Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was the fifth leading cause of mortality in the United States in 1986, accounting for nearly 75,000 deaths and over 900,000 hospitalizations. [1] COPD affects an estimated 14 million Americans. Approximately 80 to 90 percent of deaths from COPD are attributable to cigarette smoking. [2] In future years, the prevalence of COPD is expected to increase among women, who tend to smoke more than men.

COPD is a general term for disorders characterized by airflow obstruction. [3] This definition excludes asthma (where airways obstruction is completely reversible) and specific causes of obstruction, such as bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis. In practical terms, COPD denotes a syndrome that encompasses varying degrees of chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Chronic bronchitis is characterized by the presence of cough and sputum production for at least three months per year for two consecutive years. [4] Emphysema is characterized pathologically by destruction of alveolar walls and clinically by the presence of hyperinflation, airflow obstruction and reduction in the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. [5]

Patients with COPD often have acute exacerbations superimposed on chronic disease. These episodes can occur in any season but are more common in the winter. Patients often complain of varying degrees of dyspnea, an increase in cough and sputum volume, and the production of purulent sputum. However, fever, leukocytosis and the appearance of new infiltrates on chest radiographs suggest pneumonia rather than an exacerbation of bronchitis.

Treatment of COPD is traditionally directed at improving air flow with bronchodilators, reducing airway inflammation with corticosteroids and treating infection with antibiotics. Although these strategies are widely accepted, clinical experience has not provided firm conclusions on their efficacy in patients with either stable disease or exacerbations. Uncertainty about the ideal treatment regimen is compounded by the common use of different types of drugs in combination.

Obviously, the first step in the treatment of individuals who smoke is to persuade them to stop smoking. Most clinicians then follow a hierarchy of treatment options, but the ideal regimen is still not known. (A comprehensive review of the literature can be found in an article by Ziment. [6])

A recommended approach to the treatment of exacerbations of COPD is summarized in Table 1.

First-Line Therapy

BETA-ADRENERGIC AGONISTS

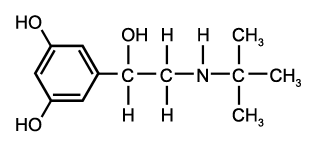

Sympathomimetic agents have long been among the mainstays of therapy for obstructive lung disease. In recent years, several agents have been introduced that have more selective activity on the [beta.sub.2] receptors, causing bronchodilation without

the troublesome side effects of [beta.sub.1]-agonist activity, such as tremor and tachycardia. These drugs include albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin), bitolterol (Tornalate), metaproterenol (Alupent, Metaprel), pirbuterol (Maxair) and terbutaline (Brethaire, Brethine, Bricanyl). Each of these agents can be administered by aerosol, which is preferable to oral administration because inhalation more rapidly delivers high concentrations of the agent to target receptors, with minimal systemic effect.

In most patients, a metered-dose inhaler, with or without a spacer attachment, is effective. In severe cases, a jet nebulizer can be used to deliver high doses of medication; however, repeated puffs of a metered-dose inhaler will have an equivalent effect. [6] Subcutaneous administration of epinephrine and terbutaline should be reserved for patients with very severe airways obstruction in whom aerosol administration is not possible.

Although many patients with COPD demonstrate no bronchodilator response on spirometry, some still benefit from treatment with beta agonists, particularly during acute exacerbations.

ANTICHOLINERGICS

Increased cholinergic activity of vagal fibers in the bronchi causes both smooth muscle contraction and increased bronchial gland secretion. Anticholinergics are effective bronchodilators in many patients with COPD, even in the absence of a demonstrable response to beta agonists on spirometry.

Anticholinergics are best administered by aerosol. Atropine, the prototypic agent, is a highly effective bronchodilator. However, atropine is well absorbed across the bronchial epithelial surface, which may provoke serious anticholinergic side effects, including tachycardia, ileus, urinary retention and mental status changes.

Ipratropium (Atrovent), a quaternary ammonium analog, is currently available only in a metered-dose inhaler. Ipratropium has minimal systemic absorption and virtually no anticholinergic side effects. The efficacy and safety of ipratropium have led many authors to recommend it as the initial form of therapy in both stable COPD and in exacerbations. The combination of ipratropium and a beta agonist has not been well studied, but the safety of each drug has encouraged use of this combination.

ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY

Exacerbations of chronic bronchitis are often assumed to be due to infection. Viral agents, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and other bacteria have been implicated as pathogens. Viruses may be isolated in 20 to 40 percent of patients with an exacerbation of COPD by may also be recovered in individuals with clinically stable disease. In patients with exacerbations, rhinovirus is the most common isolate. Influenza A is the most significant pathogen in terms of morbidity. [7] Therefore, influenza vaccine should be administered annually to patients with COPD. M. pneumoniae does not appear to be a common cause of exacerbations.

The role of bacteria in exacerbations of COPD is difficult to assess because pathogens frequently colonize the lower airways in patients with stable disease. The most common isolates are haemophilus influenza, streptococus pneumoniae and Morazella catarrhalis. [7] M. catarrhalis was once though to be a commensal of the upper respiratory tract but has recently been recognized as an important cause of lower respiratory tract infections, including pneumonia. [8,9]

Patients with exacerbations of COPD are usually treated with antibiotics, although this practice has not been supported by definitive clinical trials. In one study of antibiotic therapy for exacerbations of COPD, [10] 173 patients with COPD were followed for a mean of 24 months. During this time, 448 exacerbations occured; in 182 episodes, trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin or doxycycline was used, and in 180 episodes, placebo was used.

Patients who received antibiotics had more rapid improvement in peak flow rates. Furthermore, the probability of clinical deterioration (defined as worsening of symptoms necessitating hospitalization or unblinded antibiotic treatment) was 10 percent in patients treated with antibiotics, compared with 19 percent in patients who received placebo. Clear improvement occured in 68 percent of antibiotic-treated exacerbations, compared with 55 percent of the exacerbations in the placebo group.

The advantage of antibiotic therapy was most pronounced in patients with exacerbations characterized by increased dyspnea, increased sputum volume and purulent sputum. In individuals with only one of these symptoms, there was no clear difference between those receiving antibiotics and those receiving placebo. it therefore seems reasonable to administer at least a seven-day course of antibiotics during exacerbations of COPD, particularly in patients who appear ill and certainly in those with increased dyspnea, increased sputum volume and purulent sputum.

Establishing a specific bacateriologic diagnosis during a COPD exacerbation is difficult because it is uncertain whether isolates are merely colonizing the lung or are truly pathogenic. Because blood cultures i this setting are rarely positive, treatment is usually empiric. The choice of antibiotic should be directed against the likely pathogens, H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae and M. catarrhalis.

The antibiotics commonly used in the treatment of exacerbations of COPD are listed in Table 2. Resistance to some of these agents has been observed. H. influenzae, the most common isolate, is often resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin, cephalexin (Keflex) and erythromycin. S. pneumoniae may be resistant to tetracycline, and the activity of ciprofloxacin (Cipro) against this organism has been questioned. M. catarrhalis usually produces beta lactamases and may be relatively resistant to ampicillin and amoxicillin.

Second-Line Therapy

CORTICOSTEROIDS

The value of glucocorticoids in the treatment of asthma is well recognized. In theory, the anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoids and their ability to potentiate the effects of bronchodilators should make them useful agents in the management of patients with COPD, paticularly those with chronic bronchitis. However, the role of glucocorticoids in the treatment of stable COPD is controversial, and there is little evidence to support use of glucocorticoids during acute exacerbations. [6] Nevertheless, many clinicians administer high doses of steroids to patients with COPD who continue to deteriorate despite otherwise vigorous medical management. If steroids are used, the dosage should be tapered as soon as symptons improve. Aerosolized steroid appear to be of no value in patients with COPD.

THEOPHYLLINE

Theophylline has long been used to treat reversible airflow obstruction, including exacerbations of COPD. Theophylline has bronchodilator activity but is probably less effective than the beta agonists and has greater potential for toxicity and adverse interactions with other drugs. In study of 28 patients hospitalized because of exacerbations of COPD, [11] 14 patients received intravenous aminophylline and 14 received placebo. (All of the patients received aerosolized metaproterenol, methylprednisolone, antibiotics and oxygen.) No differences were seen between the two groups with regard to improvement in air flow, dyspnea or arterial blood gas measurements. However, six of the patients treated with aminophylline developed tremor, palpitations or nausea, compared with only one patient in the control group.

Theophylline appears to have beneficial effect in a subgroup of patients with severe, stable disease, perhaps because of its ability to augment inspiratory muscle contractility. [12] Therefore, a therapeutic trial of theophylline in patients with stable but severe COPD is reasonable, but the drug should be stopped if no clear improvement in symptoms is noted on spirometry.

[TABULAR DATA OMITTED]

Final Comment

Treatment of exacerbations of COPD focuses on improving air flow and eradicating infection. Aerosolized beta agonists and ipratropium, either alone or in combination, represent relatively effective and safe initial management. Corticosteroids and theophylline are generally reserved for more severe exacerbations that do not respond to first-line agents, because their efficacy in this setting seems questionable.

Patients with increased dyspnea, increased sputum volume and purulent sputum should receive antibiotics. Because of the inherent uncertainty about a bacteriologic diagnosis on the basis of cultures of expectorated sputum, the choice of antibiotic is empiric. The ideal agent should be active against the common bacterial pathogens and have a low incidence of adverse reactions.

REFERENCES

[1] Higgins MW. Chronic airways disease in the United State. Trends and determinants. Chest 1989;96 (3 Suppl):328S-34S.

[2] Chronic obstructive lung disease: summary of the health consequences of smoking. A report of the Surgeon General. Bethesda, Md.: Department of Health and Human Service, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1984.

[3] American Thoratic Society. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;136:225-44.

[4] Terminolgy, definition and classifications of chronic pulmonary emphysema and related conditions. Thorax 1959;14:286-99.

[5] Snider GL, Kleinerman J, Thurlbeck WB, Bengali ZH. The definition of emphysema. Report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Division of Lung Disease workshop. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;132:182-5.

[6] Ziment I. Pharmacologic therapy of obstructive airway disease. Clin Chest Med 1990;11: 461-86.

[7] Nicotra MB, Rivera M. Chronic bronchitis: when and how to treat. Semin Respir Infect 1988;3:61-71.

[8] Nicotra B, Rivera M, Luman JI, Wallace RJ Jr. Branhamella catarrhalis as a lower respiratory tract pathogen in patients with chronic lung disease. Arch Intern Med 1986;146:890-3.

[9] Wright PW, Wallace RJ Jr., Shepherd JR. A descriptive study of 42 cases of Branhamella catarrhalis pneumonia. Am J Med 1990; 88(5A):2S-8S.

[10] Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GK, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1987;106:196-204.

[11] Rice KL, Leatherman JW, Duane PG, et al. Aminophylline for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1987;107:305-9.

[12] Murciano D, Auclair MH, Pariente R, Aubier M. A randomized, controlled trial of theophylline in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1521-5.

MARK J. ROSEN, M.D. is chief of Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine at Beth Israel Medical Center, New York City. A graduate of Brown University School of Medicine, Providence, R. I., Dr. Rosen completed an internship and a residency in medicine at Mt. Sinai Hospital, a fellowship in pulmonary diseases at Mt. Sinai Medical Center and one in critical care medicine at St. Vincent's Medical Center, all in New York City.

COPYRIGHT 1992 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group