Pertussis was a common childhood illness before routine immunization. Although immunization is now commonplace, the annual number of infections has increased in recent years. The diagnosis of pertussis is difficult in adolescents and adults because the typical syndrome of "whooping cough" may be absent. Prolonged cough may be the only feature, and physicians often do not consider pertussis when evaluating a coughing patient. Hewlett and Edwards reviewed the evaluation and treatment of adult pertussis.

The typical illness pattern begins with symptoms such as scratchy throat; rhinorrhea; eye irritation; and, possibly, a mild cough. After about one week, the paroxysmal coughing phase begins. This phase wanes after several weeks, but coughing may relapse and remit for weeks to months because of relapses from other upper respiratory infections. Symptoms in immunized adults are usually different from those in children. Paroxysmal coughing and sweating typically are present, and about one third of patients have pharyngeal symptoms. Most adults diagnosed with pertussis have had a cough for at least three weeks, and the cough persists for at least three months in about one fourth of patients.

Diagnosis requires clinical suspicion and a clear sense of symptom evolution because confirmatory testing relies on appropriate timing. Nasopharyngeal culture is the preferred diagnostic test, but Bordetella pertussis is difficult to grow. This method is recommended for patients presenting within three weeks of the onset of cough. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is more sensitive, but false-positive results may occur. Thus, PCR testing should be used in conjunction with culture when cough has been present for less than three weeks or when any symptoms have been present for four weeks. Antibody testing can involve acute and convalescent titers. Because pertussis usually is not in the differential early in the disease course, a titer obtained three weeks after the onset of cough may be confirmatory; however, the lack of widely available, rapid, and reliable tests limits this approach. Therefore, a combined approach is recommended. Early in the disease course, physicians should obtain a culture and perform PCR testing. From weeks three to four, PCR testing and serology should be performed; after four weeks, serology should be performed.

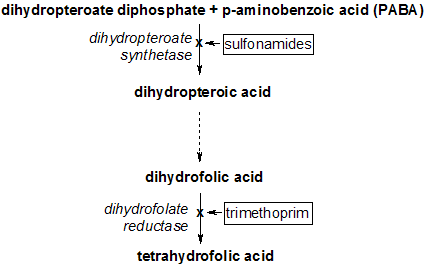

Treatment is unlikely to be beneficial for patients who have had symptoms for longer than one week. However, treatment may reduce the chance of disease transmission. Furthermore, organisms may be present up to three weeks after cough begins. Thus, treatment during the first four weeks of illness may provide benefit. Erythromycin is the preferred therapy; alternatives include azithromycin (Zithromax), clarithromycin (Biaxin), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra). These antibiotics also are used for contact prophylaxis.

The authors conclude that immunization against pertussis does not lead to lifelong immunity. Thus, many countries recommend an adolescent acellular pertussis booster. The United States is considering a similar addition.

Hewlett EL, Edwards KM. Pertussis--not just for kids. N Engl J Med March 24, 2005;352:1215-22.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Besides reminding us to consider pertussis in adults with persistent cough, this article also offers a glimpse of what may be the next addition to the adolescent or adult immunization schedule. The definitive immunization resource is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Immunization Program Web site (http://www.cdc.gov/nip). Another resource is Shots 2005, offered by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (http://www.immunizationed.org).--C.C.

CHUCK CARTER, M.D.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2006 Gale Group