Most uncomplicated urinary tract infections occur in women who are sexually active, with far fewer cases occurring in older women, those who are pregnant, and in men. Although the incidence of urinary tract infection has not changed substantially over the last 10 years, the diagnostic criteria, bacterial resistance patterns, and recommended treatment have changed. Escherichia coli is the leading cause of urinary tract infections, followed by Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been the standard therapy for urinary tract infection; however, E. coli is becoming increasingly resistant to medications. Many experts support using ciprofloxacin as an alternative and, in some cases, as the preferred first-line agent. However, others caution that widespread use of ciprofloxacin will promote increased resistance.

**********

Uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common diagnoses in the United States. In 1997, an estimated 8.3 million physician office visits were attributed to acute cystitis. (1) A U.S. and Canadian study showed that approximately one half of all women will have a UTI in their lifetimes, and one fourth will have recurrent infections. (2) The health care costs associated with UTIs exceed 1 billion dollars (3,4); therefore, any advance in the diagnosis and treatment of this entity could have a major economic impact. Streamlining the diagnostic process could also decrease morbidity and improve patient outcomes and satisfaction.

Epidemiology

Escherichia coli is the most common cause of uncomplicated UTI and accounts for approximately 75 to 95 percent of all infections. (2-5) A longitudinal study (6) of 235 women with 1,018 UTIs found that E. coli was the only causative agent in 69.3 percent of cases and was a contributing agent in an additional 2.4 percent of cases. Staphylococcus saprophyticus is a distant second, accounting for only 5 to 20 percent of infections. Other Enterobacteriaceae, such as Klebsiella and Proteus, occasionally cause UTI. (2,3,5) Although S. saprophyticus is less common than E. coli, it is more aggressive. Approximately one half of patients infected with S. saprophyticus present with upper urinary tract involvement, and these patients are more likely to have recurrent infection. (3)

Diagnosis

Uncomplicated UTI occurs in patients who have a normal, unobstructed genitourinary tract, who have no history of recent instrumentation, and whose symptoms are confined to the lower urinary tract. Uncomplicated UTIs are most common in young, sexually active women. Patients usually present with dysuria, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and/or suprapubic pain. Fever or costovertebral angle tenderness indicates upper urinary tract involvement. Studies show that no laboratory tests, including urinalysis and culture, can predict clinical outcomes in women 18 to 70 years of age who present with acute dysuria or urgency. (7) Dipstick urinalysis, however, is a widely used diagnostic tool. A dipstick urinalysis positive for leukocyte esterase and/or nitrites in a midstream-void specimen reinforces the clinical diagnosis of UTI. Leukocyte esterase is specific (94 to 98 percent) and reliably sensitive (75 to 96 percent) for detecting uropathogens equivalent to 100,000 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL of urine. (5) Nitrite tests may be negative if the causative organism is not nitrate-reducing (e.g., enterococci, S. saprophyticus, Acinetobacter). Therefore, the sensitivity of nitrite tests ranges from 35 to 85 percent, but the specificity is 95 percent. (8) Nitrite tests can also be false negative if the urine specimen is too diluted. (3) Microscopic hematuria may be present in 40 to 60 percent of patients with UTI. (3)

Routine urine cultures are not necessary because of the predictable nature of the causative bacteria. However, urinalysis may be appropriate for patients who fail initial treatment. Current literature suggests that a colony count of 100 CFU per mL has a sensitivity of 95 percent and a specificity of 85 percent, (3) but the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends using a colony count of 1,000 CFU per mL (80 percent sensitivity and 90 percent specificity) for symptomatic patients. (3,5) A cutoff of 100,000 CFU per mL defines asymptomatic bacteriuria. Physicians may have to request that sensitivities be performed on low-count bacteria if low counts are not the standard in their community.

After reviewing existing data on uncomplicated cystitis, the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound implemented evidence-based guidelines for treating adult women with acute dysuria or urgency. (7) These guidelines support treating women based on symptoms alone after phone triage by a nurse. These guidelines have reduced doctor visits and laboratory tests without increasing adverse outcomes. (7) A study (9) of these guidelines found that women treated by telephone triage had a 95 percent satisfaction rate. The study also found that if these guidelines were used for 147,000 women ages 18 to 55 years who were enrolled in the plan, it could save an estimated $367,000 annually. (9) A much smaller study (10) comparing telephone triage with office visits for treating symptomatic cystitis showed no difference in symptom improvement scores or overall patient satisfaction.

Treatment

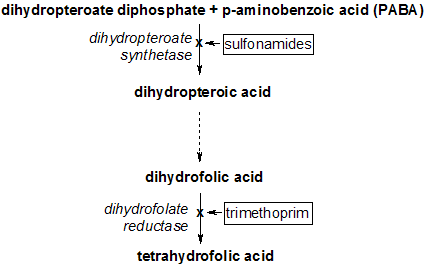

Many studies in the last decade have focused on the treatment length of standard therapies. A study (11) comparing a three-day course of ciprofloxacin (Cipro) 100 mg twice daily, ofloxacin (Floxin) 200 mg twice daily, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX; Bactrim, Septra) 160/800 mg twice daily, found that all three had comparable efficacy in managing uncomplicated UTI. Another study (12) comparing a short course (three days) of ciprofloxacin (100 mg twice daily) with the more traditional seven-day course of TMP-SMX (160/800 mg twice daily), and nitrofurantoin (Furadantin) (100 mg twice daily) found that ciprofloxacin had superior bacteriologic eradication rates after short-term follow-up (four to six weeks). All three medications had similar eradication rates immediately after therapy. (12) The study (12) also found that treatment failures associated with nitrofurantoin were more common in nonwhite women older than 30 years, but researchers were unable to account for this difference.

E. coli's resistance to TMP-SMX is an increasing problem across the United States. (13) A recent article (14) that reviewed data from The Surveillance Network (TSN) database reported that E. coli had an overall resistance rate of 38 percent to ampicillin, 17.0 percent to TMP-SMX, 0.8 percent to nitrofurantoin, and 1.9 to 2.5 percent to fluoroquinolones. The article (14) also reported that E. coli strains resistant to TMP-SMX had a 9.5 percent rate of concurrent ciprofloxacin resistance versus a 1.9 percent rate of concurrent resistance to nitrofurantoin. Another review (15) of data from TSN (January through September 2000) found that 56 percent of E. coli isolates were susceptible to all tested drugs including ampicillin, cephalothin (Keflin), nitrofurantoin, TMP-SMX, and ciprofloxacin. Among the tested antimicrobials, E. coli had the highest resistance rate to ampicillin (39.1 percent), followed by TMP-SMX (18.6 percent), cephalothin (15.6 percent), ciprofloxacin (3.7 percent), and nitrofurantoin (1.0 percent). (15) Resistance rates varied by region of the country. Of the more than 38,000 isolates, 7.1 percent had a multidrug resistance. (15) A 1999 regional analysis (16) of the United States showed that resistance to TMP-SMX was highest in the Western-Southern-Central regions, with a 23.9 percent resistance rate. The Pacific and Mountain regions had a 21.8 percent resistance rate, and the South Atlantic region had a 19.7 percent resistance rate. (16) Resistance rates in southern Europe, Israel, and Bangladesh reportedly have been as high as 30 to 50 percent. (4)

Fluoroquinolones have become popular treatments for patients with uncomplicated UTI because of E. coli's emerging resistance to other common medications. The reported resistance rate of E. coli to ciprofloxacin is still very low at less than 3 percent. (13) The IDSA guidelines recommend the use of fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, fleroxacin [not available in the United States], norfloxacin [Noroxin], and ofloxacin) as first-line agents in communities with greater than 10 to 20 percent resistance rates to TMPSMX. 17 An economic analysis (4) found that a three-day regimen of ciprofloxacin was more cost-effective than a three-day regimen of TMP-SMX if the resistance rate to that drug was 19.0 percent or greater. (4) A study (13) comparing the newest formulation of extendedrelease ciprofloxacin (500 mg daily for three days) with traditional ciprofloxacin (250 mg twice daily for three days) showed equivalent clinical cure rates. A 1995 study (18) comparing multidose regimens of ciprofloxacin showed that the minimal effective dosage was 100 mg twice daily. Another study (19) compared a single 400-mg dose of gatifloxacin (Tequin), with three-day regimens of gatif loxacin (200 mg twice daily) and ciprof loxacin (100 mg twice daily). The single-dose therapy had a clinical response rate equivalent to the two three-day regimens. Gatifloxacin is also expected to be 1,000 times less likely than older fluoroquinolones to become resistant because of its 8-methoxy structure. (19)

Fosfomycin (Monurol) is another treatment option for patients with UTI. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indicates fosfomycin for the treatment of women with uncomplicated UTI. A study (20) comparing a single dose of fosfomycin (3 g) with a seven-day course of nitrofurantoin (100 mg twice daily) showed similar bacteriologic cure rates (60 versus 59 percent, respectively). (20) Fosfomycin is bactericidal and concentrates in the urine to inhibit the growth of pathogens for 24 to 36 hours. (20) When fosfomycin entered the market in 1997, unpublished studies submitted to the FDA found that it was significantly less effective in eradicating bacteria than seven days of ciprofloxacin or 10 days of TMP-SMX (63 percent, 89 percent, and 87 percent eradication rates, respectively). (21)

Cephalosporins, including cephalexin (Keflex), cefuroxime (Ceftin), and cefixime (Suprax), can also manage UTIs. Increasing resistance, however, has limited their effectiveness. (2) The broad spectrum of this class also increases the risk of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Cephalosporins are pregnancy category B drugs, and a seven-day regimen can be considered as a second-line therapy for pregnant women. (2) Table 1 summarizes the possible treatments in patients with UTI.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES

Physicians commonly recommend nonpharmacologic options (e.g., drinking cranberry juice or water) to patients with cystitis. A Cochrane review (22) found insufficient evidence to recommend the use of cranberry juice to manage UTI.

Similarly, no scientific evidence suggests that women with cystitis should increase their fluid intake, and some doctors speculate that increased fluid may be detrimental because it may decrease the urinary concentration of antimicrobial agents. (17)

OLDER WOMEN

Treating older women who have UTIs requires special consideration. A recent study (23) compared a 10-day course of ciprofloxacin (250 mg twice daily) with a 10-day course of TMP-SMX (160/800 mg twice daily). The study, which included 261 outpatient and institutionalized women with an average age of approximately 80 years, showed a 96 percent bacteriologic eradication rate with ciprofloxacin compared with an 80 percent eradication rate with TMP-SMX for the three most common isolates. (23) Although the IDSA did not study postmenopausal women specifically, its review found that evidence supports the use of a seven-day antibiotic regimen for older women. The three-day therapy had a higher failure rate when compared with the seven-day regimen. (24) A Cochrane review (25) found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against short- versus long-term (seven to 10 days) treatment of uncomplicated UTIs in older women.

MEN

The incidence of UTI in men ages 15 to 50 years is very low, and little evidence exists on treating them. Risk factors include homosexuality, intercourse with an infected woman, and lack of circumcision. The limited available data are similar on two key points. First, the data show that men should receive the same treatment as women with the exception of nitrofurantoin, which has poor tissue penetration. (17) Second, a minimum of seven days is the recommended treatment length, because the likelihood of complicating factors is higher than in women. (5,17)

Recommendations

After reviewing the available clinical data as of 1999 and classifying it by quality of evidence, the IDSA published guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents to treat women with UTI. (24) The American Urological Association and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases have endorsed these guidelines, (2,17) which can be summarized into four main recommendations. First, the IDSA recommends a three-day course of double-strength TMPSMX as empiric therapy in areas where E. coli resistance rates are below 20 percent. Second, although it recognizes that they have efficacy rates similar to TMP-SMX, the IDSA does not recommend fluoroquinolones as universal first-line agents because of resistance concerns. Third, the IDSA recommends a seven-day course of nitrofurantoin or a single dose of fosfomycin as reasonable treatment alternatives. Finally, the IDSA does not recommend the use of beta-lactams because multiple studies have shown them to be inferior when compared with other treatments. (23)

Figure 1 is an algorithm for the management of uncomplicated UTIs.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

The author thanks Karen Malnar, R.N., C.C.R.C., and Dana Carroll, Pharm.D., for assisting her with this article.

REFERENCES

(1.) National Institutes of Health. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NKUDIC). Accessed online May 4, 2005, at: http://kidney.niddk. nih.gov.

(2.) Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infection: traditional pharmacologic therapies. Dis Mon 2003;49:111-28.

(3.) Faro S, Fenner DE. Urinary tract infections. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1998;41:744-54.

(4.) Perfetto EM, Gondek K. Escherichia coli resistance in uncomplicated urinary tract infection: a model for determining when to change first-line empirical antibiotic choice. Manag Care Interface 2002;15:35-42.

(5.) Hooton TM, Stamm WE. Diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1997;11:551-81.

(6.) Vosti KL. Infections of the urinary tract in women: a prospective, longitudinal study of 235 women observed for 1-19 years. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:369-87.

(7.) Stuart ME, Macuiba J, Heidrich F, Farrell RG, Braddick M, Etchison S. Successful implementation of an evidence-based clinical practice guideline: acute dysuria/ urgency in adult women. HMO Pract 1997;11:150-7.

(8.) Orenstein R, Wong ES. Urinary tract infections in adults. Am Fam Physician 1999;59:1225-34, 1237.

(9.) Saint S, Scholes D, Fihn SD, Farrell RG, Stamm WE. The effectiveness of a clinical practice guideline for the management of presumed uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. Am J Med 1999;106:636-41.

(10.) Barry HC, Hickner J, Ebell MH, Ettenhofer T. A randomized controlled trial of telephone management of suspected urinary tract infections in women. J Fam Pract 2001;50:589-94.

(11.) McCarty JM, Richard G, Huck W, Tucker RM, Tosiello RL, Shan M, et al.; for the Ciprofloxacin Urinary Tract Infection Group. A randomized trial of short-course ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, or trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole for the treatment of acute urinary tract infection in women. Am J Med 1999;106:292-9.

(12.) Iravani A, Klimberg I, Briefer C, Munera C, Kowalsky SF, Echols RM. A trial comparing low-dose, short-course ciprofloxacin and standard 7 day therapy with co-trimoxazole or nitrofurantoin in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 1999;43(suppl A):S67-75.

(13.) Henry DC Jr, Bettis RB, Riffer E, Haverstock DC, Kowalsky SF, Manning K, et al. Comparison of oncedaily extended-release ciprofloxacin and conventional twice-daily ciprofloxacin for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. Clin Ther 2002;24:2088-104.

(14.) Karlowsky JA, Thornsberry C, Jones ME, Sahm DF. Susceptibility of antimicrobial-resistant urinary Escherichia coli isolates to fluoroquinolones and nitrofurantoin. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:183-7.

(15.) Sahm DF, Thornsberry C, Mayfield DC, Jones ME, Karlowsky JA. Multidrug-resistant urinary tract isolates of Escherichia coli: prevalence and patient demographics in the United States in 2000. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001;45:1402-6.

(16.) Seifert R, Weinstein DM, Li-McLeod J. National prevalence of Escherichia coli resistance to trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole: managed care implications in the treatment of urinary tract infections. J Manag Care Pharm 2001;7:132. Accessed online May 4, 2005, at: http://www.amcp.org/data/jmcp/jmcp_2001_7_2.pdf.

(17.) Naber KG. Treatment options for acute uncomplicated cystitis in adults. J Antimicrob Chemother 2000;46(suppl 1):S23-7.

(18.) Iravani A, Tice AD, McCarty J, Sikes DH, Nolen T, Gallis HA, et al., for the Urinary Tract Infection Study Group. Short-course ciprofloxacin treatment of acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. The minimum effective dose [published correction appears in Arch Intern Med 1995;155:871]. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:485-94.

(19.) Richard GA, Mathew CP, Kirstein JM, Orchard D, Yang JY. Single-dose fluoroquinolone therapy of acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial comparing single-dose to 3-day fluoroquinolone regimens. Urology 2002;59:334-9.

(20.) Stein GE. Comparison of single-dose fosfomycin and a 7-day course of nitrofurantoin in female patients with uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Clin Ther 1999;21:1864-72.

(21.) Fosfomycin for urinary tract infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther 1997;39:66-8.

(22.) Jepson RG, Mihaljevic L, Craig J. Cranberries for treating urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001322.

(23.) Gomolin IH, Siami PF, Reuning-Scherer J, Haverstock DC, Heyd A, for the Oral Suspension Study Group. Efficacy and safety of ciprofloxacin oral suspension versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole oral suspension for treatment of older women with acute urinary tract infection. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1606-13.

(24.) Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, Johnson JR, Schaeffer AJ, Stamm WE. Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Clin Infect Dis 1999;29:745-58.

(25.) Lutters M, Vogt N. Antibiotic duration for treating uncomplicated, symptomatic lower urinary tract infections in elderly women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD001535.

SUSAN A. MEHNERT-KAY, M.D., is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine-Tulsa. She received her medical degree at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine-Tulsa, where she also completed a family medicine residency.

Address correspondence to Susan A. Mehnert-Kay, M.D., 1111 S. St. Louis Ave., Tulsa, OK 74120. (e-mail: Susan-mehnert@ouhsc.edu). Reprints are not available from the author.

Members of various family medicine departments develop articles for "Practical Therapeutics." This article is one in a series coordinated by the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, Tulsa, Okla. Coordinator of the series is John Tipton, M.D.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group