Bacteria are responsible for approximately 5 to 10 percent of pharyngitis cases, with group A beta-hemolytic streptococci being the most common bacterial etiology. A positive rapid antigen detection test may be considered definitive evidence for treatment; a negative test should be followed by a confirmatory throat culture when streptococcal pharyngitis is strongly suspected. Treatment goals include prevention of suppurative and nonsuppurative complications, abatement of clinical signs and symptoms, reduction of bacterial transmission and minimization of antimicrobial adverse effects. Antibiotic selection requires consideration of patients' allergies, bacteriologic and clinical efficacy, frequency of administration, duration of therapy, potential side effects, compliance and cost. Oral penicillin remains the drug of choice in most clinical situations, although the more expensive cephalosporins and, perhaps, amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium provide superior bacteriologic and clinical cure rates. Alternative treatments must be used in patients with penicillin allergy, compliance issues or penicillin treatment failure. Patients who do not respond to initial treatment should be given an antimicrobial that is not inactivated by penicillinase-producing organisms (e.g., amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium, a cephalosporin or a macrolide). Patient education may help to reduce recurrence. (Am Fam Physician 2001;63:1557-64,1565.)

Every day, the family physician can expect to encounter at least one patient with a sore throat. Approximately 30 to 65 percent of pharyngitis cases are idiopathic, and 30 to 60 percent have a viral etiology (rhinovirus, adenovirus and many others).(1) Only 5 to 10 percent of sore throats are caused by bacteria, with group A beta-hemolytic streptococci being the most common bacterial etiology.(1) Other bacteria that occasionally cause pharyngitis include groups C and G streptococci, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Arcanobacterium haemolyticus.(2)

Pharyngitis caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, commonly called "strep throat" or streptococcal pharyngitis, has an incubation period of two to five days and is most common in children five to 12 years of age. The illness can occur in clusters and is diagnosed most often in the winter and spring.

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci are ordinarily spread by direct person-to-person contact, most likely through droplets of saliva or nasal secretions.(3) Crowding increases transmission, and outbreaks of streptococcal pharyngitis are common in institutional settings, the military, schools and families. Outbreaks resulting from human contamination of food during preparation have also been reported.(4)

Clinical Presentation

The textbook case of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis is an acute illness with a predominant sore throat and a temperature higher than 38.5[degrees]C (101.3[degrees]F). Constitutional symptoms include fever and chills, myalgias, headaches and nausea. Physical findings may include petechiae of the palate, pharyngeal and tonsillar erythema and exudates, and anterior cervical adenopathy. However, many patients do not fit the textbook picture. Children, for example, may present with abdominal pain or emesis.

Patients with other respiratory complaints, such as cough or coryza, are less likely to have streptococcal pharyngitis.(5,6) A sandpaper-like rash on the trunk, which is sometimes linear on the groin and axilla (Pastia's lines), is more consistent with scarlet fever.

Diagnostic Testing

Throat culture remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis. Under ideal conditions, the sensitivity of throat culture for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci is 90 percent; in office settings, the sensitivity ranges from 29 to 90 percent. The specificity of throat culture is 99 percent under ideal conditions and can be anywhere from 76 to 99 percent in office settings.(5)

A rapid antigen detection test (rapid strep test) may be performed in the office setting, with results available in five to 10 minutes. This test has a reported specificity of greater than 95 percent but a sensitivity of only 76 to 87 percent.(2,5)

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics(4) and the American Heart Association,(7) a positive rapid antigen detection test may be considered definitive evidence for treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. A confirmatory throat culture should follow a negative rapid antigen detection test when the diagnosis of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection is strongly suspected.(4,7)

Investigators in one recent study(8) recommended that cost-conscious physicians use well-validated prediction rules to help them make better use of rapid antigen tests and throat cultures. Clinical prediction rules take into account key elements of a patient's history and physical examination and allow physicians to predict the probability of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis.

Therapeutic Goals

Treatment goals in patients with streptococcal pharyngitis, including the management of complications, are listed in Table 1.(5) Nonsuppurative and suppurative complications are listed in Table 2.(5)

TABLE 1

Treatment Goals in Patients with Group A Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Prevention of nonsuppurative and suppurative complications

Abatement of clinical signs and symptoms

Reduction of bacterial transmission to close contacts

Minimization of adverse effects of antimicrobial therapy

Information from Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: a practice guideline. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:574-83.

TABLE 2

Complications of Group A Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Nonsuppurative complications

Rheumatic fever

Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis

Suppurative complications

Cervical lymphadenitis

Peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess

Sinusitis

Mastoiditis

Otitis media

Meningitis

Bacteremia

Endocarditis

Pneumonia

Information from Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: a practice guideline. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:574-83.

Acute rheumatic fever and poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis are the nonsuppurative complications of streptococcal pharyngitis. During World War II, the incidence of acute rheumatic fever was as high as 388 cases per 100,000 U.S. Army personnel. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the incidence of this illness fell to 0.23 to 1.14 cases per 100,000 school-aged children,(9) most likely because of changes in nutrition, decreased crowding, alterations in the pathogen's immune-stimulating potential, improved access to medical care and the introduction of effective antibiotics. However, important outbreaks of acute rheumatic fever in the late 1980s raised concern that virulent serotypes were on the rise.(9,10) The reported annual incidence of acute rheumatic fever is now approximately one case per 1 million population.(8)

Suppurative complications of streptococcal pharyngitis occur as infection spreads from pharyngeal mucosa to deeper tissues. Since the mid-1980s, an increase in the severity of streptococcal pharyngitis cases has been reported in the United States.(9,10)

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci can also cause invasive infections such as necrotizing fasciitis, myositis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Although the skin is the most common portal of entry for these invasive infections, the pharynx has been documented as the point of entry in some cases.(9,11)

Antibiotic Therapy

Multiple factors should be considered in selecting an antibiotic to treat streptococcal pharyngitis (Table 3).(5) Potential antibiotic regimens are provided in Table 4. An algorithm for the suggested evaluation and treatment of patients with a sore throat is provided in Figure 1.(12)

TABLE 3

Factors in Selecting an Antibiotic for Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Bacteriologic and clinical efficacy

Patient allergies

Compliance issues

Frequency of administration

Palatability

Cost

Spectrum of activity

Potential side effects

Information from Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: a practice guideline. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:574-83.

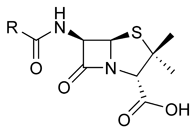

PENICILLIN

For almost five decades, penicillin has been the drug of choice for the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. This antibiotic has proven efficacy and safety, a narrow spectrum of activity and low cost.

From the early 1950s into the 1970s, streptococcal pharyngitis was treated with a single intramuscular injection of penicillin G benzathine. Studies from the late 1960s and the 1970s revealed that streptococcal eradication was equal with intramuscularly and orally administered penicillins. Thus, since the early 1980s, oral treatment using penicillin V has been preferred.(13)

Although penicillin is effective, it does have drawbacks. About 10 percent of patients are allergic to penicillin, and compliance with a four-times-daily dosing schedule is difficult. Fortunately, cure rates are similar for 250 mg of penicillin V given two, three or four times daily.(14) The use of intramuscularly administered penicillin may overcome compliance problems, but the injection is painful.(14)

Bacteriologic and clinical treatment failures occur with penicillin, as with all antibiotics. "Bacteriologic failure" is failure to eradicate the streptococcal organism responsible for the original infection. Patients with this type of treatment failure may or may not remain symptomatic. Some infected but asymptomatic patients may be carriers. Patients who remain symptomatic despite treatment are considered "clinical failures" and must be retreated. Studies conducted over the past 40 years have reported penicillin V bacteriologic failure rates ranging from 10 to 30 percent and clinical failure rates ranging from 5 to 15 percent.(15)

ALTERNATIVES TO PENICILLIN

Amoxicillin. In children, the cure rates for amoxicillin given once daily for 10 days are similar to those for penicillin V.(16-18) The absorption of amoxicillin is unaffected by the ingestion of food, and the drug's serum half-life in children is longer than that of penicillin V.

Amoxicillin is less expensive and has a narrower spectrum of antimicrobial activity than the presently approved once-daily antibiotics. Suspensions of this drug taste better than penicillin V suspensions, and chewable tablets are available. However, gastrointestinal side effects and skin rash may be more common with amoxicillin.

Macrolides. Erythromycin is recommended as a first alternative in patients with penicillin allergy.(4,5,7) Because erythromycin estolate is hepatotoxic in adults, erythromycin ethylsuccinate may be used. Erythromycin is absorbed better when it is given with food. Although this antibiotic is as effective as penicillin, 15 to 20 percent of patients cannot tolerate its gastrointestinal side effects.(16)

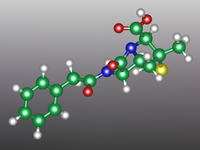

The extended spectrum of azithromycin (Zithromax) allows once-daily dosing and a shorter treatment course. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has labeled a five-day course of azithromycin as a second-line therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis. Azithromycin is associated with a low incidence of gastrointestinal side effects, and three- and four-day courses of this antibiotic have been shown to be as effective as a 10-day course of penicillin V.(19,20) However, azithromycin is expensive, and its effectiveness in preventing acute rheumatic fever is unknown.

Cephalosporins. A 10-day course of a cephalosporin has been shown to be superior to penicillin in eradicating group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. A meta-analysis(21) of 19 comparative trials found that the overall bacteriologic cure rate for cephalosporins was 92 percent, compared with 84 percent for penicillin (P [less than] 0.0001).

Cephalosporins have a broader spectrum of activity than penicillin V. Unlike penicillin, cephalosporins are resistant to degradation from beta-lactamase produced by copathogens. First-generation agents such as cefadroxil (Duricef) and cephalexin (Keflex, Keftab) are preferable to second- or third-generation agents, if used, because they offer a narrower spectrum of activity.(7)

Because of the possibility of cross-reactivity, patients with immediate hypersensitivity to penicillin should not be treated with a cephalosporin. Cephalosporins are also expensive. Therefore, use of these agents is often reserved for patients with relapse or recurrence of streptococcal pharyngitis.

Amoxicillin-Clavulanate Potassium. The combination drug amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium (Augmentin) is resistant to degradation from beta-lactamase produced by copathogens that may colonize the tonsillopharyngeal area. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is often used to treat recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis.(22) Its major adverse effect is diarrhea. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is also expensive.

MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Treatment Failure and Reinfection. A recent retrospective chart review(23) found that recurrent group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections were more common in the 1990s than in the 1970s. Within days after completing antimicrobial therapy, a small percentage of patients redevelop symptoms of acute pharyngitis, with the infection confirmed by laboratory tests. These patients have either relapse or reinfection. Theories to explain apparent treatment failures include lack of antibiotic compliance, repeat exposure, beta-lactamase-producing copathogens, eradication of protective pharyngeal microflora, antibiotic suppression of immunity and penicillin resistence.(15)

Not all treatment failures should be regarded in the same manner. Repeated episodes in a patient should prompt a search within the patient's family for an asymptomatic carrier who, if found, can be treated. Patients who do not comply with a 10-day course of penicillin should be offered an alternative, such as intramuscularly administered penicillin or a once-daily orally administered macrolide or cephalosporin. Patients with clinical failure should be treated with an antimicrobial agent that is not inactivated by penicillinase-producing organisms. Amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium, cephalosporins and macrolides fall into this category.

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci persist for up to 15 days on unrinsed toothbrushes and removable orthodontic appliances.(24) The pathogens are not isolated from rinsed toothbrushes after three days. Instructing patients to rinse toothbrushes and removable orthodontic appliances thoroughly may help to prevent recurrent infections.

Pets. Transmission of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci occurs principally through contact with respiratory secretions from an infected person. Although anecdotes are numerous and a few cases have been reported,(25) family pets are rare reservoirs of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.(5,9,26)

Close Contacts. During epidemics, 50 percent of the siblings and 20 percent of the parents of infected children develop streptococcal pharyngitis.(14) Asymptomatic contacts do not require cultures or prophylaxis. Symptomatic contacts may be treated with or without cultures.

Follow-up and Carriers. Routine post-treatment throat cultures are not necessary. About 5 to 12 percent of treated patients have a positive post-treatment culture, regardless of the therapy given.(27) A positive post-treatment culture represents the asymptomatic chronic carrier state, and carriers are not a significant source for the spread of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. Furthermore, they are not at risk of developing rheumatic fever.(14) In general, asymptomatic carriers are not treated unless they are associated with treatment failure in a close-contact index patient.

Contagion. Patients with streptococcal pharyngitis are considered contagious until they have been taking an antibiotic for 24 hours.(2) Children should not go back to their day-care center or school until their temperature returns to normal and they have had at least 24 hours of antibiotic therapy.

Streptococcal Necrotizing Fasciitis. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci are the causative organisms in streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis. This infection, attributed to so-called "flesh-eating bacteria," has been the subject of sensational journalistic reports. Invasive streptococcus strains usually have a cutaneous portal of entry and rarely enter via the tonsillopharyngeal area.(2,28,29) Patients with streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis may develop streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

Symptomatic Treatment. Antibiotic therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis shortens the duration of symptoms by less than one day.(30) Therefore, measures to relieve symptoms are important. Salt-water gargles, lozenges, aspirin-containing gum, demulcents and other remedies all have proponents. No evidence confirms or denies the utility of these measures.

Acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug may be given to reduce temperature. Children and adolescents should not take aspirin.

The Future

In time, rapid tests such as optical immunoassay and chemiluminescent DNA may increase the accuracy and, unfortunately, the cost of diagnosing group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections. Current research on a vaccine, involving the streptococcal M protein, may allow prevention of the disease.(31) However, the clinical studies that must follow basic research on a vaccine will require many years. A marker to identify susceptibility to rheumatic fever may make use of the vaccine in susceptible persons practical.(4)

More research on penicillin treatment failures would be useful. If a reported increase in recurrences after antibiotic treatment(23) is confirmed elsewhere and streptococcal serotypes and drug sensitivities are, indeed, changing, penicillin will probably no longer be the drug of choice for the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis.

REFERENCES

(1.) Pichichero ME. Group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis: cost-effective diagnosis and treatment. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:390-403.

(2.) Pichichero ME. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections. Pediatr Rev 1998;19:291-302.

(3.) Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Denny FW. Management of healthcare workers with pharyngitis or suspected streptococcal infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996;17:753-61.

(4.) Pickering LK, ed. 2000 Red book: report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 25th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000:526-36.

(5.) Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: a practice guideline. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:574-83.

(6.) Perkins A. An approach to diagnosing the acute sore throat. Am Fam Physician 1997;55:131-8,141-2.

(7.) Dajani A, Taubert K, Ferrieri P, Peter G, Shulman S. Treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis and prevention of rheumatic fever: a statement for health professionals. Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the American Heart Association. Pediatrics 1995; 96(4 pt 1):758-64.

(8.) Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, Ives K, Carey M. Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA 2000; 284:2912-8.

(9.) Bronze MS, Dale JB. The reemergence of serious group A streptococcal infections and acute rheumatic fever. Am J Med Sci 1996;311:41-54.

(10.) Kaplan EL. Recent epidemiology of group A streptococcal infections in North America and abroad: an overview. Pediatrics 1996;97(6 pt 2):945-8.

(11.) Givner LB, Abramson JS, Wasilauskas B. Apparent increase in the incidence of invasive group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal disease in children. J Pediatr 1991;118:341-6.

(12.) Sloane PD, et al., eds. Essentials of family medicine. 3d ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1998:629.

(13.) Bass JW. Treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis revisited. JAMA 1986;256:740-3.

(14.) Bass JW. Antibiotic management of group A streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1991;10(10 suppl):S43-9.

(15.) Pichichero ME. Streptococcal pharyngitis: is penicillin still the right choice? Compr Ther 1996;22:782-7.

(16.) Feder HM, Gerber MA, Randolph MF, Stelmach PS, Kaplan EL. Once-daily therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis with amoxicillin. Pediatrics 1999;103: 47-51.

(17.) Gopichand I, Williams GD, Medendorp SV, Saracusa C, Sabella C, Lampe JB, et al. Randomized, single-blinded comparative study of the efficacy of amoxicillin (40 mg/kg/day) versus standard-dose penicillin V in the treatment of group A streptococcal pharyngitis in children. Clin Pediatr [Phila] 1998;37:341-6.

(18.) Shvartzman P, Tabenkin H, Rosentzwaig A, Dolginov F. Treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis with amoxycillin once a day. BMJ 1993;306:1170-2.

(19.) Hamill J. Multicentre evaluation of azithromycin and penicillin V in the treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis and tonsillitis in children. J Antimicrob Chemother 1993;31(suppl E):89-94.

(20.) Hooton TM. A comparison of azithromycin and penicillin V for the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Am J Med 1991;91(3A):23S-6.

(21.) Pichichero ME, Margolis PA. A comparison of cephalosporins and penicillins in the treatment of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis: a meta-analysis supporting the concept of microbial copathogenicity. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1991; 10:275-81.

(22.) Brook I. Treatment of patients with acute recurrent tonsillitis due to group A beta-haemolytic streptococci: a prospective randomized study comparing penicillin and amoxycillin/clavulanate potassium. J Antimicrob Chemother 1989;24:227-33.

(23.) Pichichero ME, Green JL, Francis AB, Marsocci SM, Murphy AM, Hoeger W, et al. Recurrent group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17:809-15.

(24.) Brook I, Gober AE. Persistence of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci in toothbrushes and removable orthodontic appliances following treatment of pharyngotonsillitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124:993-5.

(25.) Mayer G, Van Ore S. Recurrent pharyngitis in family of four. Household pet as reservoir of group A streptococci. Postgrad Med 1983;74(1):277-9.

(26.) Falck G. Group A streptococci in household pets' eyes--a source of infection in humans? Scand J Infect Dis 1997;29:469-71.

(27.) Pichichero ME, Marsocci SM, Murphy ML, Hoeger W, Green JL, Sorrento A. Incidence of streptococcal carriers in private pediatric practice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:624-8.

(28.) Bisno AL, Stevens DL. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med 1996;334: 240-5.

(29.) Brien JH, Bass JW. Streptococcal pharyngitis: optimal site for throat culture. J Pediatr 1985;106:781-3.

(30.) Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP, Spinks AB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2): CD000023.

(31.) Markowitz M. Pioneers and modern ideas. Rheumatic fever--a half-century perspective. Pediatrics 1998;102(1 pt 3):272-4.

Members of various medical faculties develop articles for "Practical Therapeutics." This article is one in a series coordinated by the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Medicine, Columbia, Mo. Guest editor of the series is Robert L. Blake, Jr., M.D.

CYNTHIA S. HAYES, M.D., M.H.A., is a resident in family medicine at the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Medicine, Columbia, Mo., where she also earned her medical degree and a master's degree in health administration.

HAROLD WILLIAMSON, JR., M.D., M.S.P.H., is chairman of the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Medicine. He earned his medical degree at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland. He then completed a family medicine residency at the University of Minnesota Medical School-Minneapolis and a Robert Wood Johnson academic family medicine fellowship at the University of Missouri-Columbia.

Address correspondence to Cynthia S. Hayes, M.D., M.H.A., Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri-Columbia School of Medicine, M228 Medical Sciences Building, Columbia, MO 65201 (e-mail: hayescs@health. missouri.edu). Reprints are not available from the authors.

COPYRIGHT 2001 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group