Passatempo virus was isolated during a zoonotic outbreak. Biologic features and molecular characterization of hemagglutinin, thymidine kinase, and vaccinia growth factor genes suggested a vaccinia virus infection, which strengthens the idea of the reemergence and circulation of vaccinia virus in Brazil. Molecular polymorphisms indicated that Passatempo virus is a different isolate.

**********

Since 1999, an increasing number of exanthemous outbreaks affecting dairy cattle and cow milkers in Brazil have been reported (1-3). These outbreaks were related to poxvirus infections, which resulted in economic losses to farmers and affected the health of humans and animals. Here we report a vaccinia virus (VACV) outbreak that emerged in March 2003 in the town of Passa-Tempo, Minas Gerais State, Brazil.

The Study

The outbreak area is characterized by small rural properties with diverse crops, pasturelands, and surrounding fragments of Atlantic Forest. Its climate is tropical, with a relatively severe dry season, generally from April to September (4).

All dairy farms were similar, consisting of a main house with corrals and pasture fields generally with unsophisticated infrastructure. All milking was manually performed by milkers, typically without strict aseptic measures, which could have contributed to the spread of the virus among the herd and milkers. Cows exhibited lesions on teats and udders that resembled the clinical features observed during other Brazilian VACV outbreaks (1). Initial acute lesions were associated with a roseolar erythema with localized edema that led to the formation of vesicles. The vesicles rapidly progressed to papules and pustules, which subsequently ruptured and suppurated. Typically, a thick dark scab followed, but the formation of large areas of ulceration was also common. The course of infection lasted from 3 to 4 weeks. Different stages of lesions were present, ranging from papules to vesicles, pustules, and crusts (Figure 1). Moreover, because of secondary infections, some cows had mastiffs (Figure 1). Calves became infected, showing lesions on oral mucosa and muzzles (Figure 1). Several infected milkers reported lesions on their hands, which were apparently transmitted by unprotected contact with sick cattle (Figure 1). In addition, infected persons reported severe headache, backache, lymphadenopathy, and high fever.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

For virus isolation, crusts were collected from 5 cows and 1 calf, macerated, and added to the chorioallantoic membrane of embryonated eggs (2). The whitish pockmarks produced on chorioallantoic membranes resembled VACV pocks, differing from the red hemorrhagic ones produced by cowpox virus (CPXV) (online Appendix Figure 1; available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/ vol11no12/05-0773_appl.htm). Blood from affected animals was collected for neutralization assays (5). Serologic cross-reactivity of antibodies to VACV-Western Reserve (WR) strain was detected in all samples, and titers of these serum samples were [greater than or equal to] 640 U/mL (data not shown).

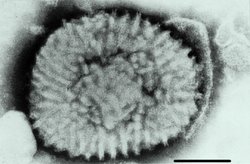

Transmission electron microscopy of isolates (6) showed a morphologic pattern typical of orthopoxviruses (online Appendix Figure 2; available at http://www.cdc. gov/ncidod/EID/vol11no12/05-0773_app2.htm). No A-type inclusion body (ATI) was seen, reinforcing the conclusion that this virus was likely not a CPXV, but a VACV. Viral DNAs were extracted (6) and used as template for ati gene restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (7). The ati RFLP patterns of all isolates were identical to those of Aracatuba virus (ARAV) (1) and other VACV strains previously isolated in our laboratory (unpub. data); they were similar to those of VACV-WR and completely different from those of CPXV-Brighton Red (BR) (online Appendix Figure 3; available at http://www. cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol11no12/05-0773_app3.htm). Since all isolates showed the same ati RFLP pattern, one was cloned, purified, titrated (1,6), and named Passatempo virus (PSTV).

[FIGURES 2-3 OMITTED]

To better identify this etiologic agent, ha, tk, and vgf genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction with Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) (6,8,9). Amplicons were cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega). Three clones were sequenced 3 times in both orientations by the dideoxy method, using M13 universal primers and ET Dynamic Terminator for MegaBACE (GE Healthcare, Fairfield, CT, USA). The nucleotide (nt) sequences of ha, tk, and vgf were assembled by using the CAP3 Sequence Assembling Program (10) and deposited in GenBank under accession numbers DQ070848, DQ085461, and DQ085462, respectively. The sequences and inferred amino acid sequences were aligned with those of orthopoxviruses by using the ClustalW 1.6 program (11).

PSTV ha gene sequence was compared to those of ARAV, Cantagalo virus (CTGV) (1,2), VACV-WR, CPXV-BR, VACV Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (VACV-IOC), and VACV Lister (VACV-LST). VACV-IOC and VACV-LST are vaccine strains used in the Brazilian smallpox eradication program (2,6). The PSTV ha gene sequences presented the same 18-nt deletion found in ARAV, CTGV, and VACV-IOC and shared more similarities to ARAV and CTGV homologous sequences. Additionally, 8 amino acid substitutions were unique to PSTV, ARAV, and CTGV. Since this characteristic was not observed in the vaccine strains, an independent origin is suggested. Moreover, PSTV HA differs from that of ARAV and CTGV by 1 and 2 amino acid substitutions, respectively (online Appendix Figure 4; available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/ EID/vol11no12/05-0773_app4.htm). The percentage of identity between ha, tk, and vgf nucleotide sequences and inferred amino acid sequences of PSTV with CPXV-BR and other VACV strains are presented in the Table. For the tk gene that is highly conserved among VACV, the PSTV nucleotide sequence had 100% identity to ARAV, VACV-LST, and VACV-WR homologous sequences. Additionally, PSTV vgf gene had a 3-nt deletion, corresponding to nt 7,669-7,671 of VACV-WR, causing the loss of 1 isoleucine in a stretch of 4 found in the ARAV and VACV-WR VGF sequences (Appendix Figure 4). PSTV VGF also exhibited 2 amino acid substitutions when compared to ARAV VGF sequences.

[FIGURE 4 OMITTED]

The alignments were used to construct phylogenetic trees by the neighbor-joining method using the Tamura Nei model implemented in MEGA3 (12). Trees were rooted at midpoint, and 1,000 bootstrap replications were performed. A tk and vgf genes concatenated phylogenetic tree was constructed by placing PSTV together with VACV strains (data not shown). Regarding ha sequences, PSTV was clustered to ARAV and CTGV (Figure 2).

Conclusions

The phylogenetic tree analysis suggested a strong phylogenetic relationship between PSTV and other Brazilian VACV strains. However, the vgf and ha gene analysis of PSTV, ARAV, and CTGV indicated that genetic heterogeneity exists among these viruses, which suggests that the ha gene deletion found in PSTV, ARAV, CTGV, and VACV-IOC could be a signature of New World or Brazilian VACV strains.

Additionally, that RFLP analysis showed a pattern identical with other Brazilian strains, similar to VACV-WR and different from CPXV, suggests that a cladogenesis event may have occurred. This conclusion is feasible considering that these viruses could be circulating in the wild since smallpox vaccination or even before, going back to the colonization of South America, when cattle and other animals were brought to the New World without quarantine or inspection. The VACV variants buffalopox and rabbitpox have originated from VACV subspeciation (13).

That humans were also infected and that these persons were all milkers, phenomena that had been observed during other Brazilian VACV outbreaks, points to an occupational zoonosis. Although parapoxvirus infection has been placed in the category of occupational zoonosis, to our knowledge no other orthopoxviruses have been reported to cause an occupational hazard. Economic losses are also a matter of concern. In addition to the reduction in milk production, extra veterinary costs are due to the usual occurrence of secondary infections on cows' teats leading to mastitis. The reduction in milk production is a concern because Brazil is a major milk exporter. Therefore, the spread of these viruses could severely impact the country's economy. In this regard, the clinical features, widespread dissemination, and epidemiology of the etiologic agent of these outbreaks must be understood.

Since 1963, all Brazilian orthopoxvirus isolates have been characterized as VACV strains (3,6,14,15). The growing geographic distribution of these outbreaks (Figure 3) indicates that these viruses may be emerging as zoonotic pathogens of cattle. This fact is especially important because a growing human population has no vaccine-derived immunity to smallpox or other orthopoxviruses. This situation could create an opportunity for these viruses to disseminate in Brazil. In addition, the isolation of another VACV strain strengthens the hypothesis that VACV is circulating in the New World and that these viruses seem to be endemic of this region.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela S. Lopes, Ilda M.V. Gama, Daniela Lemos, and colleagues from the Laboratory of Virus for their excellent technical support and C. Jungwirth for providing VACV-WR and CPXV-BR used in this study. We also thank Rodrigo A.F. Redondo and Fabricio R. dos Santos for advice on the phylogenetic analysis, Olga Pfeilsticker for technical assistance on electron microscopy, and Denise Golgher for English review.

Financial support was provided by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico (CNPq), Coordenacao de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior (CAPES), and Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG). B.P. Drumond, G.S. Trindade, J.M.S. Ferreira, J.A. Leite, and M.I.M.C. Guedes received fellowships from CNPq or CAPES. C.A. Bonjardim, E.G. Kroon, F.G. da Fonseca, P.C.P. Ferreira and Z.I.P. Lobato are recipients of research fellowships from CNPq.

References

(1.) de Souza Trindade G, da Fonseca FG, Marques JT, Nogueira ML, Mendes LC, Borges AS, et al. Aracatuba virus: a vaccinia like virus associated with infection in humans and cattle. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003 ;9:155-60.

(2.) Damaso CR, Esposito JJ, Condit RC, Moussatche N. An emergent poxvirus from humans and cattle in Rio de Janeiro State: Cantagalo virus may derive from Brazilian smallpox vaccine. Virology. 2000;277:439-49.

(3.) Nagasse-Sugahara TK, Kisielius JJ, Ueda-Ito M, Curti SP, Figueiredo CA, Cruz AS, et al. Human vaccinia-like virus outbreaks in Sao Paulo and Goias States, Brazil: virus detection, isolation and identification. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2004;46:315-22.

(4.) Morellato PC, Haddad CFB. The Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Biotropica. 2000; 32(4b Atlantic Forest Special Issue):786-92.

(5.) Crouch AC, Baxby D, McCracken CM, Gaskell RM, Bennett M. Serological evidence for the reservoir hosts of cowpox virus in British wildlife. Epidemiol Infect. 1995; 115:185-91.

(6.) Fonseca FG, Lanna MC, Campos MAS, Kitajima EW, Peres JN, Golgher RR, et al. Morphological and molecular characterization of the poxvirus BeAn 58058. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1171-86.

(7.) Meyer H, Ropp SL, Esposito JJ. Gene for A-type inclusion body protein is useful for a polymerase chain reaction assay to differentiate orthopoxviruses. J Virol Methods. 1997;64:217-21.

(8.) da Fonseca FG; Silva RL, Marques JT, Ferreira PC, Kroon EG. The genome of cowpox virus contains a gene related to those encoding the epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha and vaccinia growth factor. Virus Genes. 1999;18:151-60.

(9.) Ropp SL, Jin Q, Knight JC, Massung RF, Esposito JJ. PCR strategy for identification and differentiation of smallpox and other orthopoxviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2069-76.

(10.) CAP3 Sequence Assembling Program. [accessed 18-22 Apr 2005]. Available from http://deepe2.zool.iastate.edu/aat/ecap/cap.html

(11.) Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673-80.

(12.) Kumar S., Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:15-163.

(13.) The Universal Virus Database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Orthopoxvirus. [accessed 2 May 2005]. Available from http://www.ictvdb.rothamsted.ac.uk/ICTVdB/ 58110000.htm

(14.) da Fonseca FG, Trindade GS, Silva RL, Bonjardim CA, Ferreira PC, Kroon EG. Characterization of a vaccinia-like virus isolated in a Brazilian forest. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:223-8.

(15.) Trindade GS, da Fonseca FG, Marques JT, Diniz S, Leite JA, De Bodt S, et al. Belo Horizonte virus: a vaccinia-like virus lacking the A-type inclusion body gene isolated from infected mice. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2015-21.

Juliana A. Leite, * Betania P. Drumond, * Giliane S. Trindade, * Zelia I.P. Lobato, * Flavio G. da Fonseca, ([dagger]) Joao R. dos Santos, * Marieta C. Madureira, ([double dagger]) Maria I.M.C. Guedes, * Jaqueline M.S. Ferreira, * Claudio A. Bonjardim, Paulo C.P. Ferreira, * and Erna G. Kroon *

* Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil; ([dagger]) Centro de Pesquisas Rene Rachou-Fundacao Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil; and ([double dagger]) Instituto Mineiro de Agropecuaria, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. Brazil

Address for correspondence: Erna G. Kroon, Laboratorio de Virus, Departamento de Microbiologia, Instituto de Ciencias Biologicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Av. Antonio Carlos, 6627, Caixa Postal 486, CEP: 31270-901, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil; fax: 55-31-3443-6482; email: kroone@icb.ufmg.br

Ms Leite is a doctoral candidate at the Laboratory of Virus, Institute of Biological Sciences, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte-MG, Brazil. Her areas of research interest include virology, emergent viruses, molecular biology, and epidemiology.

COPYRIGHT 2005 U.S. National Center for Infectious Diseases

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group