Deodorants, mouthwashes, toothpastes, soaps, cutting boards, baby toys, high chairs, and carpeting. Even sweat-socks, underwear, and hunting clothes. On her visits to the local Wal-Mart, Maura J. Meade of Allegheny College in Meadville, Pa., found examples of those products and others that incorporate the bacteria-killing agent triclosan. "It's all over the place," she says.

That pervasiveness may carry a price, Meade and two other investigators warned at this week's American Society for Microbiology meeting in Los Angeles. Each reported studies on triclosan-resistant microbes and expressed concern that the antiseptic's increasing popularity will encourage the evolution of bacteria impervious to drugs. For the moment, however, that worry remains theoretical, the scientists acknowledge.

"We may compromise the effectiveness of still-useful antibiotics," says Herbert P. Schweizer of Colorado State University in Fort Collins. "I don't want to ring the alarm bell too loudly, but I do think we have to start ringing it."

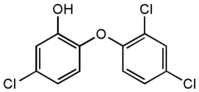

Easily incorporated into liquids, fabrics, and solid surfaces, triclosan's use has soared since its introduction about 3 decades ago. Scientists once believed that bacteria can't develop resistance to triclosan because it acts more as a grenade than as a bullet. They thought the antiseptic killed bacteria in multiple ways rather than targeting a single protein, the modus operandi of most antibiotics.

In the past few years, however, biologists have discovered that triclosan's main method of killing is very specific. It inhibits an enzyme involved in fatty acid synthesis. They've also shown that some bacteria with mutations in that enzyme's gene can resist triclosan. More troubling, an antibiotic commonly employed against the tuberculosis bacterium targets the same enzyme, raising the possibility that triclosan use will lead to new drug-resistant strains of the microbe.

In his study, Schweizer focused on a second way that bacteria fend off triclosan. He found that almost all strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a deadly microbe that often strikes people with weak immune systems, thwart triclosan because of the action of so-called efflux pumps. The pumps remove the antiseptic and other toxic substances from the bacteria.

When Schweizer mutated the gene for one key pump, the bacteria quickly regained their triclosan defense by increasing production of other efflux pumps. Since the pumps also rid bacteria of many antibiotics (SN: 2/12/00, p. 110), he worries that triclosan's ubiquity will promote the evolution of microbes with multiple-drug resistance.

Peter Gilbert of the University of Manchester in England questions the way that manufacturers use triclosan in products such as cutting boards. His study found that hard surfaces impregnated with the compound slowly release triclosan. This could expose nearby bacteria to sublethal concentrations of the agent, a situation that promotes development of resistance.

To preserve the agent's effectiveness, Gilbert argues that triclosan-treated surfaces shouldn't be used unless there's a demonstrated health benefit. Few manufacturers can offer such proof, he says.

"You wouldn't want your cutting board at home to compromise the of the gloves your surgeon wears agrees Meade, noting that hospitals also use triclosan-treated clothes and gear.

Gilbert also suggests that triclosan's widespread use encourages poor hygiene. "There's a tendency to become complacent," he says.

Meade adds that overuse of triclosan will reduce the time until the agent stops working. She notes that her research group has found several strains of bacteria in nature that readily grow on the compound and one that may even use it as an energy source. Considering that bacteria frequently acquire traits from one another by exchanging genes, Meade says, triclosan's days are numbered.

COPYRIGHT 2000 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group