The need for intense therapy in the management of asthma is closely linked to the assessment of severity of disease exhibited by the patient. In recent guidelines by an expert panel[1] for the diagnosis and management of asthma, asthma severity is stratified into mild, moderate, and severe. Clinical characteristics of severe asthma include continuous symptoms, limited activity level, frequent exacerbations, frequent nocturnal symptoms, and occasional hospitalization/emergency treatment. Assessment of severity by lung function includes an [FEV.sub.1] of less than 60% of baseline and more than 20% to 50% peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) variability. The goals of intense pharmacotherapy would include the following: improved pulmonary function, reduced peak flow variability, almost normal activity, infrequent awakening at night, reduced frequency of exacerbations, reduced frequency of as needed inhaled bronchodilators, reduced need for oral corticosteroid, burst therapy, and reduced need for emergency department treatment. Dr. A. Woolcock[2] have divided asthma severity into mild, moderate, severe, and life threatening (Table 1). Clinical characteristics range from the use of bronchodilator therapy intermittently to loss of consciousness and the need for ventilatory assistance. With increase in severity, there is a fall in peak expiratory flow rate and increased variability of peak expiratory flow measurements. In addition, there is a progressive increase in bronchial hyperresponsiveness (BHR) with increasing severity of asthma. This phenomenon has been shown by many groups using histamine or methacholine.[3] The BHR is related to intense inflammation of the airways.[4,5] The clinician can assess increased BHR by increases of cough and wheeze with a deep breath, exercise and in response to environmental stimuli (eg, cold air) that would not bother normal individuals. In addition, severity can be judged by changes in flow rate, blood gas analysis, and by the clinical findings of paradoxical pulse, strong accessory muscle contractions, decreased breath sounds, and evidence of disturbed consciousness.[3]

The clinician treating severe asthma has a variety of pharmacologic agents that can be intensified in the treatment of these individuals. These include inhaled [beta]-agonists, antiinflammatory agents, inhaled corticosteroids and cromolyn, oral sustained release theophylline, and oral corticosteroids.

BRONCHODILATORS

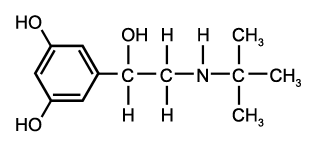

There is a variety of commercially available inhaled [beta.sub.2]-agonists (Table 2).[3] Albuterol is characteristics of the newer class of selective [beta.sub.2]-agents extensively used in the management of asthma. This agent is available for nebulization, as a metered dose inhaler (MDI), as an oral preparation, as well as a powder for inhalation. Only terbutaline is available for subcutaneous injection. It is usually assumed that patients with severe asthma are already using an inhaled [beta]-agonist, but with an exacerbation of asthma at home, they should be questioned about the use of these inhalers. These patients may have had a lapse in medication refill and may have been without bronchodilator therapy. Current guidelines[1] indicate that an additional 2 puffs of a [beta]-agonist can be taken every 20 min for up to 1 h if needed. If there is an incomplete or poor response to this therapy, the patient should seek medical attention at the nearest emergency room.

For the treatment of an acute exacerbation in the physician's [TABULAR DATA OMITTED] office, epinephrine, 1:1,000 wt/vol solution, is still the

Table 2--Commercially Available [beta.sub.2]-Bronchodilators

standard of therapy. Three-tenths of a milliliter of a 1:1000 wt/vol solution is adequate for most adults and can be repeated at 15-min intervals up to 3 doses. If the patient has not had significant relief after the second dose and still exhibits signs of severe asthma, serious consideration is given to sending the patient to the emergency room.

INHALED CORTICOSTEROIDS

A major addition for treatment of severe asthma has been the use of inhaled corticosteroids (Table 3).[6,7] Budisonide is not yet available in the United States but is used extensively in Europe. Although it has a theoretic advantage with a higher ratio of topical to systemic potency, controlled trials have not shown it to be superior to beclomethasone.[6] A commonly used inhaled steroids, beclomethasone dipropionate has been shown to be successful in treating chronic severe asthma as illustrated in a study by Salmeron et al.[8] These investigators took a group of 43 steroid-dependent asthmatics, and prior to the study, cleared their symptoms with prednisolone, 0.5 mg/kg/day for 14 days. These patients had typical severe intrinsic asthma with mean duration of asthma symptoms from 13 to 15 years and approximately 3 exacerbations of asthma a week. These patients were maintained on a standard regimen of inhaled salbutamol (2 puffs, 4 times a day) and long acting theophylline, 10 mg/kg/day given bid. They were then randomized to placebo or beclomethasone groups (1,500 [mu]g/day). One half of the placebo-treated patients had a severe exacerbation of asthma which required oral corticosteroid treatment in the first 28 days as compared to only 1 individual in the beclomethasone-treated group. The individuals treated with beclomethasone were able to maintain normal morning and evening peak expiratory flow measurements in comparison with a 50% reduction in peak flow in the placebo-treated individuals (Fig 1). This study is illustrative of the many fine studies showing the effectiveness of high-dose inhaled steroids in severe asthma.[6] Beclomethasone inhalers containing 250 [mu]g per puff are not yet available in the United States.

Table 3--Inhaled Topical Steroids for Asthma

Triamcinolone has been extensively studied in doses of 400 to 2,000 [mu]g per day. Falliers et al[9] studied inhalation doses of 400 to 1,400 [mu]g per day in severe steroid-dependent adult asthmatics. There was a return to normal adrenal function in those patients able to discontinue oral steroids with minimal side effects of sore throat and hoarseness, and a low incidence of oral thrush. Flunisolide, 250 [mu]g 4 times daily, was compared with beclomethasone, 100 [mu]g 4 times daily, with no significant differences in outcome in 30 steroid-dependent asthmatics.[10]

SYSTEMIC CORTICOSTEROIDS

The corticosteroids available for control of severe asthma are shown in Table 4. Prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone are commonly used to suppress severe exacerbations of asthma and are preferred because of their relatively short serum half-life. Prednisone is the corticosteroid of choice at Northwestern. It has been found to be highly effective in controlling severe asthma and is relatively inexpensive. Forty to sixty milligrams of prednisone is given for 5 to 7 days to control flare-ups of severe asthma which may follow environmental allergen exposure, viral respiratory infection, or in steroid-dependent asthmatics whose symptoms are not being controlled by using inhaled topical corticosteroids. These medications can be stopped after 5 to 7 days, or continued in an alternate day dosage with gradual tapering at 5 mg every 2 weeks with assessment for asthma control at every reduction.

There is a subgroup of severe corticosteroid-dependent asthmatics who require split dose daily therapy at 40 to 50 mg bid to control symptoms. In addition, some of these patients fail alternate day therapy and can be successfully managed with bid prednisone given on alternate days. The evening prednisone dose is the first to be tapered.

Tapering of high-dose oral corticosteroids is always done with the aid of inhaled topical steroids used in maximum doses. With the advent of these potent inhaled topical steroids, it is the rare steroid-dependent asthmatic whose symptoms cannot be managed with alternate day prednisone therapy.

To control a severe asthmatic attack in the hospital or in an emergency room situation, corticosteroids have a marked beneficial role. In this situation, inhaled corticosteroids are [TABULAR DATA OMITTED]

of little value and may increase symptoms because of marked bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Corticosteroids are given intravenously in the range of 200 mg of hydrocortisone every 4 to 6 h or equivalent dose of methylprednisolone (40 mg every 4 to 6 h. There have been studies[13] of high dose intravenously administered steroids in the treatment of severe asthma. None of these has shown any advantage over moderate intravenously administered hydrocortisone (or methylprednisolone equivalent) in the range of 200 to 400 mg every 4 to 6 h.

OTHER AGENTS

Cromolyn sodium is an antiinflammatory compound with minimal side effects. It has a role in the treatment of moderately severe asthma, especially in children with allergic triggers of asthma. In the moderately severe asthmatic child cromolyn can be used at 2 puffs qid. Cromolyn may have to supplemented with inhaled topical corticosteroids in the more severe case of childhood asthma.[14]

There has been a shift away from theophylline compounds in the treatment of severe asthma in recent years. This is because of its moderate therapeutic effect and its narrow window of therapeutic eficacy. Long-acting theophylline preparations can be given at night in those steroid-dependent asthmatics who show an exacerbation of symptoms in the early morning.[13]

There are several drugs under investigation, such as gold salts and methotrexate, that are being explored for the treatment of steroid-dependent asthmatics that can not achieve low-dose daily or alternate day steroid therapy.[4] These drugs are clearly still experimental.

(*1)From the VA Lakeside Medical Center, Chicago.

(*2)Adapted from Woolcock.[2] PEF, peak expiratory flow; BD(A), bronchodilator aerosol; [PD.sub.20], provoking dose required for 20% fall in [FEV.sub.1]; [PC.sub.20], provoking concentration required for 20% fall in [FEV.sub.1].

(*3)Adapted from George and Owens.[3]

[unkeyable]M = metered dose inhaler; N = solution of nebulization; O = oral preparation; P, inhaled powder; and S, subcutaneous injection.

(*4)Adapted from Townley and Suliamon[11] and Lieberman and Erffmeyer.[12] Suitable for alternate-day therapy.

REFERENCES

1 National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute--National Asthma Education Program--Expert Panel Report. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol 1991; 5:57-188

2 Woolcock AJ. Use of corticosteroids in treatment of patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1989; 84:975-78

3 George RB, Owens MW. Bronchial asthma. Dis Month 1991; 37:137-96

4 Barnes P. New approach to the treatment of asthma. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1517-27

[5] Barnes PJ. Effect of corticosteroids on airway hyperresponsiveness. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 141:570-76

[6] Konig P. Inhaled corticosteroids: their present and future role in the management of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1988; 88:297-306

[7] Smith MJ. The place of high dose inhaled corticosteroids in asthma therapy. Drugs 1987; 33:423-29

[8] Salmeron S, Guerin JC, Godard P, et al. High doses of inhaled corticosteroids in unstable chronic asthma: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989; 140:167-71

[9] Falliers CJ. Triamcinolone acetonide aerosols for asthma: I, effective replacement of systemic corticosteroids therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1976; 57:1-6

[10] Spector S. The use of corticosteroids in the treatment of asthma. Chest 1985; 87:73-79

[11] Townley RG, Suliamon F. The mechanism of corticosteroids in treating asthma. Ann Allergy 1987; 58:1-6

[12] Lieberman P, Erffmeyer JE. Corticosteroids in the treatment of allergic diseases. In: Patterson R, ed. Allergic diseases; diagnosis and management. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co, 1985; 759-92

[13] Britton MG, Collins JV, Brown D, et al. High dose corticosteroids in severe acute asthma. BMJ 1976; 2:73-74

[14] Cockcraft DW, Hargreave FE. Outpatient management of bronchial asthma. Med Clin North Am 1990; 74:797-809

COPYRIGHT 1992 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group