Cleanliness is next to impossible, as the old joke goes, but you'd never know it at your local supermarket. There you'll find antibacterial hand soaps, antibacterial laundry detergents, antibacterial toothpastes and antibacterial toys. In some places, you can buy antibacterial mattresses, chopsticks and polyester. There are so many such products on the market today that antibacterials have become a $16 billion-a-year industry. The Washington Post reports that two-thirds of all liquid soaps on American store shelves today contain antibacterial agents.

>From this evidence alone, you might assume we'd be living in a germ-free environment by now, with infectious diseases all but wiped out. Either that, or we've become a nation of germophobes, unable to shake hands or turn a doorknob without immediately pulling out a Handi Wipe.

There's mote evidence for the later than for the former, which raises interesting questions. In fact, those disorders directly attributable to the strength of our immune systems such as asthma and allergies are on the rise. The number of asthma cases doubled from 1985 to 2000. And in the past 10 years, 700 new antibacterial products have been added to the market, leading some experts to suspect a troubling connection.

The possibility that we may be too clean for our own good has led some researchers to fear that antibacterials (and the desire for cleanliness to which they are a response) may actually be tendering us more rather than less vulnerable to disease. Whether that's true or not probably won't be established for years, but that doesn't mean you can't begin to make intelligent choices about your own approach to health based on existing evidence.

Hygiene Hypothesis

To grasp the science behind the experts' concern, it's important to familiarize yourself with the "Hygiene Hypothesis." That phrase attempts to convey the notion that some efforts to protect ourselves from germs may have proven counterproductive.

"The Hygiene Hypothesis seems to have taken root when it was observed that people with higher socioeconomic status--and therefore the cleanest living environments--also have the greatest problems with allergies and infectious diseases," explains James Dahlgren, MD, a University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) toxicologist. "You're born with no immunities except what your mother gives you, which is why breast-feeding is so important. It isn't until you're 6 months old that your own immune system kicks in to protect you. The basic idea of the Hygiene Hypothesis is that the immune system has to be stimulated to develop properly, so that if a home is too clean, children don't develop the immunities that will protect them later in life."

Linked to this theory is the fact, first observed in highly sterile hospital settings, that pediatric patients treated with antibiotics were cured of one disease but were left vulnerable to others. "The antibiotics killed off the so-called non-resistant bacteria, but this left only the resistant ones--the ones the antibiotics could not kill--as a greater percentage in the body," says Dahlgren. This allowed the scrappiest bacteria to mutate and colonize at will, weakening the children and making it more difficult than ever for them to recuperate.

"It was out of that concern that doctors for years have been saying that you should not use antibiotics unless you absolutely have to--and then use the narrowest ones you can," Dahlgren says. "Unfortunately the pharmaceuticals industry has been pushing the broadest-spectrum antibiotics they have, which are also the most expensive. These kill more and more of the non-resistant bacteria, leaving more of the resistant ones." The phenomenon can be compared, the Boston-based Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics (APUA) explains, "to weeds that have overgrown a lawn where the grass has been completely destroyed by an overdose of herbicides."

Antibiotic Paradox

Stuart Levy, MD, who is chairman of the APUA, author of The Antibiotic Paradox: How the Misuse of Antibiotics Destroys Their Curative Powers and director of the Center for Adaptation Genetics and Drug Resistance at the Tufts University School of Medicine, says the idea that "germs should be destroyed, and kids should be raised in a sterile home is a mistake. If we over-dean and sterilize, children's immune systems will not mature. What worries me is that if we continue using antibacterials, we won't see [problems] until children get older, maybe 10 years from now."

Maybe so, but Sandra Kemmerly, MD, an infectious diseases specialist at the Ochsner Clinic Foundation in New Orleans, notes that dire conclusions drawn from the Hygiene Hypothesis "have been extrapolated informally into a lot of areas for which there is still no real scientific support."

But Kemmerly does acknowledge that these conclusions may offer significant insights nonetheless. People who are raised in less pristine environments often do seem hardier than those in more pristine ones. An October 2000 study by the National Jewish Medical & Research Center in Denver, for example, showed that household dust levels are higher in rural communities than urban ones--and that this dust appears to have a protective effect against allergies and asthma. Research presented in March 2003 to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology showed that exposure to a dog in the first year of life seems to strengthen a baby's immune system.

Philip Tierno, director of Microbiology and Clinical Immunology at New York University Medical Center, contends that the abuse of antibiotics, while real, and the recent rise in the popularity of antibacterials are simply unrelated phenomenon without any scientific support.

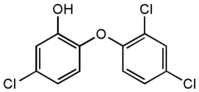

But the question remains: Are antibacterial soaps any better for you than non-antibacterial soaps? It's not likely, in large part because of the way they are used. The antibacterial component of soaps--usually triclosan--must be left on the skin for about two minutes for it to kill bacteria. Even if we were that patient and the antibacterial soaps went to work, they would kill bacteria indiscriminantly--the good with the bad. Also, these soaps tend to dry the skin excessively, which is why pediatricians often recommend against their use on little hands and Faces.

What most experts agree on--Kemmerly, Levy, Dahlgren and Tierno included--is that even if it were advisable to sterilize our homes, antibacterial household cleansers can't do it. A study published in the March 2, 2004 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine suggests that many of these commercially available products may not ward off disease a all. In the study, families that used only antibacterial cleansers for a year were just as prone to common illnesses as those who used standard cleansers, in large part, it seems, because most fevers, sore throats and runny noses are caused by viruses, not by bacterial infections.

Ironically enough, most Americans fail to take other, more important precautions to protect themselves in areas that are effective. "I've seen people wipe down their kitchen counters by putting antibacterial soap on used sponges-sponges--that are veritable Petri dishes for bacteria," Kemmerly says. "This makes no sense because the greatest dangers we face from infectious diseases are through the careless way we handle foods, and here we can exercise some control."

Breeding Grounds

Cutting boards are also breeding grounds for bacteria. "I prefer plastic cutting boards to butcher blocks because you can throw [plastic ones] into the dishwasher, and they clean up better," Kemmerly says. "I use paper towels to wipe down my countertops because I can throw the paper towel away. If you use cloth dish towels, you tend to use them over and over, and people are forever picking them up and wiping their hands on them, so it is impossible to keep them clean."

We run far more risks of getting sick from the bacteria that collect on cutting boards, countertops and other surfaces--on what immunologists call "fomites"--than we do from getting sneezed on. The average desk in an American office, where workers frequently eat, has been found to contain 400 times more bacteria than an average toilet seat, which, in a March 2002 study by the University of Arizona, also had lower levels of bacteria than telephones, water fountain handles, microwave door handles and computer keyboards. "We don't think twice about eating at our desks, even though the average desk has 100 times more bacteria than a kitchen table," says Charles Gerba, the University of Arizona microbiologist who led the study.

None of this is to suggest that some consumer products can't be useful. Wiping down your desk with disinfecting wipes once a day, the University of Arizona study found, can decrease bacterial levels by 99.9 percent (see "Keeping Germ-Free Safely," p. 66).

Realistic expectations are helpful, too--and reassuring. A little dust in the house is not a bad thing because children's immune systems need to be stimulated. "There are strong parallels here to life in general," Dahlgren says. "If you shelter your kids too much, they will have no resources for dealing with the stresses and strains of life."

"Look, as a mother, when a pacifier fell on the floor, I admit I didn't sterilize it,". Kemmerly says. "We don't live in a sterile world. There are bacteria that live on us and in us for a purpose. We were never supposed to live in a bubble."

Keeping Germ-Free Safely

What you can do to keep germfree without jeopardizing your immune system:

* Clean sponges frequently by putting them in the dishwasher--and dry them thoroughly.

* Use paper towels to wipe countertops.

* Use plastic cutting boards, which can be cleansed with one teaspoon of chlorine bleach per quart of water, according to the US Department of Agriculture. Allow to air dry.

* For mildew in bathrooms and kitchens, the Princeton, New Jersey-based Children's Health Environmental Center recommends borax combined with vinegar.

* Use hand sanitizers when water for washing is unavailable.

* Do not allow toothbrushes to rest together in cups or drawers, says Alan Greene, MD, of the Stanford University School of Medicine.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Vegetarian Times, Inc. All rights reserved.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group