Peripartum emergencies occur in patients with no known risk factors. When the well-being of the fetus is in question, the fetal heart rate pattern may offer etiologic clues. Repetitive late decelerations may signify uteroplacental insufficiency, and a sinusoidal pattern may indicate severe fetal distress. Repetitive variable decelerations suggesting umbilical cord compression may be relieved by amnioinfusion. Regardless of the atiology of the nonreassuring fetal heart pattern, measures to improve fetal oxygenation should be attempted while options for delivery are considered. Massive obstetric hemorrhage requires prompt action. Clinical signs, such as painless bleeding, uterine tenderness and nonreassuring fetal heart patterns, may help to differentiate causes of vaginal bleeding that may or may not require emergency cesarean delivery. The causes of postpartum hemorrhage include uterine atony, vaginal or cervical laceration, and retained placenta. The challenge of managing shoulder dystocia is to effect a rapid delivery while avoiding neonatal and maternal morbidity. The McRoberts maneuver has been shown to be the safest and most successful technique for relieving shoulder dystocia. Eclampsia responds best to magnesium sulfate, supportive care and supplemental hydralazine or labetalol as needed for severe hypertension.

Family physicians who provide maternity care must be prepared to manage peripartum emergencies. Obstetric complications may occur in patients without previous risk factors. This article reviews four types of common emergencies during labor and delivery: nonreassuring fetal status, maternal hemorrhage, fetal shoulder dystocia and eclampsia.

Nonreassuring Fetal Status

With the introduction of electronic fetal monitoring, use of the diagnosis "fetal distress" increased from 0.6 percent of all U.S. pregnancies in 1974 to 5.8 percent of pregnancies in 1984.[1] According to current thinking, fetal distress has been overdiagnosed. In industrialized nations, overuse of this diagnosis has resulted in soaring cesarean delivery rates without any appreciable decrease in the incidence of Cerebral palsy.[2] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) now recommends that instead of the term "fetal distress" the term "nonreassuring fetal status" be used to refer to suspicious fetal heart tracings, since most nonreassuring tracings end with the birth of normal, healthy infants.[3]

When fetal well-being is in question, the fetal heart tracing may offer clues to the etiology of the problem. Repetitive late decelerations of the fetal heart rate may signal uteroplacental insufficiency. Deep, prolonged decelerations or sudden bradycardia during the second stage of labor suggest cord compression, for which expeditious delivery often results in a good perinatal outcome.[4] Sinusoidal tracings are frequently associated with critically distressed fetuses. Nonreactive tracings are not in themselves ominous, provided that short-term variability is normal.[5]

Repetitive variable decelerations suggest umbilical cord compression, especially in the presence of oligohydramnios or amniotomy.[6] In this situation, transcervical amnioinfusion reduces decelerations and the rate of cesarean sections by nearly one half. A 250- to 500-mL bolus of normal saline at room temperature may be infused through a standard intrauterine pressure catheter. The bolus infusion is then followed by a maintenance infusion of 3 mL per minute. It is extremely important to verify that fluid is flowing from the vagina and that volume overload is not occurring. Amnioinfusion should not be performed if there are late decelerations, a fetal scalp pH of less than 7.2, abruptio placentae, placenta previa, previous vertical uterine incision or known uterine anomalies.

When the fetal heart tracing is nonreassuring, ACOG[7] recommends that the physician consider obtaining a confirmatory scalp pH sample while attempting to correct the underlying problem. Alternatives to scalp sampling include fetal acoustic stimulation[8] and fetal scalp stimulation.[9] In prospective trials,[8,9] these techniques have been found to correlate reliably with a fetal scalp pH of 7.2 or greater if they produce a reassuring heart rate acceleration. In the event of bradycardia or a sudden, deep deceleration, the cervix should be examined immediately to rule out umbilical cord prolapse. If the cord has prolapsed, the physician should elevate the presenting part with the examining fingers while preparing for immediate cesarean delivery: This strategy may be effective even with an occult cord prolapse.[10]

Another etiology to consider is uterine rupture, which may cause fetal distress before vaginal bleeding and pain begin. Prolonged fetal heart rate decelerations have also been reported after the administration of epidural anesthesia, even when maternal blood pressure is normal.[11]

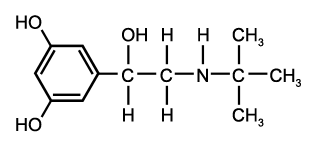

Regardless of the etiology of the nonreassuring fetal tracing, general measures to improve fetal oxygenation may help while the fetal tracing is monitored (Figure 1). Fetal oxygen content and saturation can be improved by placing the mother in the lateral recumbent position and administering oxygen at 8 to 10 L per minute.[12] Oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon) should be discontinued. Tocolysis should be considered, as should intravenous hydration if the volume status is in question. Beta-mimetics such as terbutaline (Bricanyl), 0.25 mg administered subcutaneously, have been found to be superior to placebo and to magnesium sulfate in relieving decelerations.[13]

[Figure 1 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

When conservative measures fail, the family physician must decide whether a nonreassuring tracing mandates operative delivery and, if so, how urgently. The physician should not hesitate to seek obstetric consultation early in the course of potential fetal compromise, especially when intrauterine resuscitation fails. Both physicians must carefully document the details of the labor, providing meticulous evidence for each clinical decision.

Obstetric Hemorrhage

Although much less common than in the past, obstetric hemorrhage is still responsible for 13.4 percent of all maternal deaths in the United States.[14] As with any emergency, the assessment of obstetric hemorrhage begins with the ABCs (airway, breathing and circulation).

Patients with hemodynamic instability or massive hemorrhage require prompt resuscitative measures, including the administration of supplemental oxygen, the placement of two intravenous lines, intravenous hydration, and blood typing and crossmatching for the replacement of packed red blood cells. If a transfusion must be given before full crossmatching is finished, type-specific uncross-matched blood can be used.[15]

Antepartum Hemorrhage

When a patient in labor presents with vaginal bleeding, the physician must consider several possible causes (Figure 2). Placenta previa should be ruled out when a patient has copious vaginal bleeding. The classic presentation of placenta previa is painless vaginal bleeding and a soft, nontender uterus. If readily available, ultrasonography should be performed immediately, since placenta previa can be quickly and accurately diagnosed by ultrasound examination.[16] When ultrasonography is not available, gentle speculum examination may be considered, as long as the bleeding is not brisk. This examination should be performed with a "double set-up" in case immediate cesarean section is required.

[Figure 2 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

The patient who complains of abdominal pain between uterine contractions or a tender uterus must be presumed to have abruptio placentae. Since ultrasound examination has a high false-negative rate in diagnosing abruption,[17] this obstetric complication is diagnosed clinically. In one prospective study,[18] 78 percent of patients with abruptio placentae presented with vaginal bleeding, 66 percent with uterine or back pain, 60 percent with fetal distress and only 17 percent with uterine contractions or hypertonus. The management of abruptio placentae is primarily supportive and entails both aggressive hydration and monitoring of maternal and fetal well-being.[19] Coagulation studies should be performed, and fibrinogen and D dimers or fibrin degradation products should be measured to screen for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Packed red blood cells should be typed and held. If the fetus appears viable but compromised, urgent cesarean delivery should be considered.

The presentation of uterine rupture may be similar to that of abruptio placentae. Signs and symptoms include vaginal bleeding, uterine pain and a nonreassuring fetal tracing. Uterine rupture occurs in 0.2 to 0.8 percent of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) deliveries.[20] In general, however, a trial of labor after previous low transverse uterine incision is safe and usually successful.[21] Uterine rupture also occurs more commonly in cocaine abusers or patients who have been given high doses of oxytocin or prostaglandins. On palpation, the uterine fundus may feel boggy and tender, and it may seem to be expanding. Intrauterine pressure monitoring has not proved helpful in diagnosing uterine rupture.[22] Treatment includes aggressive resuscitation and urgent surgical delivery.

A history of abrupt onset of vaginal bleeding that began with rupture of membranes suggests vasa previa, especially when bleeding is accompanied by decreased fetal movement and a nonreassuring fetal tracing. Urgent cesarean section is generally performed. The differential diagnosis of antepartum vaginal bleeding also includes normal "bloody show" and mucopurulent cervicitis. Vasa previa should be suspected when bloody show is excessive.

Postpartum Hemorrhage

If the placenta has not delivered when hemorrhage begins, it should be removed, by manual exploration of the uterine cavity if necessary (Figure 3). Placenta accreta is diagnosed if the placental cleavage plane is indistinct. In this situation, the patient should be prepared for probable urgent hysterectomy. Firm bimanual compression of the uterus (with one hand in the posterior vaginal fornix and the other on the abdomen) can limit hemorrhage until help can be obtained.

[Figure 3 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Hemorrhage after placental delivery should prompt vigorous fundal massage while the patient is rapidly given 10 to 30 units of oxytocin in 1 L of intravenous fluid. If the fundus does not become firm, uterine atony is the presumed (and most common) diagnosis. While fundal massage continues, the patient may be given 0.2 mg of methylergonovine (Methergine) intramuscularly, with the dose repeated at two- to four-hour intervals if necessary. Methylergonovine may cause cramping, headache and dizziness. The use of this drug is contraindicated in patients with hypertension. Carboprost (Hemabate), 15-methyl prostaglandin [F.sub.2a], may be administered intramuscularly or intramyometrially in a dosage of 250 [micro]g every 15 to 90 minutes, up to a maximum dosage of 2 mg. As many as 68 percent of patients respond to a single carboprost injection, with 86 percent responding by the second dose.[23] Since oxygen desaturation has been reported with the use of carboprost,[24] patients should be monitored by pulse oximetry.

Continuing hemorrhage in a patient with a firm uterine fundus may indicate a hidden vaginal or cervical laceration. This type of injury is easier to identify and repair with adequate lighting, exposure and assistance. If no laceration is present and the fundus is firm, the uterus requires gentle but thorough manual exploration for retained placenta, which should be removed. Uterine rupture is occasionally evident and requires immediate surgery.

An occult uterine inversion may also be discovered on vaginal examination, or it may present frankly. Uterine inversion is somewhat more common in primiparas and has no clear association with the mismanagement of labor.[25] Because uterine inversion quickly leads to shock, the physician should order brisk intravenous hydration and grasp the uterus in the palm, with the thumb anterior. The uterus is then firmly pushed backup into the abdominal cavity and held in place for several minutes. Magnesium sulfate, 4 g given intravenously, and terbutaline, 0.25 mg given intravenously, have been reported to aid repositioning.[26]

If uterine exploration is nondiagnostic and the fundus is firm, rarer causes of hemorrhage should be considered. While puerperal hematomas typically cause a vulvar or vaginal mass, an occult retroperitoneal hematoma can present with severe abdominal pain and shock after delivery. The diagnosis is confirmed on laparotomy. Visible hematomas that are less than 4 cm in size and not expanding may be managed with ice packs and observation. Larger or expanding hematomas must be incised, irrigated and packed, with ligation of any obvious bleeding vessels. If venipuncture sites are oozing, coagulopathy should be considered.

Shoulder Dystocia

Shoulder dystocia, a dreaded and unpredictable obstetric complication, reportedly occurs in 0.23 to 1.60 percent of deliveries.[27,28] In one recent retrospective analysis,[29] the only independent risk factors for shoulder dystocia were a fetal weight greater than 4 kg (8 lb, 13 oz) and a previous macrosomic infant. Macrosomia is notoriously difficult to predict before delivery. Evidence for other predictive risk factors, such as maternal obesity, maternal diabetes or labor abnormalities, is unclear.[28,30] An important exception is assisted vaginal delivery. In a recent large retrospective study,[31] it was found that assisted delivery often leads to shoulder dystocia when the fetus is macrosomic or the mother is diabetic.

Since shoulder dystocia is difficult to predict or prevent, the physician must know how to manage it. The condition is not difficult to diagnose. Typically, the fetal head delivers and then retracts onto the maternal perineum in the so-called "turtle sign." The anterior fetal shoulder then fails to deliver, even with moderate posterior traction on the head. The challenge is to effect delivery as quickly as possible while attempting to avoid the neonatal morbidity that complicates more than one third of shoulder dystocias.[27]

The recommended sequence for reducing shoulder dystocia begins with calling for help and asking the mother to stop her pushing efforts (Figure 4). The first step is the McRoberts maneuver, in which assistants hyperflex the mother's hips against her abdomen, thereby rotating the symphysis pubis anteriorly and decreasing the forces needed to deliver the fetal shoulders (Figure 5). A recent retrospective study[32] found this maneuver to be the safest and most successful technique for relieving shoulder dystocia. An assistant can add gentle posterolateral suprapubic pressure while the physician continues moderate posterior traction on the fetal head (Figure 6). Fundal pressure should be avoided, since it tends to increase the impaction.

[Figures 4-6 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

If the McRoberts maneuver does not result in delivery, the physician may want to perform an episiotomy (if needed) and call in the anesthesia and neonatal teams. The Rubin maneuver (or the reverse Woods screw) can then be tried. In this maneuver, the physician presses firmly on the posterior aspect of the infant's posterior shoulder, narrowing and rotating the shoulder girdle into the oblique angle at which delivery is often possible (Figure 7).

[Figure 7 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

The next alternative is to deliver the posterior arm. The physician slides a hand under the posterior shoulder to the infant's elbow. By applying pressure at the antecubital fossa, the physician flexes the fetal arm, which is grasped and pulled out over the chest to deliver the shoulders.

In the unusual event that none of these maneuvers is successful, the controversial Zavanelli maneuver may be attempted. In this procedure, the fetal head is rotated to a direct occipitoanterior position, flexed, replaced in the vagina and held there until a cesarean section is performed.

The key principle with all of these maneuvers is that the physician should formulate and rehearse a consistent management plan. In this way, the physician and other attendants will be prepared to handle shoulder dystocia effectively.

Eclampsia

In developed countries, eclampsia has been reported to occur in 0.05 to 0.32 percent of pregnancies. Although several recent reports[33] indicate that the mortality rate for eclampsia is now less than 2 percent, serious complications still occur in up to 35 percent of affected women. Perinatal mortality rates range from 2.0 to 8.6 percent.[34] The clinical course of eclampsia is usually gradual; however, in one recent U.S. series,[35] 20 percent of patients either did not have the classic preeclamptic triad (elevated blood pressure, proteinuria and edema) or had only mild signs.

In the United States, magnesium sulfate has long been the drug of choice for controlling eclamptic seizures. In the United Kingdom, a large randomized trial[36] and a recent metaanalysis[37] both found that magnesium sulfate was associated with 60 to 70 percent fewer recurrent seizures than were diazepam and phenytoin. Fewer intubations were necessary in the neonates of eclamptic women who were treated with magnesium sulfate. In addition, fewer of these newborns had to be placed in neonatal intensive care units.

In the treatment of eclampsia and preeclampsia, magnesium sulfate is often given according to Zuspan's regimen[38]: an initial 4-g intravenous bolus, then 1 to 2 g per hour as a continuous infusion. If serum magnesium levels exceed 10 mEq per L (5 mmol per L), respiratory depression may occur. This problem may be counteracted by the rapid intravenous infusion of l0 mL of 10 percent calcium gluconate. Magnesium sulfate should be used with caution in patients with impaired renal or cardiac status. It should not be used in patients with myasthenia gravis.

Since magnesium sulfate has no effect on blood pressure, antihypertensive agents are often initiated if the diastolic blood pressure exceeds 105 to 110 mm Hg. The purpose is to decrease the risk of maternal intracranial hemorrhage without unduly jeopardizing uterine blood flow. For this purpose, a recent randomized controlled trial[39] found that when administered as a bolus, hydralazine and labetalol were about equally safe and effective. Hydralazine is given intravenously in a dosage of 5 to 10 mg every 20 minutes. Labetalol is given in an intravenous dose of 50 to 100 mg every 20 to 30 minutes, up to a total dosage of 300 mg.[38]

Additional management of eclampsia includes supportive care with gentle intravenous hydration and continuous fetal monitoring. Delivery should be accomplished as soon as the mother is stable, by the vaginal route if possible. Obstetric consultation should be sought as early as possible in the course of the eclamptic episode.

The author thanks Joseph Scherger, M.D., M.P.H., for editorial contributions to the manuscript.

REFERENCES

[1.] Shiono PH, McNellis D, Rhoads GG. Reasons for the rising cesarean delivery rates: 1978-1984. Obstet Gynecol 1987;69:696-700.

[2.] Stanley FJ, Watson L. Trends in perinatal mortality and cerebral palsy in Western Australia, 1967 to 1985. BMJ 1992;304:1658-63.

[3.] Committee on Obstetric Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Fetal distress and birth asphyxia: ACOG committee opinion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1994;45:302.

[4.] Herbert CM, Boehm FH. Prolonged end-stage fetal heart rate deceleration: a reanalysis. Obstet Gynecol 1981;57:589-93.

[5.] Odendaal H J, Steyn W, Theron GB, Norman K, Kirsten GF. Does a nonreactive fetal heart rate pattern really mean fetal distress? Am J Perinatol 1994; 11:194-8.

[6.] Hofmeyr GJ. Amnioinfusion for intrapartum umbilical cord compression. In: Neilson JP, Crowther CA, Hodnett ED, Hofmeyr G J, eds. Pregnancy and childbirth module of the Cochrane Library [database on disk and: CD-ROM], The Cochrane Collaboration. Issue 1. Oxford: Update SOftwear, 1998. Updated quarterly.

[7.] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Fetal heart rate patterns: monitoring, interpretation, and management. Technical bulletin 207-July 1995. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1995;51:65-74.

[8.] Smith CV, Nguyen HN, Phelan JR Paul RH. Intrapartum assessment of fetal well-being: a comparison of fetal acoustic stimulation with acid-base determinations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986;155: 726-8.

[9.] Clark SL, Gimovsky ML, Miller FC. The scalp stimulation test: a clinical alternative to fetal scalp blood sampling. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984;148:274-7.

[10.] Cohen WR, Schifrin BS, Doctor G. Elevation of the fetal presenting part: a method of intrauterine resuscitation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1975; 123:646-9.

[11.] Steiger RM, Nageotte MP. Effect of uterine contractility and maternal hypotension on prolonged decelerations after bupivacaine epidural anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:808-12.

[12.] Carbonne B, Benachi A, Leveque ML, Cabrol D, Papiernik E. Maternal position during labor: effects on fetal oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88:797-800.

[13.] Hofmeyr GJ. Betamimetics for suspected intrapartum fetal distress. In: Neilson JP, Crowther CA, Hodnett ED, Hofmeyr G J, eds. Pregnancy and childbirth module of the Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD-ROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software, 1998. Updated quarterly.

[14.] Kaunitz AM, Hughes JM, Grimes DA, Smith JC, Rochat RW, Kafrissen ME. Causes of maternal mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 1985;65:605-12.

[15.] Gervin AS, Fischer RP. Resuscitation of trauma patients with type-specific uncrossmatched blood. J Trauma 1984;24:327-31.

[16.] Bowie JD, Rochester D, Cadkin AV, Cooke WT, Kunzmann A. Accuracy of placental localization by ultrasound. Radiology 1978; 128:177-80.

[17.] Jaffe MH, Schoen WC, Silver TM, Bowerman RA, Stuck KJ. Sonography of abruptio placentae. A JR Am J Roentgenol 1981;137:1049-54.

[18.] Hurd WW, Miodovnik M, Hertzberg V, Lavin JP. Selective management of abruptio placentae: a prospective study. Obstet Gynecol 1983;61:467-73.

[19.] Turner LM. Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1994;12:45-54.

[20.] Martins ME. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Clin Perinatol 1996;23:141-53.

[21.] Phelan JP, Clark SL, Diaz F, Paul RH. Vaginal birth after cesarean. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;157: 1510-5.

[22.] Rodriguez MH, Masaki DI, Phelan JP, Diaz FG. Uterine rupture: are intrauterine pressure catheters useful in the diagnosis? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989; 161:666-9.

[23.] Hayashi RH, Castillo MS, Noah ML. Management of severe postpartum hemorrhage with a prostaglandin F2 alpha analogue. Obstet Gynecol 1984;63:806-8.

[24.] Hankins GD, Berryman GK, Scott RT Jr, Hood D. Maternal arterial desaturation with 15-methyl prostaglandin F2 alpha for uterine atony. Obstet Gynecol 1988;72(3 Pt 1):367-70.

[25.] Brar HS, Greenspoon JS, Platt LD, Paul RH. Acute puerperal uterine inversion. New approaches to management. J Reprod Med 1989;34:173-7.

[26.] Catanzarite VA, Moffitt KD, Baker ML, Awadalla SG, Argubright KF, Perkins RP. New approaches to the management of acute puerperal uterine inversion. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68(3 Suppl):TS-105.

[27.] Gross SJ, Shime J, Farine D. Shoulder dystocia: predictors and outcome. A five-year review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987; 156:334-6.

[28.] Modanlou HD, Dorchester WL, Thorosian A, Freeman RK. Macrosomia--maternal, fetal, and neonatal implications. Obstet Gynecol 1980;55:420-4.

[29.] Nocon JJ, McKenzie DK, Thomas LJ, Hansell RS. Shoulder dystocia: an analysis of risks and obstetric maneuvers. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 168:1732-9.

[30.] McFarland M, Hod M, Piper JM, Xenakis EM, Langer O. Are labor abnormalities more common in shoulder dystocia? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 173:1211-4.

[31.] Nesbitt TS, Gilbert WM, Herrchen B. Shoulder dystocia and associated risk factors with macrosomic births in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol [In press].

[32.] Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Souter I, Neumann K, Ouzounian JG, Paul RH. The McRoberts' maneuver for the alleviation of shoulder dystocia: how successful is it? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;176:656-61.

[33.] Douglas KA, Redman CW. Eclampsia in the United Kingdom. BMJ 1994;309:1395-1400.

[34.] Sibai BM, McCubbin JH, Anderson GD, Lipshitz J, Dilts PV Jr. Eclampsia. I. Observations from 67 recent cases. Obstet Gynecol 1981;58:609-13.

[35.] Sibai BM. Eclampsia. VI. Maternal-perinatal outcome in 254 consecutive cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:1049-54.

[36.] Which anticonvulsant for women with eclampsia? Evidence from the Collaborative Eclampsia Trial. Lancet 1995;345:1455-63 [Published erratum in Lancet 1995;346:258].

[37.] Chien PF, Khan KS, Arnott N. Magnesium sulphate in the treatment of eclampsia and pre-eclampsia: an overview of the evidence from randomised trials. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:1085-91.

[38.] Usta IM, Sibai BM. Emergent management of puerperal eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1995;22:315-35.

[39.] Mabie WC, Gonzalez AR, Sibai BM, Amon E. A comparative trial of labetalol and hydralazine in the acute management of severe hypertension complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1987;70(3 Pt 1);328-33.

ELIZABETH H. MORRISON, M.D., M.S.ED., is assistant clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine, College of Medicine. She also serves on the staff of Long Beach (Calif.) Memorial Medical Center. Dr. Morrison is a graduate of Brown University School of Medicine, Providence, R.I. She completed an internship in family medicine at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and a residency in family medicine at Ventura (Calif.) County Medical Center. She also completed a master of medical education degree at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Address correspondence to Elizabeth H. Morrison, M.D., M.S. Ed., Family Medicine Residency, Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, 450 E. Spring St., Suite 1, Long Beach, CA 90806. Reprints are not available from the author.

COPYRIGHT 1998 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group