Sarah is a 3-year-old female who coughs during the evening, throughout the night, and in the early morning. When she gets a cold, her cough intensifies. Albert is a 14-year-old male who cannot complete a basketball game because he becomes winded and short of breath; he frequently coughs and vomits while playing. Anne is a 35-year-old female who has been hospitalized each September for the past three years, due to bronchitis. George is a 65-year-old male who wheezes every day and cannot walk up a flight of stairs without resting. What do these four individuals have in common? They all have asthma.

Asthma--an inflammatory disease of the bronchial tubes, the pipes that bring air from the nose and mouth into the lungs--affects some 15 million people in the United States alone. The disease is responsible for an estimated 100 million days of restricted activity each year and more than 5,000 deaths. Some 5 million children are asthmatic, making it the most common chronic childhood disease; it's also the number one cause of hospitalization and school absenteeism. The problem is especially severe in the inner cities, where the rates of asthma emergency room visits and deaths can be eight times the national average, in both children and adults.

Three things happen inside the bronchial tubes and airways in the lungs of people with asthma. The first change is inflammation: The tubes become red irritated, and swollen. This inflamed tissue "weeps," producing thick mucus. If the inflammation persists, it can lead to permanent thickening in the airways.

Next comes constriction: The muscles around the bronchial tubes tighten, causing the airways to narrow. This is called bronchospasm or bronchoconstriction.

Finally, there's hyperreactivity. The chronically inflamed and constricted airways be come highly reactive to so-called triggers; things like allergens (animal dander, dust mites, molds, pollens), irritants (tobacco smoke, strong odors, car and factory emissions), and infections (flu, the common cold). These triggers result in progressively more inflammation and constriction.

In most cases, asthma starts in early childhood--before the age of six--and is often linked to heavy exposure to dust mites and tobacco smoke. In very young children, however, viral infections are more likely to cause trouble than are allergens and irritants. In addition, researchers have identified a number of factors that seem to increase an individual's risk of developing asthma: having a genetic predisposition (in particular, having a mother with asthma); coming from a family with allergy problems such as atopic dermatitis (eczema), allergic rhinitis (hay fever), or allergen-induced asthma; and exposure to certain allergens, irritants, and infections at particularly vulnerable life periods.

It's important to realize that many of the symptoms of asthma can be subtle. For instance, one of the most common symptoms of asthma is a recurrent whistling or hissing sound as you breathe out, also known as wheezing. However, not everybody with asthma wheezes. The same is true for the other common symptoms of asthma, which include frequently feeling short of breath, especially when exercising, walking up a hill or up stairs; a repeated sensation of tightness in the chest; and a cough that lasts more than seven to ten days, or a cough that occurs after exercise or when you're exposed to cold, dry air. The cough is usually worse at night and early in the morning, and frequently interferes with sleep.

Today, physicians caring for individuals with asthma in the United States look to the recently revised and updated Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma, which were released by the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, under the direction of the National Institute of Health, and its National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The aim of the document is to improve the outcome for all individuals with asthma; understanding its recommendations will help physicians and patients get a better handle on the disease, its diagnosis, and its management. The four main components of the guidelines are as follows:

COMPONENT 1 Initial assessment and Diagnosis of Asthma

To establish a diagnosis of asthma--and to rule out other possibilities--a thorough history and physical examination are important. Asthma should be considered in a patient who has any of the symptoms listed earlier, especially if these symptoms occur or worsen with exercise, viral upper respiratory infections, exposure to allergens or irritants, changes in the weather, strong emotional expression, and--in women--changes in the menstrual cycle.

During the physical exam, the physician should measure the air flow through the bronchial tubes, using a device called a spirometer. This will allow the doctor to evaluate the amount of obstruction in the airway and, later, to document any improvement. Indeed, the report strongly recommends spirometry both at diagnosis and during periodic check ups for those who can perform the test (i.e., children over five a nd adults). After the diagnosis has been made, the patients themselves can monitor their condition by measuring their peak expiratory flow rate. The peak flow monitor is a simple machine which is less sophisticated and sensitive than the spirometer, but can be used in the home. However, while it is recommended that all individuals over five years of age with persistent asthma know how to perform peak flow monitoring and have the monitor available to them at home, regular testing isn't necessary for every asthmatic patient.

For those patients whose disease is not readily controlled and who have experienced severe episodes, referral to an asthma specialist is strongly recommended. The guidelines list several reasons for referral. Among them are:

* The occurrence of a life-threatening asthma episode.

* Personal or familial discontent with the current treatment.

* Unusual signs and symptoms which suggest a disease other than asthma.

* The presence of significant sinus disease, nasal polyps, allergic rhinitis, or acid reflux from the stomach.

* The necessity for additional tests such as skin testing or other diagnostic procedures.

* The patient or family needs more education and guidance.

* The patient is being considered for allergy injections (immunotherapy).

* An evaluation for occupational asthma is necessary.

In addition, the guidelines spell out the specific goals of therapy, underscoring the optimistic view that asthma can not only be controlled, but can be managed so that quality of life is uncompromised. Among these goals are:

* The prevention of chronic and/or troublesome symptoms.

* Maintaining normal activities, especially exercise.

* Preventing recurrent exacerbations of asthma and eliminating or minimizing the need for unscheduled physician visits, emergency room visits, or hospitalizations.

* Providing the most effective drugs with the fewest side effects.

* Meeting patients' (and families') expectations and achieving satisfaction with asthma care.

COMPONENT 2 Control of Factors Contributing to Asthma Severity

Since allergen elimination is an important goal in the management of most individuals with persistent asthma, all asthma patients should be questioned regarding their exposure to inhaled allergens, both indoors and out. In addition, many individuals with asthma should undergo allergy skin testing in order to evaluate the role of allergens in their disease and to recommend specific ways to avoid those allergens.

While allergen avoidance measures should be tailored to the patient's particular allergy profile and home environment, there are certain measures which are generally known to be helpful and are commonly recommended:

* If the patient is sensitive to an indoor pet, the pet should be removed from the home; if this is not possible, removal from the bedroom may be helpful.

* If the pet is allowed in the house, it should be kept away from upholstered furniture and carpets.

* For those who are sensitive to house dust mite allergens, it helps to encase mattress, box spring, and pillow in an allergy proof cover. Wash sheets and blankets weekly in very hot water (greater than 130 degrees F, if possible).

* Reduce indoor humidity to less than 50 percent. Avoid humidifiers, since dust mites and mold thrive on moisture.

* Remove carpets from the bedroom.

* In urban areas, where the cockroach allergen has become extremely prevalent, extermination should be strongly considered.

* For children with asthma, it's important to minimize the number of stuffed toys and animals in the bedroom.

* Indoor exposure to cigarette smoke and other forms of tobacco should be avoided at all cost.

Outdoor allergens are more difficult to avoid, but staying indoors in an air conditioned room and mold is high outdoors when the pollen can be very helpful.

In cases where it's impossible to simply avoid an allergen, immunotherapy--allergy injections--should be considered. Allergy injections are especially effective in individuals whose asthma has an allergic component. They appear to work better against pollen, house dust mites, and cat dander than against other allergens. Overall, immunotherapy should be considered for any asthma patients in whom there is clear evidence of a relationship between an allergen and the disease, difficulty in avoiding that allergen, and difficulty controlling symptoms with medications.

COMPONENT 3 Medications Used to Treat Asthma

There are two main types of medications that are used to treat asthma: those that provide rapid relief (short-acting beta agonists, anti-cholinergics, systemic steroids), and those that provide long-term control (inhaled anti-inflammatory agents, long-acting beta agonists, leukotriene modifiers).

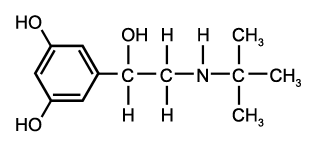

The medications most commonly called upon to provide quick relief of symptoms are the short-acting beta agonists, which work by stimulating receptors on smooth muscle cells in the bronchial tubes so that the muscles will relax and the tubes dilate, allowing air to pass through more easily. These are taken predominantly via an inhaler or nebulizer, though less potent oral forms are available. Their common names are albuterol (Proventil[R], Ventolin[R]), bitolterol (Tornalate[R]), pributerol (Maxair[R]), and terbutaline (Brethaire[R]). These medicines usually work within five minutes, but their effects last only four to six-hours. They can also be taken ten to fifteen minutes prior to exercising to prevent exercise-induced bronchospasm.

Another quick relief medication is ipratropium bromide (Atrovent[R]). This medication, taken via metered dose inhaler or nebulizer, is aimed at patients who have wheezing and coughing associated with chronic cigarette smoking.

Long-term control is provided by inhaled anti-inflammatory agents, which work to prevent and reduce airway inflammation, making the airways less sensitive to the triggers of asthma and perhaps even eliminating the inflammation completely. Because they don't work as intermittent therapy, they need to be taken every day.

The inhaled anti-inflammatory agents include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as cromolyn sodium (Intal[R]) and nedocromil sodium (Tilade[R]) and corticosteroids such as beclomethasone (Vanceril[R] and Beclovent[R]) flunisolide (AeroBid[R]), fluticasone (Flovent[R]), triamcinolone (Azmacort[R]), and budesonide (Pulmicort[R]). When taken at the recommended doses and with proper technique, the inhaled corticosteroids very rarely cause adverse effects.

Long-acting beta agonists work to dilate the bronchial tubes by relaxing the supporting smooth muscle. They work best when used in conjunction with anti-inflammatory agents. Among the long-acting beta agonists on the market today are salmeterol (Serevent[R]), albuterol (Volmax[R] and Proventil Repetabs[R]), and theophylline, which is sold under a variety of brand names. Salmeterol is an inhaled medication; the other two are taken orally.

The newest class of long-lasting controller medications is the antileukotrienes. These pharmaceuticals work by preventing the production--or blocking the effect--of chemical mediators known as leukotrienes, which appear to play an important role in inflaming the bronchial tubes of an asthma patient. The two anti-leukotriene agents presently available in the United States are zafirlukast (Accolate[R]) and zileuton (Zyflo[R]). These medications are available in tablet form to be taken two to four times per day.

When choosing among the variety of pharmaceuticals available, physicians are now educated by the guidelines to consider the severity of the disease: mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent or severe persistent. Patients with intermittent disease, for instance, benefit most from episodic bursts of a quick reliever like a beta agonist, with systemic steroids used for brief intervals during viral colds. Patients who have bothersome symptoms several times a week--mild intermittent disease--require the daily use of an anti-inflammatory controller medicine as well as occasional quick relief. A low-dose inhaled corticosteroid used twice a day along with a short-acting beta agonist inhaler used only for symptoms would be ideal. On the other hand, a patient who awakens at night, coughing and wheezing, and also has fairly frequent symptoms during the day, might need more than one controller. For this person, the prescription might include a long-acting beta agonist as well as a medium dosage inhaled corticosteroid. Finally, patients with extreme fluctuations in symptoms and peak flow might require the same medications, but with an increased dosage of inhaled corticosteroid, plus other controllers such as theophylline and/or the antileukotrienes, and possibly even an alternate day oral prednisone regimen.

These drug regimens are never set in stone: As the patient responds to the medication--or suffers disease exacerbations--the physician needs to decide whether to step up or step down the therapy, taking into consideration both benefit and risk.

COMPONENT 4 Education, Partnership, and Asthma Care

The final key to controlling asthma lies in the relationship between physician and patient. Patients need to know the basic facts about the pathophysiology of asthma, the role of medications, and environmental control measures; they need to develop the skills to self-medicate and to monitor their peak flow, if necessary. All of this should be discussed in great detail to create a partnership between physician and patient. In addition, a daily action plan should be established, complete with contingencies for changes in peak flow and/or increased symptoms. This will empower the patient in self-management, and provide a means toward an optimal quality of life. Only in this way can asthma become a manageable inconvenience rather than a potentially lethal nightmare.

COPYRIGHT 1998 Discover

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group