BACKGROUND. Combination oral therapy is often used to control the hyperglycemia of patients with type 2 diabetes. We compared the effectiveness of metformin and troglitazone when added to sulfonylurea therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes who had suboptimal blood glucose control.

METHODS. We used a randomized 2-group design to compare the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of troglitazone and metformin for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus that was inadequately controlled with diet and oral sulfonylureas. Thirty-two subjects were randomized to receive either troglitazone or metformin for 14 weeks, including a 2-week drug-titration period. The primary outcome variable was mean change in the level of glycosylated hemoglobin (Hb [A.sub.1c]) from baseline. Secondary outcomes included mean changes from baseline in fasting plasma glucose and C-peptide levels, renal or metabolic side effects, and symptomatic tolerability.

RESULTS. The addition of either troglitazone or metformin to oral sulfonylurea therapy significantly decreased Hb [A.sub.1c] levels. Both treatment regimens also significantly reduced fasting plasma glucose and C-peptide levels. We found no significant differences between the treatment arms in efficacy, metabolic side effects, or tolerability.

CONCLUSIONS. Our results demonstrate that troglitazone and metformin each significantly improved Hb [A.sub.1c], fasting plasma glucose, and C-peptide levels when added to oral sulfonylurea therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes who had inadequate glucose control.

KEY WORDS. Diabetes mellitus, non-insulin-dependent; metformin; drug therapy, combination. (J Fam Pract 1999; 48:879-882)

In 1998 an estimated 9.5 million people had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the United States.[1] Tight control of blood glucose concentrations to near-normal levels has been shown to reduce the microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes without increasing major macrovascular complications.[2,3] However, control of blood glucose is complex and involves multiple organ systems. Patients with type 2 diabetes often do not achieve desirable glucose control despite the use of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin. Insulin resistance -- the diminished ability of insulin to exert its biological activity over a broad range of glucose levels -- may contribute to the difficulty in controlling type 2 diabetes.[4,5]

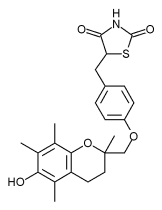

Thiazolidinediones represent a newer class of drugs that affect insulin resistance? Troglitazone (Rezulin) is the first drug in this class to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Troglitazone can be used in combination with a sulfonylurea or insulin to improve glycemic control.[8-10] Troglitazone increases the responsiveness of insulin-dependent tissues through a mechanism thought to involve receptors that regulate the transcription of a number of insulin-responsive genes.[11,12] It increases insulin-dependent glucose disposal in skeletal muscle, enhancing the effects of circulating insulin.

Metformin (glucophage) lowers plasma glucose by decreasing hepatic glucose output through the inhibition of gluconeogenesis and by increasing peripheral glucose use by skeletal muscle. It is a biguanide that was introduced in Europe in 1957 and has been available in the United States since 1995.[13,14] Metformin is indicated in patients with type 2 diabetes as a monotherapy along with diet; it can also be used concomitantly with a sulfonylurea or insulin.[15,16] The efficacy of metformin on glycemic control has been demonstrated as a monotherapy and in combination with a sulfonylurea.[16,17]

Although there are data to support the use of metformin or troglitazone in combination with a sulfonylurea,[8-10,14-16] randomized comparisons of the relative effects of these combinations on glycemic control are lacking. Information about the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and cost of these combination therapies may help in pharmacotherapy decision making. Our primary goal was to compare the effects of troglitazone with those of metformin on the Hb [A.sub.1c] levels of patients with type 2 diabetes who were already receiving sulfonylurea therapy. Secondary outcomes included the comparative effects of these combinations on fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and C-peptide levels. We also compared safety, tolerability, and cost of the 2 drugs.

METHODS

STUDY SUBJECTS

We studied 32 patients (20 men, 12 women) with type 2 diabetes who were already taking a sulfonylurea. We randomly screened individuals found in a database of family medicine patients who had been given a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Patients were eligible if they were aged 30 to 75 years, had poorly controlled diabetes defined by an Hb [A.sub.1c] level between 8.5% and 16% at the screening visit, and were able to give informed consent. We excluded women of childbearing potential. The other exclusion criteria were: a history or laboratory evidence of renal or hepatic insufficiency; a history of alcohol abuse (including binge drinking within the past year); concomitant treatment with insulin, cholestyramine, potentially nephrotoxic drugs, or glucocorticoids (except topical or inhaled glucocorticoids); plans for radiographic studies involving the use of intravenous iodinated contrast during the course of our study; and known intolerance or sensitivity to a biguanide or troglitazone. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center.

STUDY DESIGN

At baseline we randomized the patients to receive either metformin or troglitazone for a 14-week period. The study was divided into 2 phases: a 2-week dose-titration period and a 12-week open-label comparison of metformin and troglitazone. If randomized to metformin, the patient took 500 mg with the evening meal for 2 days, then 500 mg twice dally with the morning and evening meals for 5 days. During the second week of the study, the patient took 500 mg with the morning meal and 1000 mg with the evening meal. After week 2, all patients randomized to metformin therapy were taking 1000 mg with the morning and evening meals. Patients randomized to troglitazone took 200 mg dally with the evening meal for 2 weeks and then 400 mg daily for the remaining 12 weeks of the study. If at any time during the study a patient experienced a FPG of less than 80 mg/dL, the oral sulfonylurea was decreased by one half of the original dose and then discontinued if further blood glucose readings were less than 80 mg/dL on more than one occasion.

Patients were required to make a screening visit at least 1 week before entry into the trial. We obtained a past medical history, body weight and height, and blood tests (serum creatinine, serum bicarbonate, liver enzymes, Hb [A.sub.1c], FPG, and C-peptide levels). We recorded body weight and repeated blood tests 6 to 8 weeks after randomization and at the end of the study period (14 weeks). In addition, participants randomized to troglitazone had monthly liver enzyme tests. We also instructed patients to perform home blood glucose monitoring twice dally, in the morning before breakfast and at bedtime. We validated blood glucose monitors for accuracy by checking control solutions and performing check strip tests at study visits. Patients received standardized information about diabetes from a certified diabetes educator consisting of a general overview of diabetes mellitus, a medication review, instructions for blood glucose monitoring, a review of complications associated with diabetes, and nutritional advice. Each patient was given the same written information about diabetes and counseled on the signs and symptoms of high and low blood glucose. No patient enrolled in this trial reported problems reading or understanding written instructions. We assessed compliance using pill counts during each scheduled follow-up visit. We asked patients about adverse events at each visit after beginning drug therapy; any reported events were recorded.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We performed an analysis of efficacy by intention to treat. We included all patients who received at least one dose of troglitazone or metformin, and selected a sample size adequate for detecting clinically meaningful differences in treatment effects. A sample of 16 patients in each group allowed detection of a mean absolute difference in Hb [A.sub.1c] level reduction between groups from a baseline of 1.2% ([+ or -] 0.2%) with a power greater than 0.80 ([Alpha] = 0.05, 2-tailed test). We evaluated baseline differences between treatment groups using analysis of variance and chi-square procedures. Paired t tests were used to examine changes in variables over time. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Personal Computers (Version 8.0, SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Ill).

RESULTS

The baseline demographic and disease-related characteristics of the participants are outlined in Table 1. There were no significant differences at baseline between treatment groups with respect to age; body mass index (BMI); Hb [A.sub.1c], FPG, or C-peptide levels; or the duration of diabetes. Ninety-seven percent of the patients took their assigned medication for the 14 weeks of the study. All patients were receiving an oral sulfonylurea, with 85% taking glipizide (Glucotrol XL) 10 mg to 20 mg per day, 9% taking glimepiride (Amaryl) 4 to 8 mg per day, and 6% taking glyburide (generic or DiaBeta) 10 to 20 mg per day.

TABLE 1 Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants Before Randomization

Note: No baseline data characteristics were statistically different between the 2 treatment groups at P <.05.

(*) Normal range = 65 mg/dL to 115 mg/dL

([dagger]) Normal range = 4.2% to 5.9%.

([double dagger]) Normal range = 0.9 ng/mL to 4.0 ng/dL.

Table 2 contains the changes in glycemic control parameters observed in each treatment group. At the end of a 3-month treatment period, Hb [A.sub.1c] values decreased significantly for each group when compared with the values obtained at baseline. The mean Hb [A.sub.1c] level among those receiving metformin fell from 9.9% [+ or -] 1.6 to 7.8% [+ or -] 1.3 (P [is less than] .001). Among patients in the troglitazone treatment group, the mean Hb [A.sub.1c] level fell from 10% [+ or -] 1.6 to 7.4% [+ or -] 1.7 (P [is less than] .001). The mean FPG level fell from 229 mg/dL [+ or -] 75 to 138 mg/dL [+ or -] 36 (P [is less than] .001) in the patients receiving metformin and from 210 mg/dL [+ or -] 79 to 127 mg/dL [+ or -] 33 (P [is less than] .001), in those receiving troglitazone. For each treatment group this amounts to a 60% reduction in FPG levels. For those patients receiving metformin, fasting C-peptide levels fell from 6.9 ng/mL [+ or -] 2.3 to 4.7 ng/mL [+ or -] 1.6 (P [is less than] .001), and in troglitazone-treated patients, it fell from 6.5 ng/mL [+ or -] 3.9 to 4.5 ng/mL [+ or -] 2.3 (P = .004). Although both troglitazone and metformin significantly improved glycemic control, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups in any treatment effect measured. In addition, BMI did not significantly change from baseline to the end of the study in either treatment group.

TABLE 2 Pretreatment and Posttreatment Differences in Hb [A.sub.1c], FPG, and C-Peptide Levels

Hb [A.sub.1c] denotes glycosolated hemoglobin; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Safety was assessed on the basis of the results of serum FPG levels, creatinine and liver function tests, and home glucose monitoring. There were no elevations in liver enzymes or serum creatinine in those individuals receiving either troglitazone or metformin. No patient reported hypoglycemic symptoms or blood glucose values of less than 70 mg/dL on more than one occasion. Tolerability was evaluated using a questionnaire of potential side effects that was answered during each study visit. There was one dropout from the trial in the metformin treatment arm, which was attributed to moderate nausea and diarrhea after 1 month of treatment. Six additional participants in the metformin group reported mild nausea and bloating in the first 2 weeks of treatment with metformin; however, no other adverse effects were ascribed to the study medications.

DISCUSSION

There has been much interest in combined pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes, especially when target Hb [A.sub.1c] levels are not achieved with monotherapy. The American Diabetes Association recommends that the goal of treatment in type 2 diabetes is an Hb [A.sub.1c] level of less than 7%, with additional action suggested at values greater than 8%.[18] This small study addressed patients with type 2 diabetes who were already receiving treatment with moderate to maximum doses of a sulfonylurea. The patients in this study were obese (mean BMI = 33 kg/[m.sup.2]) and had uncontrolled diabetes as evidenced by baseline Hb [A.sub.1c] levels. Our results show that metformin and troglitazone had very similar efficacy for those patients in terms of reductions in Hb [A.sub.1c], FPG, and C-peptide levels when used in combination with a sulfonylurea. Furthermore, safety and tolerability in terms of symptomatic adverse events, hypoglycemia, changes in serum creatinine, and changes in liver enzymes were good for both combinations during the 14 weeks of this clinical trial. Previous studies[9,10,14,16] have shown these combinations effective, but those studies did not directly compare them in a controlled fashion. Troglitazone and metformin are both approved by the FDA for combination therapy with a sulfonylurea. Although metformin is also FDA approved as a monotherapy, it is common practice to start with a sulfonylurea when type 2 diabetes is diagnosed.

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) showed metformin to be beneficial as a monotherapy for obese patients with type 2 diabetes, but raised concern about combination sulfonylurea/metformin therapy.[19] In the UKPDS, metformin was shown to reduce overall mortality in obese patients with serum creatinine levels less than 1.5 mg/dL, but increased mortality was associated with the addition of metformin to sulfonylurea therapy. The baseline differences between patients treated with metformin alone and those for whom metformin was added to a sulfonyurea (plus the small number of deaths overall) led the UKPDS investigators to question the validity of this observation. Special precautions are recommended when prescribing metformin,[20] mainly because of potential problems with severe lactic acidosis observed in the past with another biguanide (phenformin). Accordingly, metformin is contraindicated in congestive heart failure, in the presence of renal or hepatic insufficiency, during periods of hypoxemia or dehydration, and for heavy alcohol drinkers. It should also be withheld before, during, and after the administration of iodinated intravenous contrast. Tolerability of metformin can be problematic during the dose-titration phase for some patients because of gastrointestinal side effects, but adherence to treatment can be optimized by educating patients that this is usually a transient side effect.

Troglitazone has been associated with elevated hepatic enzymes in approximately 2% of patients in clinical trials; very rare severe or fatal hepatic dysfunction has also been reported.[21] Accordingly, the manufacturer recommends periodic assay of serum alanine aminotransferase levels (baseline and monthly for the first year of therapy, then quarterly).[22] Similar laboratory monitoring is not required for metformin.

Simplicity of a prescribed drug regimen is a consideration for patients, especially with regard to compliance. Metformin requires at least twice-daily administration; troglitazone can be taken once per day. Comparative drug costs are also important to consider. As of 1999, the average wholesale cost in the United States for a 1-month supply of the doses in our study is approximately $142 for troglitazone and $75 for metformin.[23] Newer thiazolidinediones, such as rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, will add competition and continued scrutiny to the efficacy, safety, and costs of this drug class.

CONCLUSIONS

Metformin and troglitazone improved glycemic profiles and C-peptide levels with equal success with no significant differences in safety or tolerability. Although our study had sufficient power to detect a clinically meaningful difference in Hb [A.sub.1c] reduction, it was based on a small number of patients and a short study duration. The true test of the effectiveness of these combination therapies must come from large clinical trials of sufficient duration that assess their effects on diabetes-related morbidity and mortality.

REFERENCES

[1.] Harris MI. Diabetes in America: epidemiology and scope of the problem. Diabetes Care 1998:21(suppl 3);C11-4.

[2.] UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:833-53.

[3.] Ohkubo Y, Kishikawa H, Arald E, et al. Intensive insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic microvascular complications in Japanese patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: a randomized prospective 6 year study. Diab Res Clin Prac 1995; 28:103-17.

[4.] Iwamoto Y, Koska K, Kuzuya T, Akanuma Y, Shigeta Y, Kaneko T. Effects of troglitazone. Diabetes Care 1996; 19:151-6.

[5.] Polonsky K, Sturis J, Bell GI. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus -- a genetically programmed failure of the beta cell to compensate for insulin resistance. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:777-83.

[6.] Nolan JJ, Ludvic B, Beerdsen P, Joyce M, Olefsky J. Improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in obese subjects treated with troglitazone. N Engl J Med 1994; 331:1188-93.

[7.] Inzucchi SE, Maggs DG, Spollett GR, Page SL, Rife FS, Walton V, Shulman GI. Efficacy and metabolic effects of metformin and troglitazone in type II diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:867-72.

[8.] Schwartz S, Raskin P, Fonseca V, Graveline JF. Effect of troglitazone in insulin-treated patients with type II diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:861-6.

[9.] Iwamoto Y, Kosaka K, Kuzuya T, Akanuma Y, Shigeta Y, Kaneko T. Effect of combination therapy of troglitazone and sulphonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes who were poorly controlled by sulfonylurea therapy alone. Diabetic Med 1996; 13:365-70.

[10.] Horton ES, Whitehouse F, Ghazzi MN, Venable TC, Whitcomb RW. Troglitazone in combination with sulfonylurea restores glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 1998; 21:1462-9.

[11.] Prigeon RL, Kahn SE, Porte D. Effect of troglitazone on B cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glycemic control in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83:819-23.

[12.] Sparano N, Seaton TL. Troglitazone in type II diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy 1998; 18:539-48.

[13.] Bailey CJ, Path MRC, Turner RC. Metformin. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:574-9.

[14.] DeFronzo RA, Goodman AM, Multicenter Metformin Group. Efficacy of metformin in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:541-9.

[15.] Daniel JR, Hagmeyer KO. Metformin and insulin: is there a role for combination therapy? Ann Pharmacother 1997; 31:474-80.

[16.] Herman LS, Schersten B, Bitzen PO, Kjellstrom T, Lindgarde F, Melander A. Therapeutic comparison of metformin and sulfonylurea, alone and in various combinations. Diabetes Cake 1994; 17:1100-9.

[17.] Jhansen K. Efficacy of metformin in the treatment of NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1999; 22:33-7.

[18.] American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1999; (supp 1):S32-41.

[19.] UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 1998; 352:854-65.

[20.] Sulkin TV, Bosman D, Krentz A. Contraindications to metformin in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1997; 20:925-8.

[21.] Watkins PB, Whitcomb RW. Hepatic dysfunction associated with troglitazone. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:916-7.

[22.] Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals. Troglitazone package insert. Morris Plains, NJ: Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals, 1999.

[23.] Medical Economics Co. Drug topic redbook. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Co, Inc, 1999:18.

Submitted, revised, July 15, 1999. From the Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem (J.K.K., R.M., J.H.S.) and the Department of Family Practice, University of Kentucky, Lexington (K.A.P.). Reprint requests should be addressed to Julienne K. Kirk, PharmD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157. E-mail: jkirk@wfubmc.edu.

Julienne K. Kirk, PharmD, CDE; Kevin A. Pearce, MD, MPH; Robert Michielutte, PhD; and John H. Summerson, MS Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and Lexington, Kentucky

COPYRIGHT 1999 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group