Background

Definition Generalised anxiety disorder is defined as excessive worry and tension, on most days, for at least six months, together with the following symptoms and signs: increased motor tension (fatiguability, trembling, restlessness, muscle tension); autonomic hyperactivity (shortness of breath, rapid heart rate, dry mouth, cold hands, and dizziness) but not panic attacks; and increased vigilance and scanning (feeling keyed up, increased startling, impaired concentration).

Incidence/prevalence The assessment of the incidence and prevalence of generalised anxiety disorder is problematic. There is a high rate of comorbidity with other anxiety disorders and depressive disorders.[1] Moreover, the reliability of the measures used in epidemiological studies is unsatisfactory.[2] One American study that used the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, revised (DSM-III-R), has estimated that one in every 20 people will develop generalised anxiety disorder at some time during their lives.[3]

Aetiology/risk factors One small community study found that generalised anxiety disorder was associated with an increase in the number of minor stressors, independent of demographic factors.[4] People with generalised anxiety disorder report more somatic symptoms and respond in a rigid, stereotyped manner if placed under physiological stress. Autonomic function is similar to that of control populations, but muscle tension is increased.[5] Whether these findings are cause or effect remains uncertain.

Prognosis Generalised anxiety disorder is a long term condition. It often begins before or during young adulthood and can be a lifelong problem. Spontaneous remission is rare.[3]

Aims To reduce anxiety, to minimise disruption of day to day functioning, and to improve quality of life, with minimum adverse effects.

Outcomes Severity of symptoms and effects on quality of life, as measured by symptom scores, usually the Hamilton anxiety scale or clinical global impression symptom scores. Where numbers needed to treat (NNTs) are given, these represent the number of people requiring treatment within a given time period (usually 6-12 weeks) for one additional person to achieve a certain improvement in symptom score. The method for obtaining NNTs was not standardised across studies. Some used a reduction by, for example, 20 points in the HAM-A as a response, whereas others defined a response as a reduction, for example, by 50% of the premorbid score. We have not attempted to standardise methods but instead have used the response rates reported in each study to calculate NNTs. Similarly, we have calculated numbers needed to harm (NNHs) from original trial data.

Methods Clinical Evidence search and appraisal, November 1999. Recent changes in diagnostic classification make it hard to compare older studies with more recent ones. In the earlier classification system, DSM-III-R, the diagnosis was made only in the absence of other psychiatric disorder. In current systems (DSM-IV and ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision)), generalised anxiety disorder can be diagnosed in the presence of any comorbid condition. All drug studies were short term, at most 12 weeks.

Question: What are the effects of cognitive therapy?

Summary One systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) has found that cognitive therapy, using a combination of behavioural interventions such as anxiety management training, exposure, relaxation, and cognitive restructuring, is more effective than remaining on a waiting list (no treatment), anxiety management training alone, or non-directive therapy. We found no evidence of adverse effects.

Benefits

We found one systematic review (search date 1996), which identified 35 RCTs of medical treatment, cognitive therapy, or both, in 4002 people (60% women).[6] Thirteen trials included 22 cognitive behavioural therapies, which involved (alone or in combination) cognitive restructuring, relaxation training, anxiety management training, exposure, and systematic desensitisation. Combined results from these trials found significantly better results with active treatment than with control treatments (effect size 0.70, 95% confidence interval 0.57 to 0.83). Controls included remaining on a waiting list, anxiety management training, relaxation training, and non-directive psychotherapy. A one year follow up of an RCT found cognitive therapy was associated with better outcomes than analytic psychotherapy and anxiety management training.[6 7]

Harms

We found no evidence of adverse effects.

Comment

None.

Question: What are the effects of drug treatments?

Option: Benzodiazepines

Summary One systematic review of RCTs has found that benzodiazepines are an effective and rapid treatment for generalised anxiety disorder. They carry risk of dependence, sedation, industrial accidents, and road traffic accidents. They should be avoided late in pregnancy and while breast feeding. One RCT found no significant difference between sustained release alprazolam and bromazepam. One RCT found no evidence of a difference in effectiveness between benzodiazepines and buspirone.

Benefits

Versus placebo: We found one systematic review (search date January 1996), which identified 24 placebo controlled trials of drug treatments, principally benzodiazepines (in 19 trials), buspirone (in nine trials), antidepressants (ritanserin and imipramine, in three trials), all in people with generalised anxiety disorder.[6] Pooled analysis across all studies gave an effect size of 0.60 (0.50 to 0.70), whereas for benzodiazepines the mean effect size was 0.70 (95% confidence intervals not given). The review found no significant differences in effect sizes between different benzodiazepines, although there was insufficient power to rule out a clinically important difference. One of the larger trials (n = 230) that was included found that the number of people reporting global improvement after eight weeks (completer analysis, overall dropout rate 35%, no significant difference in withdrawal rates between groups) was greater with diazepam than with placebo (diazepam 67%, placebo 39%, P [is less than] 0.026). Versus each other: One subsequent RCT (n=121) compared sustained release alprazolam versus bromazepam and found no significant difference in effects (Hamilton anxiety scale scores).[8] Versus buspirone: See option.

Harms

Sedation and dependence: Benzodiazepines have been found to cause cognitive impairment in attention, concentration, and short term memory. One of the RCTs included in the systematic review mentioned above found a high rate of drowsiness (71% with diazepam v 13% with placebo, P=0.001) and dizziness (29% v 11%, P=0.001).[6] Sedation can interfere with concomitant psychotherapy. There is a high risk of substance abuse and dependence with benzodiazepines. Rebound anxiety on withdrawal has been reported in 15-30% of participants.[9] Memory: Thirty one people with agoraphobia or panic disorder from a placebo controlled trial of eight weeks' alprazolam were followed up at 3.5 years. Five were still taking benzodiazepines and had significant impairment in memory tasks.[10] There was no difference in memory performance between people who had been in the placebo group and people who had been given alprazolam but were no longer taking the drug. Road traffic accidents: We found one systematic review (search date 1997) examining the relation between benzodiazepines and road traffic accidents.[11] In the case control studies identified, the odds ratio for death or emergency medical treatment in people who had taken benzodiazepines compared with those people who had not taken them ranged from 1.45 to 2.4. The odds ratio increased with higher doses and more recent intake. In the police and emergency ward studies, benzodiazepine use was a factor in 1-65% of accidents (usually 5-10%). In two studies in which participants had blood alcohol concentrations under the legal limit, benzodiazepines were found in 43% and 65%. For drivers over 65 years, the risk of being involved in reported road traffic accidents was higher if they had taken longer acting and larger quantities of benzodiazepines. These studies are retrospective case-control studies and are therefore subject to confounding factors. Pregnancy and breast feeding: One systematic review (search date 1997) identified 23 studies looking at the link between cleft lip and palate and use of benzodiazepines in the first trimester of pregnancy.[12] The review found no association. However, use of benzodiazepines in late pregnancy has been found to be associated with neonatal hypotonia and withdrawal syndrome.[13] Benzodiazepines are secreted in breast milk, and there have been reports of sedation and hypothermia in infants.[13]

Comment

All the benzodiazepine studies were short term (at most 12 weeks) There was usually a significant improvement at six weeks, but response rates were given at the end of the trials. Sustained release preparations could improve adherence to treatment.

Option: Buspirone

Summary RCTs have found that buspirone is effective in generalised anxiety disorder. Limited data provide no evidence of a difference in effectiveness compared with benzodiazepines or antidepressants. Buspirone's slower onset compared with benzodiazepines is counterbalanced by fewer adverse effects.

Benefits

Versus placebo: We found one systematic review (search date January 1996), which identified nine studies of buspirone but did not report on its effects as distinct from pharmacotherapy in general.[7] One of the included studies was itself a non-systematic meta-analysis of eight placebo controlled trials of buspirone in 520 people with generalised anxiety disorder (see comment below). It found that, compared with placebo, buspirone was associated with a greater response rate, defined as the proportion of people much or very much improved as rated by their physician (54% v 28%, P [is less than or equal to] 0.001). A later double blind placebo controlled trial in 162 people with generalised anxiety disorder found similar results (buspirone 55% v placebo 35%, P [is less than] 0.05).[14] Versus benzodiazepines: The systematic review did not directly compare buspirone with benzodiazepines, although one large RCT (n = 230) included in the review found no significant difference between buspirone and benzodiazepines.[6] Versus antidepressants: See below.

Harms

Sedation and dependence: The systematic review found that, compared with benzodiazepines, buspirone had a slower onset of action, but this was counterbalanced by fewer adverse effects) The later RCT found that, compared with placebo, buspirone caused significantly more nausea (34% v 13%), dizziness (64% v 12%), and somnolence (19% v 7%). We found no reports of dependency on buspirone. Pregnancy and breast feeding: We found no data.

Comment

The trials in the meta-analysis mentioned above were all sponsored by pharmaceutical companies and were mainly undertaken for regulatory and licensing purposes to see whether buspirone had antidepressant properties. All the trials examined in the systematic review had been included in the new drug application for buspirone as an antidepressant. Other search criteria were not given. Trial methods were similar.[6]

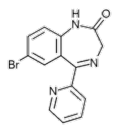

Option: Antidepressants

Summary RCTs have found that imipramine, trazodone, venlafaxine, and paroxetine are effective treatments for generalised anxiety disorder. Individual RCTs found that they were more effective than benzodiazepines, with no evidence of a difference in effectiveness compared with buspirone. There is an appreciable risk of sedation, confusion, and falls with these drugs. There is a high risk of arrhythmia in overdose with imipramine.

Benefits

Versus placebo: We found one systematic review (search date January 1996, three placebo controlled RCTs of antidepressants) which found treatment to be significantly associated with a greater response than placebo (pooled effect size 0.57).[6] The review pooled results for trazodone, imipramine, and ritanserin, so limiting the conclusions that may be drawn for trazodone and imipramine alone.[6] In another placebo controlled RCT in 230 people, the NNT for moderate or pronounced improvement after eight weeks of treatment with imipramine was 3 (completer analysis calculated from data by author) and with trazodone the NNT was 4 (95% confidence interval 3 to 4, calculated from data by author).[15] Versus benzodiazepines: We found one RCT comparing paroxetine, imipramine, and 2'-chlordesmethyl-diazepam for eight weeks in 81 people with generalised anxiety disorder.[16] Paroxetine and imipramine were significantly more effective than 2'-chlordesmethyldiazepam in improving anxiety scores (mean Hamilton anxiety scale score after eight weeks, 11.1 for paroxetine, 10.8 for imipramine, 12.9 for 2'-chlordesmethyldiazepam, P = 0.05). Versus buspirone: We found no systematic review. We found one RCT (n=365) comparing venlafaxine 75 mg/day and 150 mg/day versus buspirone 30 mg/day over eight weeks, with a small placebo arm. There was no significant difference between the two treatments (venlafaxine 75 mg, NNT 8, 6 to 9; venlafaxine 150 mg, NNT 7.3, 6 to 9; busperone 30 mg, NNT 11, 10 to 12).[17] Sedating tricyclic antidepressants: We found no systematic review or RCTs evaluating sedating tricyclics in people with generalised anxiety disorder.

Harms

Sedation, confusion, dry mouth, and constipation have been reported with both imipramine and trazodone.[15] Overdose: In a series of 239 necropsies directed by coroners from 1970 to 1989, tricyclic antidepressants were considered to be a causal factor in 12% of deaths and hypnosedatives (primarily benzodiazepines and excluding barbiturates) in 8%.[18] Accidental poisoning: From 1958 to 1977 a total of 598 deaths in British children under the age of 10 years were registered as accidental poisoning. After 1970, tricyclic antidepressants were the most common cause of accidental poisoning in this age group.[19] A study estimated that there was one death for every 44 children admitted to hospital after ingestion of tricyclic antidepressants.[20] Hyponatraemia: A case series reported 736 incidents of hyponatraemia in people taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); 83% of episodes were in hospital inpatients aged over 65 years.[21] It is not possible to establish causation from this type of data. Nausea: Nausea has been reported in people taking paroxetine.[16] Falls: A retrospective cohort study of 2428 elderly residents of nursing homes found an increased risk of falls in new users of antidepressants (adjusted relative risk for tricyclic antidepressants: 2.0, 1.8 to 2.2, n = 665; for SSRIs: 1.8, 1.6 to 2.0, n = 612; and for trazodone: 1.2, 1.0 to 1.4, n = 304).[22] The increased rate of falls persisted through the first 180 days of treatment and beyond. A case-control study of 8239 people aged 66 years or older treated in hospital for hip fracture found an increased risk of hip fracture in those taking antidepressants.[23] The adjusted odds ratio for hip fracture compared with that in those not taking antidepressants was 2.4 (2.0 to 2.7) for SSRIs, 2.2 (1.8 to 2.8) for secondary amine tricyclic antidepressants such as nortriptyline, and 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) for tertiary amine tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline. This study could not control for confounding factors; people taking antidepressants may be at increased risk of hip fracture for other reasons. In pregnancy: We found no reports of harmful effects in pregnancy. One case controlled study found no evidence that imipramine or fluoxetine increased the rate of malformations in pregnancy.[24]

Comment

None.

Option: Antipsychotic drugs

Summary One brief RCT found that trifluoperazine was effective in low dose but carried significant risk of serious adverse effects.

Benefits

We found no systematic review. We found one RCT comparing four weeks of treatment with trifluoperazine 2-6 mg/day versus placebo in 415 people with generalised anxiety disorder.[25] The trial reported an average reduction of 14 points on the total anxiety rating scale (Hamilton anxiety scale), with no reduction in those receiving placebo (p [is less than] 0.001).

Harms

Short term treatment with antipsychotic drugs carries a significant risk of sedation, acute dystonias, akathisia, and parkinsonism. In the longer term, the rate of tardive dyskinesia may be increased, especially if treatment is interrupted.[26]

Comment

None.

Option: [Beta] Blockers

Summary [Beta] Blockers have not been adequately evaluated in people with generalised anxiety disorder.

Benefits

We found no systematic review or good RCTs of [Beta] blockers in people with generalised anxiety disorder.

Harms

Inadequate data in people with generalised anxiety disorder.

Comment

None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Interventions

Beneficial:

Cognitive therapy

Likely to be beneficial:

Buspirone

Certain antidepressants (paroxetine, imipramine, trazodone, venlafaxine, mirtazepine)

Trade off:

Benzodiazepines

Unknown effectiveness:

Antipsychotic drugs

[Beta] Blockers

[1] Judd LL, Kessler RC, Paulus MP, et al. Comorbidity as a fundamental Feature of generalised anxiety disorders: results from the national comorbidity study (NCS). Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998;98(suppl 393):6-11.

[2] Andrews G, Peters L, Guzman AM, Bird K. A comparison of two structured diagnostic interviews: CIDI and SCAN. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1995;29:124-32.

[3] Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;51:8-19.

[4] Brantley PJ, Mehan DJ, Ames SC, Jones GN. Minor stressors and generalised anxiety disorder among low-income patients attending primary care clinics. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:435-40.

[5] Hoehn-Saric R. Psychic and somatic anxiety: worries, somatic symptoms, and physiological changes. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998:98(suppl 393);32-8.

[6] Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH, Yap L. Cognitive behavioural and pharmacological treatment of generalised anxiety disorder: a preliminary meta-analysis. Behav Ther 1997;28:285-305.

[7] Durham RC, Fisher PL, Trevling LR, Hau CM, Richard K, Stewart JB. One year follow-up of cognitive therapy, analytic psychotherapy and anxiety management training for generalised anxiety disorder: symptom change, medication usage and attitudes to treatment. Behav Cogn Psychother 1999;27:19-35.

[8] Figueira ML. Alprazolam SR in the treatment of generalised anxiety: a multicentre controlled study with bromazepam. Hum Psychother 1999;14:171-7.

[9] Tyrer P. Current problems with the benzodiazepines. In: Wheatly D, ed. The anxiolytic jungle: where next? Chichester: Wiley, 1990:23-60.

[10] Kilic C, Curran HV, Noshirvani H, Marks IM, Basoglu MB. Long-term effects of alprazloam on memory: a 3.5 year follow-up of agoraphobia/ panic patients. Psychol Med 1999;29:225-31.

[11] Thomas RE. Benzodiazepine use and motor vehicle accidents. Systematic review of reported association. Can Fam Physician 1998;44:799-808.

[12] Dolovich LR, Addis A, Regis Vaillancourt JD, et al. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations of oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998;317:839-843.

[13] Bernstein JG. Handbook of drug therapy in psychiatry. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby Year Book, 1995:401.

[14] Sramek JJ, Transman M, Suri A, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in generalized anxiety disorder with coexisting mild depressive symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:287-91.

[15] Rickels K, Downing R, Schweizer E, Hassman H. Antidepressants for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine, trazodone and diazepam. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:884-95.

[16] Rocca P, Fonzo V, Scotta M, Zanalda E, Ravizza L. Paroxetine efficacy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997;95:444-50.

[17] Davidson JR, DuPont RL, Hedges D, Haskins JT. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of venlafaxine extended release and busperone in outpatients with generalised anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999:60;528-35.

[18] Dukes PD, Robinson GM, Thomson KJ, Robinson BJ. Wellington coroner autopsy cases 1970-89: acute deaths due to drugs, alcohol and poisons. N Z Med J 1992;105:25-27. (Published erratum appears in N Z Med J 1992;105:135.)

[19] Fraser NC. Accidental poisoning deaths in British children 1958-77. BMJ 1980;280:1595-8.

[20] Pearn J, Nixon J, Ansford A, Corcoran A. Accidental poisoning in childhood: five year urban population study with 15 year analysis of fatality. BMJ 1984;288:44-6.

[21] Lui BA, Mitmann N, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Hyponatremia and the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone associated with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a review of spontaneous reports. Can Med Assoc J 1996;155:519-27.

[22] Thapa PB, Gideon P, Cost TW, Milam AB, Ray WA. Antidepressants and the risk of falls among nursing home residents. N Engl J Med 1998;339:875-82.

[23] Liu B, Anderson G, Mittmann N, To T, Axcell T, Shear N. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors of tricyclic antidepressants and risk of hip fractures in elderly people. Lancet 1998;351:1303-7.

[24] Kulin NA, Pastuszak A, Koren G. Are the new SSRIs safe for pregnant women? Can Fam Phys 199844:2081-3.

[25] Mendels J, Krajewski TF, Huffer V, et al. Effective short-term treatment of generalized anxiety with trifluoperazine. J Clin Psychiatry 1986;47:170-4.

[26] Van Harten PN, Hoek HW, Matroos GE, Koeter M, Kahn RS. Intermittent neuroleptic treatment and risk of tardive dyskinesia: Curacao extrapyradimal syndromes study III. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:565-7.

Clinical Evidence is published by BMJ Publishing Group. The third issue is available now, and Clinical Evidence will be updated and expanded every six months. The next issue will be available in December. Individual subscription rate, issues 3 and 4 75 [pounds sterling]/$140; institutional rate 160 [pounds sterling]/$245. For more information including how to subscribe, please visit the Clinical Evidence website at www.clinical evidence.org

University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Christopher Gale psychiatrist

Mark Oakley-Browne associate professor

Correspondence to: C Gale, Division of Psychiatry, University of Auckland, 4th Floor, 3 Ferncroft St, Grafton, Auckland 1003, New Zealand c.gale@auckland. ac.nz

BMJ 2000;321:1204-7

If you are interested in being a contributor or peer reviewer for Clinical Evidence please visit the Clinical Evidence website (www.clinical evidence.org)

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group