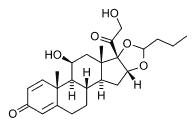

Background: We evaluated the efficacy and safety of low-dose budesonide/formoterol, 80 [micro]g/4.5 [micro]g, bid in a single inhaler (Symbicort Turbuhaler; AstraZeneca; Lund, Sweden) compared with an increased dose of budesonide, 200 [micro]g bid, in adult patients with mild-to-moderate asthma not fully controlled on low doses of inhaled corticosteroid alone.

Methods: All patients received budesonide, 100 100g bid, during a 2-week run-in period. At the end of the run-in phase, 467 patients with a mean FE[V.sub.1] of 82% predicted received 12 weeks of treatment with budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler or budesonide alone in a higher dose. Patients kept daily records of their morning and evening peak expiratory flow (PEF), nighttime and daytime symptom scores, and use of reliever medication.

Results: The increase in mean morning PEF--the primary efficacy measure--was significantly higher for budesonide/formoterol compared with budesonide alone (16.5 L/min vs 7.3 L/min, p = 0.002). Similarly, evening PEF was significantly greater in the budesonide/formoterol group (p < 0.001). In addition, the percentage of symptom-free days and asthma-control days (p = 0.007 and p = 0.002, respectively) were significantly improved in the budesonide/formoterol group. Budesonide/formoterol decreased the relative risk of an asthma exacerbation by 26% (p = 0.02) compared with budesonide alone. Adverse events were comparable between the two treatment groups.

Conclusion: This study shows that in adult patients whose mild-to-moderate asthma is not fully controlled on low doses of inhaled corticosteroids, single-inhaler therapy with budesonide and formoterol provides greater improvements in asthma control than increasing the maintenance dose of inhaled corticosteroid.

Key words: asthma; budesonide; formoterol; inhaled corticosteroids; long-acting [[beta].sub.2]-agonists; Symbicort

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OPTIMA = Optimal Treatment for Mild Asthma; PEF = peak expiratory flow

**********

In patients with persistent asthma who remain symptomatic on a low dose of inhaled corticosteroids, current treatment guidelines advise increasing the dose of inhaled corticosteroid to a moderate dose before considering the addition of a long-acting [[beta].sub.2]-agonist. (1) Several studies show that the combined use of long-acting [[beta].sub.2]-agonists with low-to-moderate doses of inhaled corticosteroid therapy appears to provide greater clinical benefit than further increasing the dose of inhaled corticosteroid. (2-6) Pauwels and colleagues (7) showed that in patients with moderate asthma, the addition of formoterol, 12 [micro]g bid, to low-dose corticosteroids improved lung function to a greater extent over a 12-month period than a fourfold increase in corticosteroids alone. Moreover, the addition of formoterol led to a decrease in asthma exacerbations, (7) and a second 1-year study (8) showed that there was no change in inflammatory markers in patients treated with low-dose budesonide plus formoterol compared with patients treated with a fourfold increase in budesonide. Based on the complementary efficacy benefits obtained by adding formoterol to low doses of budesonide, and the patient benefits resulting from simplifying asthma therapy, a single inhaler containing budesonide and formoterol (Symbicort Turbuhaler; AstraZeneca; Lund, Sweden) has recently become available, and this carries the advantage of simplifying asthma therapy and combining two complementary medications.

A previous study (9) in patients with moderate-to-severe asthma showed that budesonide/formoterol, 160 [micro]g/4.5 [micro]g (two inhalations bid), improved lung function and asthma control to a similar extent as equivalent doses of budesonide and formoterol administered via separate inhalers. However, a lower dose of formoterol, 4.5 [micro]g bid, has been shown to provide bronchodilation for at least 12 h. (10-12) Therefore, in the present study, we examined the hypothesis that patients with mild-to-moderate asthma not fully controlled on low doses of inhaled corticosteroids would derive greater improvements in lung function and asthma control with low-dose budesonide/formoterol, 80 [micro]g/4.5 [micro]g bid, compared with a higher maintenance dose of budesonide, 200 [micro]g bid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, multinational study conducted at 51 centers in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Norway, Poland, South Africa, Sweden, and United Kingdom. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulations, each study center having received ethical approval of the protocol prior to study commencement. All patients gave written informed consent.

Study Design

Male and female patients aged [greater than or equal to] 18 years with a diagnosis of asthma (minimum duration, 6 months), FE[V.sub.1] of 60 to 90% of the predicted normal value, and [greater than or equal to] 12% reversibility of basal FE[V.sub.1] within 15 min of inhalation of terbutaline or salbutamol ([less than or equal to] 1 mg) were eligible for inclusion. All patients used inhaled corticosteroids (any brand) at a constant dose (200 to 500 [micro]g/d) for at least 1 month prior to study entry. Exclusion criteria included use of oral, parenteral, or rectal corticosteroids within 30 days of study commencement, any respiratory infection affecting disease control within the previous 4 weeks, and known hypersensitivity to study medication or inhaled lactose. Patients with severe cardiovascular disorders or other significant concomitant diseases, and current and previous smokers with a history of smoking for [greater than or equal to] 10 pack-years were not eligible for inclusion. All female patients were required to be postmenopausal, surgically sterile, or using an adequate contraceptive method throughout the study.

Patients received budesonide, 100 [micro]g bid, for an open, 2-week run-in period, during which time baseline data were collected. Patients were then randomized to 12 weeks of twice-daily inhaled treatment with either budesonide/formoterol, 80 [micro]g/4.5 [micro]g, or budesonide, 200 [micro]g. Inhaled terbutaline or salbutamol, depending on patient preference, was used as reliever medication by each patient throughout the study. Treatment with systemic antihistamines, [beta]-blockers, or other antiasthma products was not permitted. Other medication considered necessary for the patients' well-being was administered at the discretion of the investigator. Adherence to therapy was assessed by reviewing patient diary cards.

Efficacy Evaluations

After careful instruction, patients measured their own morning and evening peak expiratory flow (PEF) using a Mini-Wright peak flowmeter (Clement Clark; Harlow, UK). All measurements were to be made prior to the inhalation of reliever or study medication, and the highest value of three consecutive measurements was recorded. Patients noted the severity of both daytime and nighttime asthma symptoms on a scale from 0 to 3 (0 = no symptoms, 1 = mild symptoms, 2 = moderate symptoms, 3 = severe symptoms), use of reliever medication, and nighttime awakenings due to asthma symptoms.

Spirometry measurements were determined at screening, randomization (baseline), and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment. Patients were asked to avoid the use of reliever medication 6 h prior to testing. In addition, they were asked to refrain from exercise for 2 h and from smoking for at least 1 h prior to spirometry testing. Three satisfactory tests were required, from which the highest values for FE[V.sub.1] and FVC were recorded. FE[V.sub.1] as a percentage of the predicted normal value was calculated according to standard methods. (13)

Clinical Safety Assessments

All adverse events, both spontaneously reported or reported in response to a standard question asked by the investigator, were recorded at clinic visits.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of this study was to compare the efficacy of twice-daily, low-dose budesonide/formoterol, 80 [micro]g/4.5 [micro]g, with a higher twice-daily budesonide dose, 200 [micro]g, over a 12-week treatment period. Efficacy analyses were carried out on all randomized patients (intention-to-treat approach). For morning PEF and other patient diary variables, analyses were performed in terms of the change from baseline to treatment. Baseline was defined as the average value over the last 10 days of run-in and treatment as the average value for the entire treatment period. These values were submitted to analysis of variance with treatment and country, and treatment and country interaction as factors and baseline measurements of the dependent variable as covariate. The treatment differences were weighted over countries according to precision. For spirometry, measurements obtained at the randomization visit were used as baseline values, and the logarithm of the last available measurement on treatment was subjected to an analysis of variance similar to the one for diary card variables.

A symptom-free day was defined as a night and a day with no asthma symptoms and no nighttime awakenings. As an overall measure of symptom control, the percentage of symptom-free days and of reliever-free days was determined. Combining these end points allowed for the determination of asthma-control days (defined as a night and a day without symptoms, no intake of reliever medication, and no asthma-related nighttime awakenings).

Finally, the time to first mild and first severe exacerbation was analyzed using a log-rank test, and further described with a Cox proportional hazards model. A mild exacerbation was defined as two consecutive mild exacerbation days (of the same criterion), the latter being defined as nighttime awakening due to asthma, a 20% decrease in PEF from baseline, or more than four inhalations of reliever medication over a 24-h period. A severe exacerbation was defined as the need for oral steroids, or a [greater than or equal to] 30% decrease in PEF from baseline on 2 consecutive days, or discontinuation due to asthma worsening.

RESULTS

Of the 494 patients who entered the open 2-week run-in period, 467 patients (200 men and 267 women) aged 18 to 78 years (mean, 41 years) were randomized to the study. A total of 37 patients discontinued the study: 15 patients in the budesonide/formoterol group (6 with asthma deterioration, 3 with adverse events, and 6 for other reasons) and 22 patients in the budesonide-alone group (5 with asthma deterioration, 3 with adverse events, and 14 for other reasons).

Overall, baseline demographics and baseline clinical characteristics were similar for the two treatment groups (Tables 1, 2). Mean FE[V.sub.1] at randomization was similar in both groups (Table 1), and 55% of all patients had a baseline FE[V.sub.1] measurement exceeding 80% of the predicted normal value. A review of patient diaries showed that the majority of patients had asthma that was not well controlled, as evidenced by the fact that 75% used reliever medications and 44% reported nighttime awakenings over the last 10 days of the run-in period. Self-reported adherence to study medication was high (mean > 97%) in both treatment groups.

Lung Function

Mean morning and evening PEF improved in both treatment groups over the 12-week study. There was a significantly greater increase in morning PEF and evening PEF in patients treated with budesonide/ formoterol compared with those treated with a higher dose of budesonide (Table 2). The increases observed in morning and evening PEF in patients treated with budesonide/formoterol were apparent from the first day of treatment and were maintained throughout the 12-week study (Fig 1, top, a, and bottom, b). During the study, mean FE[V.sub.1] increased from baseline values in both treatment groups. A comparison of the ratios of geometric means from a multiplicative model showed no significant between-group differences, whereas mean FVC showed no appreciable change from baseline for either treatment group.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

Symptoms

Significant differences in favor of budesonide/ formoterol therapy were observed over the 12-week period for asthma-control days, symptom-free days, and use of reliever medication. The proportion of asthma-control days increased by 17% in the budesonide/formoterol group and by 10% in the higher-dose budesonide group (Fig 2). The estimated between-group difference and 95% confidence interval (CI) for asthma-control days was 8% (95% CI, 3 to 13%) in favor of budesonide/ formoterol (p = 0.002). Similar improvements were seen in the proportion of symptom-free days (16% vs 10% for budesonide/formoterol and budesonide, respectively). The estimated between-group difference for symptom-free days was 6% (95% CI, 2 to 11%) in favor of budesonide/ formoterol (p = 0.007). Reductions from the run-in baseline of 24% vs 6% for asthma symptom score and 23% vs 14% for nighttime awakenings were observed in patients treated with budesonide/formoterol vs budesonide, respectively. This was reflected in a significantly greater reduction in reliever medication use in patients treated with budesonide/formoterol compared with those receiving budesonide (p = 0.025; Table 2).

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

Exacerbations of Asthma

Fewer patients in the budesonide/formoterol group (110 of 230 patients) experienced at least one mild asthma exacerbation compared with those in the budesonide group (136 of 237 patients). The number of patients with repeated nighttime awakenings due to their asthma was the key factor differentiating in favor of budesonide/formoterol (75 patients vs 105 patients, budesonide/formoterol vs budesonide). The probability of patients remaining free from a mild exacerbation throughout the study is shown in Figure 3. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves show clear separation in favor of budesonide/formoterol, with increasing separation over time. In addition, patients in the budesonide group had a shorter time to first mild exacerbation than the budesonide/ formoterol-treated patients (p = 0.02, log-rank test). A subsequent Cox proportional hazards model indicated that the estimated relative risk of having a mild asthma exacerbation was 26% lower for patients treated with budesonide/formoterol (p = 0.02). The estimated risk of having a severe exacerbation using the Cox proportional hazards model was 6% lower in patients treated with budesonide/formoterol compared with those receiving budesonide alone, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.85). There were no between-group differences in the proportion of patients with severe exacerbations (7% in both treatment groups) or in the time to first severe exacerbation.

[FIGURE 3 OMITTED]

Adverse Events

Patients who received at least one dose of study medication were included in the safety analysis (n = 467). Overall, no between-group differences were apparent in terms of the profile and frequency of all reported adverse events (whether or not drug related) [Table 3]. The most common adverse events in both treatment groups were respiratory infection, pharyngitis, and rhinitis, which were generally of mild-to-moderate intensity. Undesirable class effects of [[beta].sub.2]-agonists, such as headache, palpitations, and tremor, were infrequent in the budesonide/formoterol group ([less than or greater than] 2% of patients). There were no reports of oral candidiasis or dysphonia among those treated with budesonide alone.

One serious adverse event (asthma aggravation) reported was considered by the investigator to be causally related to treatment. In total, there were seven serious adverse events: five with budesonide/ formoterol (appendicitis, fracture, joint dislocation, paralysis, asthma aggravation) and two with budesonide (cholecystitis, neuralgia).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that patients with mild-to-moderate asthma not fully controlled on low doses of inhaled corticosteroid (200 [micro]g/d) benefit significantly from treatment with low-dose budesonide/ formoterol compared with raising the dose of corticosteroid alone. These results provide further evidence in support of adding a long-acting [[beta].sub.2]-agonist to low-dose inhaled corticosteroid before increasing the dose of inhaled corticosteroid in patients who are not fully controlled on their current dose of corticosteroids. In addition, this study is the first to suggest a role for low-dose maintenance treatment with both budesonide and formoterol via a single inhaler in patients with mild-to-moderate asthma.

There was a significantly greater increase in both morning and evening PEF with budesonide/formoterol compared with an increased dose of inhaled corticosteroid alone. Moreover, there were also increases in symptom-free days and asthma-control days and a reduction in the need for reliever bronchodilator after treatment with budesonide/formoterol. There was no evidence of deterioration in asthma control with low-dose budesonide/formoterol in comparison to the higher maintenance dose of budesonide. Indeed, a significant reduction in mild asthma exacerbations was observed in patients treated with budesonide/formoterol compared with the higher maintenance dose of inhaled corticosteroid.

The Optimal Treatment for Mild Asthma (OPTIMA) randomized trial (14) showed that the addition of formoterol to low-dose budesonide improved all asthma outcome variables compared with doubling the dose of inhaled budesonide in patients who were receiving low-dose corticosteroid ([less than or equal to] 400 [micro]g of budesonide) on entry into the study. These findings concur with the present study. The present study used budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler, and the dose of budesonide was 160 [micro]g/d, whereas the OPTIMA study used 200 [micro]g/d. However, patients in the OPTIMA study who had not received corticosteroids for at least 3 months before entering the study only demonstrated an improvement in lung function and not the other outcome variables when formoterol was added to low-dose budesonide. (14) The likely explanation is that this group of patients had very mild asthma for whom low-dose budesonide was optimal. These findings support contemporary adult asthma guidelines that recommend the addition of long-acting [[beta].sub.2]-agonists when asthma is not controlled on low-dose inhaled corticosteroids, and that it is not necessary to use long-acting [[beta].sub.2]-agonists as first-line therapy.

In more moderate-to-severe asthma, a combination of formoterol and low-dose budesonide administered via separate inhalers over 12 months significantly increased morning and evening PEF to a greater extent than a fourfold increase of budesonide. (7) Nevertheless, the higher dose of budesonide was necessary to prevent repeated severe exacerbations. (7) In the population with mild-to-moderate asthma enrolled in our study, using similar exacerbation definitions as Pauwels and colleagues, (7) only 7% of patients in each group had a severe exacerbation; however, approximately half of all patients had at least one mild exacerbation primarily as a result of 2 or more consecutive nights with nighttime awakenings. Our results suggest that low-dose budesonide/formoterol significantly reduces the risk of such exacerbations compared to an increase in the maintenance dose of inhaled corticosteroid. In patients with troublesome nighttime symptoms on a low dose of corticosteroids, current asthma guidelines advocate an up-titration of the inhaled corticosteroid before consideration of additional controller treatment. (1,15,16) The results of this study suggest that even in mild disease, budesonide/formoterol more closely approaches the desired treatment goals of good asthma management than increasing inhaled corticosteroids.

The benefits demonstrated with low-dose budesonide/formoterol in mild-to-moderate asthma were obtained without increasing the use of rescue medication or further increasing inhaled corticosteroid therapy. This alternative approach to treatment should therefore prove attractive to both doctors and patients while providing the convenience of single regular inhaler therapy. The low-close budesonide/ formoterol used in this study was up to four times lower than the dose of monoproducts shown to be effective and safe in long-term efficacy studies in patients with more severe asthma. (7,17) This raises the possibility of stepping-up the dose of budesonide/ formoterol in periods of worsening asthma and stepping-down the dose when asthma is stabilized without the need to change asthma inhalers. Two studies (18,19) support the role for temporary increases in daily doses of either budesonide or formoterol during a period of asthma worsening. Foresi et al (18) showed that in a 6-month study, patients treated with low-dose budesonide plus a temporary increase in dose during exacerbations had a reduced requirement of oral corticosteroids compared with low-dose budesonide alone. Furthermore, a similar reduced requirement for oral corticosteroids and level of asthma control was achieved in these patients compared with the patients maintained on high-dose therapy. Support for temporarily increasing the formoterol component of budesonide/formoterol during periods of worsening in asthma is also provided by the results of a recent study. (19) Formoterol, 4.5 [micro]g, taken as needed, in addition to regular corticosteroid therapy, decreased the risk of severe asthma exacerbations, including the need for oral corticosteroids by 38% compared to the control group using as needed short-acting bronchodilator therapy. (19) Our study demonstrates the benefits of low-dose budesonide/ formoterol compared with a higher dose of budesonide and provides justification for low-dose maintenance therapy with both budesonide and formoterol in a single inhaler. The concept of stepping-up and stepping-down both anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator treatment with budesonide/formoterol in the management of asthma warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, treatment with low-dose budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler improved lung function and provided greater overall asthma control than increasing the dose of inhaled corticosteroid in adults with mild-to-moderate asthma. The efficacy of a lower dose of formoterol widens the safety margin of the combination, thus facilitating the possibility of its use as rescue/as-needed medication in asthma. The data from this study add to the accumulating evidence that addition of a long-acting [[beta].sub.2]-agonist is preferable to increasing the dose of inhaled corticosteroids in symptomatic asthmatics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The authors thank Caroline Hewitt for coordinating the data from AstraZeneca and author contributions from the seven countries in this multinational study, and the patients in the 51 participating centers in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Norway, Poland, South Africa, Sweden, and United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

(1) National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Global initiative for asthma: pocket guide for asthma management and prevention. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1998; publication No. 96-3659B

(2) Greening AP, Ind PW, Northfield M, et al. Added salmeterol versus higher-dose corticosteroid in asthma patients with symptoms on existing inhaled corticosteroid. Lancet 1994; 344:219-224

(3) Woolcock A, Lundback B, Ringdal N, et al. Comparison of addition of salmeterol to inhaled steroids with doubling the dose of inhaled steroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 153:1481-1488

(4) Van Noord JA, Schreurs JM, Mol SJM, et al. Addition of salmeterol versus doubling the dose of fluticasone in patients with mild to moderate asthma. Thorax 1999; 54:207-212

(5) Matz J, Emmett A, Rickard K, et al. Addition of salmeterol to low dose fluticasone: an analysis of asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 107:783-789

(6) Jenkins C, Woolcock AJ, Saarelainen P, et al. Salmeterol/ fluticasone propionate combination therapy 50/250 mcg twice daily is more effective than budesonide 800 mcg twice daily in treating moderate to severe asthma. Respir Med 2000; 94: 715-723

(7) Pauwels RA, Lofdahl C-G, Postma DS, et al. Effect of inhaled formoterol and budesonide on exacerbations of asthma. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1405-1411

(8) Kips JC, O'Connor J, Inman MD, et al. A long-term study of the antiinflammatory effect of low-dose budesonide plus formoterol versus high-dose budesonide in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161:996-1001

(9) Zetterstrom O, Buhl R, Mellem H, et al. Improved asthma control with budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler, compared with budesonide alone. Eur Respir J 2001; 18:262-268

(10) Palmqvist M, Persson G, Lazer L, et al. Inhaled dry-powder formoterol and salmeterol in asthmatic patients: onset of action, duration of effect and potency. Eur Respir J 1997; 10:2484-2489

(11) Schreurs AJ, Sinninghe Damste HE, de Graaff CS, et al. A dose-response study with formoterol Turbuhaler as maintenance therapy in asthmatic patients. Eur Respir J 1996; 9:1678-1683

(12) Ekstrom T, Ringdal N, Tukiainen P, et al. A 3-month comparison of formoterol with terbutaline via turbuhaler: a placebo-controlled study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998; 81:225-230

(13) Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, et al. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows: Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal; Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl 1993; 16:5-40

(14) O'Byrne PM, Barnes PJ, Rodruiguez-Roisin R, et al. Low dose inhaled budesonide and formoterol in mild persistent asthma: the OPTIMA randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164:1392-1397

(15) British guidelines on asthma management: 1995 review and position statement. Thorax 1997; 52(suppl 1):S2-S21

(16) National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 2: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1007; publication No. 97-4051

(17) van der Molen T, Postma DS, Turner MO, et al. Effects of the long acting [beta] agonist formoterol on asthma control in asthmatic patients using inhaled corticosteroids. Thorax 1997; 52:535-539

(18) Foresi A, Morelli MC, Catena E. Low-dose budesonide with the addition of an increased dose during exacerbations is effective in long-term asthma control. Chest 2000; 117:440-446

(19) Tattersfield AE, Lofdahl C-G, Postma DS, et al. Comparison of formoterol and terbutaline in moderate asthma [abstract]. Am J Crit Care Med 1999; 159:A636

* From the Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine (Dr. Lalloo), University of Natal, Durban, South Africa; Medical Academy (Dr. Malolepszy), Wroclaw, Poland; Koranyi National Institute of Tuberculosis and Pulmonology (Dr. Kozma), Budapest, Hungary; Thomayer Teaching Hospital(Dr. Krofta), Prague, Czech Republic; Lund University Hospital (Dr. Ankerst), Lund, Sweden; University Hospital (Dr. Johansen), Oslo, Norway; and Western Infirmary (Dr. Thomson), Glasgow, United Kingdom.

This work was funded by AstraZeneca, Lund, Sweden.

Professor Lalloo was sponsored by AstraZeneca to resent the data from this study at the European Respiratory Society meeting in Berlin 2001. Professor Thomson has received funding from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline to attend meetings of the American Thoracic Society, and funding from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, and Merck for a member of staff to attend scientific meetings. Professor Thomson has also received research funds for clinical trials from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Merck.

Manuscript received December 21, 2001; revision accepted November 12, 2002.

Correspondence to: Umesh G. Lalloo, MD, FCCP, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, University of Natal, Private Bag 7, Congella 4013, Durban, South Africa; e-mail: lalloo@nu.ac.za

COPYRIGHT 2003 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group