Find out more about this common disorder, from assessing symptoms to answering your patient's questions about the newest treatments.

JOHN REED, 49, visits his primary care provider complaining of increasing shortness of breath and fatigue. He has no previous health problems and says his symptoms are worse after such activities as climbing stairs. At first, he attributed his symptoms to "just getting older," but now he's not so sure.

Mr. Reed's primary care provider diagnoses heart failure, a condition he shares with nearly 5 million Americans. An estimated 500,000 new cases are diagnosed every year, and treatment costs $500 million annually.

What is heart failure?

The term heart failure describes the heart's inability to keep up with the body's demand for oxygen. Chronic, progressive, and ultimately fatal, this complex clinical syndrome can be caused by structural or functional cardiac disorders or systemic influences that impair ventricular function. Whether the cause is systolic or diastolic dysfunction (or a combination of the two), the result is reduced cardiac output.

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, the most common type of heart failure, is characterized by reduced stroke volume, incomplete ventricular emptying, cardiac dilation, and elevated left ventricular diastolic pressure. The reduced cardiac output evokes compensatory neurohormonal responses that increase heart rate, sodium and water retention, and vasoconstriction.

In response to injuries in myocardial cells as well as elsewhere in the body, the body mounts an immune response. However, excessive amounts of cytokines and tumor necrosis factor alpha cause more inflammation and damage, contributing to progressive heart failure.

The left ventricle also changes size and shape (called remodeling) to compensate for the decreased cardiac output. Ventricular dilation (in response to increased end-diastolic volume) eventually reduces myocardial contractility. As the heart works at higher volumes and higher filling pressures to maintain cardiac output, fluid moves into the lungs, causing pulmonary congestion and eventual right-sided heart failure.

Diastolic dysfunction, which is less common, is characterized by a stiffened left ventricle that can't relax and fill sufficiently at normal diastolic pressure. The result is either decreased left ventricular end-diastolic volume (leading to decreased cardiac output) or a compensatory rise in left ventricular filling pressure, which can lead to pulmonary venous hypertension.

Recognizing the problem

The most common symptoms of heart failure are dyspnea and fatigue. Other signs and symptoms include exercise intolerance and fluid retention. But some patients have no symptoms or describe symptoms of another cardiac or non-cardiac disorder. Heart failure signs and symptoms can mimic those of pulmonary or cardiac disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, valvular heart disease, or cardiac arrhythmias. Differentiating between systolic and diastolic dysfunction also is important so the health care provider can prescribe the best treatment.

Conduct a thorough patient history and physical assessment, being alert for clues to potential causes of heart failure (see What Can Cause Heart Failure?).

What diagnostic tests reveal

Besides a thorough history and physical exam, Mr. Reed will undergo some or all of the following tests to determine if he has heart failure. These tests also can identify or rule out other cardiac and noncardiac disorders that may cause heart failure or contribute to worsening heart failure.

* A chest X-ray can determine if he has cardiac enlargement or pulmonary congestion and can help identify pulmonary disease. Cardiomegaly indicates systolic dysfunction; a normal heart size suggests diastolic dysfunction.

* A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) can help determine the presence of cardiac arrhythmias, left ventricular hypertrophy, and previous or current myocardial infarction. If the patient has left ventricular dysfunction, the ECG usually will indicate a left ventricular electrical abnormality specific to ventricular dilation or hypertrophy.

* A two-dimensional echocardiogram with Doppler flow study is a noninvasive test to look for structural cardiac abnormalities and to measure ejection fraction. An ejection fraction of less than 40% indicates systolic dysfunction; an ejection fraction greater than 40% with signs and symptoms of heart failure and impaired ventricular relaxation indicates diastolic dysfunction.

* Lab tests that may help diagnose heart failure include complete blood cell count, electrolyte levels (including calcium and magnesium), blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum glucose, serum albumin, liver function tests, thyroid-stimulating hormone, urinalysis, and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). High BNP levels (greater than 100 pg/ml) accompany abnormal ventricular function or symptomatic heart failure.

* A right-sided heart catheterization also can be performed to determine the heart's preload pressures and pulmonary pressures to determine the degree of heart failure and the need for further intervention. A patient with angina who's a candidate for coronary revascularization may undergo a full cardiac catheterization with coronary arteriography.

All the world's a stage

Because heart failure is a progressive disease, staging systems are used to classify the patient's risks and symptoms and to guide therapy. The New York Heart Association classifications are based on the patient's functional abilities. The newer American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines promote prevention and treatment strategies and are based on cardiac structural defects as well as risk factors and symptoms. For more details, see Two Ways of Looking at Heart Failure.

Talking about treatment

Treatment for both types of heart failure falls into four broad areas: lifestyle modifications, medication, nonsurgical interventions, and surgery.

Lifestyle modifications include a low-sodium diet and fluid restriction. Because one of the body's first lines of defense against heart failure is to decrease sodium and water excretion by the kidneys, reducing sodium and fluid consumption can ease heart failure symptoms and reduce the patient's need for diuretics.

Regular exercise can reduce heart failure symptoms and improve quality of life and exercise capacity. Eating a low-fat diet, losing weight, stopping smoking, and limiting alcohol intake can help keep the patient's blood pressure (BP) down and may prevent heart failure from developing in high-risk patients.

Drug therapy for heart failure is aimed at relieving signs and symptoms and slowing or reversing ventricular remodeling. Typically, the health care provider prescribes therapy from among these drug classes: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, loop diuretics, and digoxin.

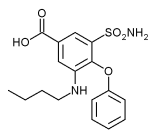

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, such as captopril and enalapril, block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, a vasoconstrictor that can raise BP. These drugs alleviate heart failure symptoms by causing vasodilation and decreasing myocardial workload. The most common adverse reaction to ACE inhibitors is a dry cough. Other adverse reactions include hypotension, worsening renal function, and potassium retention. Patients who can't take ACE inhibitors may be prescribed angiotensin receptor blockers instead.

Beta-adrenergic blockers, such as bisoprolol, metoprolol, and carvedilol, reduce heart rate, peripheral vasoconstriction, and myocardial ischemia. Long-term therapy reduces heart failure symptoms and improves the patient's functional status.

Diuretics prompt the kidneys to excrete sodium, chloride, and water, reducing fluid volume. Loop diuretics such as furosemide, bumetanide, and torsemide are the preferred first-line diuretics because of their efficacy in patients with and without renal impairment. Low-dose spironolactone may be added to a patient's regimen if he has recent or recurrent symptoms at rest despite therapy with ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, digoxin, and diuretics. Diuretics should never be used alone to treat heart failure because they don't prevent further myocardial damage.

Aldosterone receptor antagonists such as eplerenone block aldosterone from binding to receptors in the kidneys. This lets the kidneys get rid of excess sodium and water.

Digoxin increases the heart's ability to contract and improves heart failure symptoms and exercise tolerance in patients with mild to moderate heart failure. Major adverse reactions include arrhythmias, gastrointestinal problems such as anorexia, and neurologic symptoms such as confusion.

Other drug options include nesiritide (Natrecor), a preparation of human BNP that mimics the action of endogenous BNP, causing diuresis and vasodilation, reducing BP, and improving cardiac output.

Intravenous (I.V.) positive inotropes such as dobutamine, dopamine, and milrinone, as well as vasodilators such as nitroglycerin or nitroprusside, are used for patients who continue to have heart failure symptoms despite oral medications. Although these drugs act in different ways, all are given to try to improve cardiac function and promote diuresis and clinical stability. Intravenous positive inotropes also can be used for long-term support-for example, for patients awaiting cardiac transplant-via a tunneled central venous catheter or peripherally inserted central catheter.

Exploring nonsurgical options

Among the nonsurgical options for treating heart failure are enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) and biventricular pacing, also called cardiac resynchronization therapy.

In EECP, which is noninvasive, three sets of pneumatic cuffs are wrapped around the patient's calves, thighs, and buttocks and inflated in synchrony with the patient's ECG. The cuffs inflate during diastole (increasing venous return to the heart) and deflate during systole (decreasing after-load and reducing ischemia and myocardial workload). This therapy can't be used in patients with decompensated heart failure, severe aortic insufficiency, severe peripheral arterial disease, or severe hypertension.

Patients undergoing EECP are at risk for skin breakdown from the cuffs and back and muscle pain from immobility during therapy. Increased venous return to the right side of the heart also increases the risk of unstable angina, arrhythmias, or exacerbation of heart failure.

The biventricular pacer resynchronizes ventricular contractions, improving left ventricular filling and cardiac output. The device, which uses leads placed in each ventricle and in the right atrium, is an option for patients whose heart failure symptoms haven't responded well to drug therapy. Because the pacemaker is implanted, infection is the most common risk of this intervention.

Turning to surgery

Heart transplant is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage heart failure (defined as severe functional impairment, dependence on I.V. inotropic medications, recurrent life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, or angina refractory to all available treatments). But the demand for donor hearts far exceeds the supply, and some patients aren't candidates for transplantation. For this reason, surgically implanted devices have been developed to help restore functional abilities to some patients with severe heart failure:

* Ventricular assist devices (VADs) are mechanical pumps that take over the function of a failing ventricle. Indicated for patients whose heart failure is refractory to medical management, VADs can serve as a long-term mechanical support or as a bridge to transplant.

* The Myosplint device aims to pull the diseased heart into a more normal shape, improving heart failure symptoms. The Myosplint consists of flexible cords that the surgeon places inside the left ventricle and tightens to reduce the ventricle's size.

* The CorCap cardiac support device by Acorn Cardiovascular, Inc., is a mesh fabric jacket that's wrapped around the ventricles to provide myocardial support and reduce wall stress. This device is available in Europe but still under investigation in the United States. Early studies have shown that this device improves cardiac function by making the ventricle's shape more physiologically correct and stopping further ventricular remodeling.

What your patient needs to know

Teaching your patient about the progression and treatment of his disease is key to helping him identify changes in his condition so he can seek medical treatment before acute decompensation occurs. Explain the symptoms he should watch for, such as sudden, unexplained weight gain, and when to call his health care provider. Teach him about his medications and dietary sodium restriction and tell him to weigh himself daily. Refer him to support groups. If he smokes, encourage him to stop.

By keeping up-to-date with heart failure treatment, you can help your patient stay comfortable, improve his quality of life, and minimize his hospital admissions.

SELECTED WEB SITE

Heart Failure Society of America

http://www.hfsa.org

Last accessed on August 11, 2004.

To take this test online, visit http://www.nursingcenter.com/ce/nursing.

CE Test

Managing heart failure: What you need to know

Instructions:

* Read the article beginning on page 4.

* Take the test, recording your answers in the test answers section (Section B) of the CE enrollment form. Each question has only one correct answer.

* Complete registration information (Section A) and course evaluation (Section C).

* Mail completed test with registration fee to: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, CE Group, 333 7th Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, NY 10001.

* Within 3 to 4 weeks after your CE enrollment form is received, you will be notified of your test results.

* If you pass, you will receive a certificate of earned contact hours and an answer key. If you fail, you have the option of taking the test again at no additional cost.

* A passing score for this test is 15 correct answers.

* Need CE STAT? Visit http://www.nursingcenter.com for immediate results, other CE activities, and your personalized CE planner tool.

* No Internet access? Call 1-800-933-6525 for other rush service options.

* Questions? Contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 646-674-6617 or 646-674-6621.

Registration Deadline: October 31, 2006

Provider Accreditation:

This Continuing Nursing Education (CNE) activity for 2.0 contact hours is provided by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, which is accredited as a provider of continuing education in nursing by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation and by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN 00012278, CERP Category A). This activity is also provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider Number CEP 11749 for 2.0 contact hours. LWW is also an approved provider of CNE in Alabama, Florida, and Iowa and holds the following provider numbers: AL #ABNP0114, FL #FBN2454, IA #75. All of its home study activities are classified for Texas nursing continuing education requirements as Type I.

Your certificate is valid in all states. This means that your certificate of earned contact hours is valid no matter where you live.

Payment and Discounts:

* The registration fee for this test is $13.95.

* If you take two or more tests in any nursing journal published by LWW and send in your CE enrollment forms together, you may deduct $0.75 from the price of each test.

* We offer special discounts for as few as six tests and institutional bulk discounts for multiple tests. Call 1-800-933-6525 for more information.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Bosen, D.: "New Strategies for Treating Patients with Heart Failure," Nursing2003. 33(12):44-47, December 2003.

Hunt, S., et al.: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). 2001, http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/failure/hf_index.htm.

Remme, W., et al. Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure, European Society of Cardiology: "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Heart Failure," European Heart Journal. 22(17):1527-1560, September 2001.

Rodgers, J., and Reeder, S.: "Current Therapies in the Management of Systolic and Diastolic Dysfunction," Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 20(6):2-13, November/December 2001.

By Dawn M. Christensen

RN, ACNP, FNP, MS

Dawn M. Christensen is circulatory support coordinator at Penn State's Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa.

The author has disclosed that she has no significant relationship with or financial interest in any commercial companies that pertain to this educational activity.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Fall 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved