johns WM, Bartlett D. Afferent pathways for hypoglossal and phrenic responses to change in upper airway pressure. Respir Physiol 1983; 49:341-55

(2) Hwang JC, St Johns WM, Bartlett D. Respiratory related hypoglossal nerve activity: influence of anaesthetics. J Appl Physiol 1983; 55:785-92

(3) Leiter JC, Knuth SL, Krol RC, et al. The effect of diazepam on genioglossus muscle activity in normal human subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985; 132:216-19

(4) Dolly FR, Block AJ. Effect of flurazepam on sleep disordered breathing and nocturnal desaturation in asymptomatic subjects. Am J Med 1982; 73:239-43

(5) Guilleminault C, Stoohs R, Clerk A, et al. A cause of excessive daytime sleepiness: the upper airway resistance syndrome. Chest 1993; 104:781-87

(6) Nicholson AN. Hypnotics: clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1994; 355-63

(7) Rechtschaffen A, Kales A, eds A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring systems for sleep stages of human subjects. Los Angeles: UCLA Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, 1968

(8) Zerssen D. Selbstbeutteilungsskalen zur Abschatzung des `subjektiven Befundes' in psychopathologischen Querschnitt-und Langsschnitt Untersuchungen. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkrank 1973; 217:299-314

(9) Schwarzenberger-Kesper F, Becker H, Penzel T, et al. Die exzessive Einschlafneigung am Tage (EDS) beim Apnoe PatientenDiagnostische Bedeutung und Objektivierung mittels Vigilanz-test und synchroner EEG Registrierung am Tage Prax Klin Pneumol 1987; 41:401-05

(10) Oswald WD, Roth E. Der Zahlenverbindungstest (ZVT). Gottingen: Hogreve, 1978

(11) American Sleep Disorders Association (ASDA) Report. EEG-arousal: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the sleep disorders atlas task of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep 1992; 151:75-184

(12) Guilleminault C. Sleep/wake disorders--indications and techniques. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley, 1978

(13) Gould GA, Whyte KF, Rhind GB, et al. The sleep hypopnea syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 142:295-300

(14) Milic-Emili J, Grassino AE, Whitelaw WA. Measurement and testing of respiratory drive. In: Hornbein G, Lenfant C, eds. Regulation of breathing: lung biology in health and disease (vol 17). New York: Marcel Dekker, 1981; 675-743

(15) Guilleminault C, Cummiskey J, Silvestri R. Benzodiazepines and respiration during sleep. In: Usdine E, Skolnick P, Tallman YF, et al, eds. Pharmacology of benzodiazepines. London: MacMilland Press, 1982; 229-36

(16) Guilleminault C. Benzodiazepines, breathing and sleep. Am J Med 1990; 88:253-85

(17) Biberdorf DJ, Steens R, Millar TW, et al. Benzodiazepines in congestive heart failure: effects of temazepam on arousability and Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Sleep 1993; 16:529-38

COPYRIGHT 1996 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group