Key words: Buprenorphine; Cocaine; Addiction

INTRODUCTION

Cocaine use in combination with heroin ("speedballing") and with methadone are widespread clinical problems (1, 2). These problems may reflect some reinforcing interaction between mu opioid agonists and cocaine. Acute coadministration of the pure opiate agonist morphine with cocaine has been shown to enhance cocaine's effects (3).

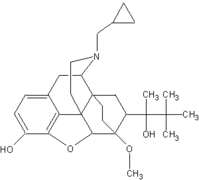

The mixed opioid agonist-antagonist buprenorphine is being evaluated for treatment of opioid addiction (4, 5). Unlike methadone, buprenorphine has shown minor cardiovascular effects across a wide range of doses (6), and buprenorphine's antagonist effects at higher doses make overdose difficult (7). Compared with the mu opioid agonist methadone, the withdrawal syndrome from buprenorphine is relatively mild (8, 9).

In a similar fashion to the mu opioid agonists, buprenorphine may also have a reinforcing interaction with cocaine. Low doses of sublingual buprenorphine given to nondependent subjects show opioid agonist effects (6). Acute buprenorphine appears to enhance cocaine's pleasurable effects in recent preclinical studies using different paradigms: conditioned place preference (10), discriminative stimulus (11), and self-administration (12). Thus, examination of potential buprenorphine cocaine interactions in humans is warranted.

This study was designed to determine whether coadministration of acute buprenorphine enhanced the subjective and cardiovascular effects of intranasal cocaine in humans using a double blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Patients were maintained on buprenorphine and placebo for 5 days each and received intranasal cocaine on Days 3 and 5 of each maintenance period. Days 3 and 5 were chosen to represent two time points before tolerance to buprenorphine had developed. In order to observe a maximal cocaine-buprenorphine interaction, cocaine challenges were 2 hours after the morning buprenorphine dose, at the time of the peak buprenorphine effect (13).

METHODS

Subjects

The five patients (three male, two female) were dually addicted to intravenous cocaine and heroin. They had a mean age of 32.6 years (range 20-40). All the patients had been actively abusing both opiates and cocaine immediately prior to enrollment in the study. Mean duration of intravenous opiate abuse was 12.9 (SD = 4.7) years. One patient had been maintained on buprenorphine for 6 months immediately prior to enrollment. The mean duration of cocaine abuse was 12.5 (SD = 5.1) years, most recently intravenously. Patients gave voluntary written informed consent for participation in the study, and were paid for completion.

Procedure

The patients were hospitalized on the Treatment Research Unit of the Connecticut Mental Health Center, where they were detoxified from opioids in 3 days with clonidine and naltrexone (14). After at least 36 hours free of any medication, patients self-administered a 2-mg per kg dose of intranasal cocaine in a specially monitored test room. The room had comfortable chairs and a radio. The purpose of this test dose was to familiarize the patients with the room and with challenge rating scales, as well as to monitor for medical safety. A nurse trained in advanced cardiac life support was in constant attendance. A physician was present during the cocaine administration.

The patients were then randomized to either buprenorphine or placebo. After 1 day on 1 mg sublingual buprenorphine, each patient was increased to 2 mg sublingual buprenorphine (Day 2) for Days 2 to 5. Intranasal cocaine (2 mg per kg) was self-administered on Days 3 and 5. After a 2-day washout the patient was crossed over to the opposite condition and cocaine challenges were repeated on Days 3 and 5 of that condition. Thus, the patients initially on buprenorphine were off buprenorphine for at least 5 days before the next cocaine dose on placebo treatment.

The patients did not eat or drink for 10 hours prior to cocaine challenge sessions. Buprenorphine was given at 7 A.M. on the morning of the test days, approximately 2 hours before the cocaine was given. After baseline cardiovascular and subjective ratings, the patients self-administered intranasal cocaine with a straw.

Rating Scales

On a visual analogue scale (VAS) with lines anchored from 0 to 100, patients rated current feelings of high, pleasant, and cocaine effect compared to usual street use ("0 = imperceptible," "50 = about the same as usual, "and "100 = better than the best"). The VAS, blood pressure, pulse, and respirations were taken at 2 minutes before and 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, and 240 minutes after the cocaine challenge dose. The first time point after self-administration of cocaine was at 15 minutes because cocaine peak effects are delayed after intranasal use (15). A 72-item version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) (16) was administered at time points -2, +15, +30, and +60 minutes. In addition to the eight symptom clusters defined by the original scale, we examined two derived scales. Arousal scores were obtained by subtracting the sum of the scores for Confusion and Fatigue from the sum of the scores for Vigor and Anxiety; and Positive Mood scores were obtained by subtracting the Depression from the Elation score. This version of the POMS has been shown to be sensitive to cocaine's effects (17).

Data Analysis

Four patients completed the test dose and four subsequent challenges. One patient, due to scheduling difficulties, only completed the test dose and two challenges--one each on Day 3 of buprenorphine and Day 3 of placebo.

The area under the curve (AUC) for all variables was determined for the time period -2 to + 60 minutes, as this time period represents the time of maximum intranasal cocaine effects. Peaks and difference scores (peak minus baseline) were calculated for each variable within a challenge. Challenge outcome data were analyzed by 2-factor repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors: medication (buprenorphine vs placebo) and duration on medication (3 vs 5 days). Because negative values for POMS variables yield inaccurate AUCs, we added a constant of .4 to each time point for anxiety, 4 to positive mood, and 8 to arousal. Values at -2 minutes were considered baseline. The one patient who only completed Day 3 challenges was included in the descriptive data and in the comparison of effects by medication, but not in comparisons by duration.

Three patients had the sequence with buprenorphine first and two patients had the opposite sequence. Upon visual inspection of the data, the medication effects were similar for both sequences.

RESULTS

Medication Effects for Subjective Variables (Tables 1 and 2)

The mean AUCs for the VAS "Pleasant" subjective effects of cocaine and the POMS "Vigor" and "Arousal" were significantly greater with concomitant buprenorphine administration. These effects were greater for each of the five patients. The peak cocaine effect was higher only for Arousal. All the unpleasant effects of cocaine (Anger, Depression, Anxiety) were numerically attenuated by buprenorphine, but none significantly.

[TABULAR DATA 1 OMITTED]

[TABULAR DATA 2 OMITTED]

Medication Effects for Cardiovascular Variables

Table 3 lists the mean AUCs for the cardiovascular variables by medication, with both durations combined. Pulse was significantly higher on buprenorphine. Table 4 illustrates that this difference in AUC was partially accounted for by higher baseline values on buprenorphine.

[TABULAR DATA 3 OMITTED]

[TABULAR DATA 4 OMITTED]

Duration Effects

Table 5 lists the mean AUCs for each of the medication and duration conditions. The buprenorphine effect on Pleasant [F(df 1,8) = 47.2, p < .0061 and Confusion [F(df 1,8) = 22.6, p < .021 for Day 5 was more pleasurable than for Day 3. High (p < .06) and Friendliness (p < .03) showed more pleasurable responses on Day 5 than on Day 3 in the placebo condition, and the opposite pattern on the buprenorphine condition. More Vigor (p < .08) and Friendliness (p < .03) were shown on Day 5 than on Day 3 for placebo, and these scales showed essentially no change between Days 3 and 5 for buprenorphine.

[TABULAR DATA 5 OMITTED]

Figure 1 shows the mean high over time (within a challenge) for the four combinations of medication and duration. On Day 3, the High is greater at all time points with buprenorphine than with placebo. On Day 5, the High is similar with buprenorphine and with placebo.

There were no effects of buprenorphine duration on the cardiovascular data.

DISCUSSION

In these five pilot patients, acute buprenorphine enhanced cocaine-induced pleasurable and cardiovascular effects when buprenorphine was given before tolerance to its effects had developed, e.g., on Day 3. However, buprenorphine's enhancement of cocaine's pleasurable effects appeared to diminish on Day 5 compared to Day 3.

Buprenorphine Effects

Increased cocaine-induced pleasurable effects on buprenorphine probably are not due to the addition of independent effects of buprenorphine to those of cocaine. Two hours after buprenorphine, prior to cocaine challenges, ratings of High were relatively low (8.3 [+ or -] -5.9). This 2-hour time point probably represents a peak buprenorphine effect (13). Therefore, the higher difference scores for several pleasurable ratings on buprenorphine probably represents an interaction between buprenorphine and cocaine effects. Buprenorphine's enhancement of the cocaine-induced increase in pulse also probably represents a heightening of cocaine's effects. An addition of the cardiovascular effects of cocaine and buprenorphine is less likely, as a placebo-controlled study found no cardiovascular effects of sublingual buprenorphine at 2 mg (13).

Duration Effects

In the placebo condition, the Day 5 challenges showed more pleasurable effects and fewer dysphoric cocaine effects than the Day 3 challenges. These findings may be consistent with an expectation effect. The patients appeared to be apprehensive about their first (Day 3) challenge on a new medication condition; on Day 5 they were more relaxed, possibly because they knew what to expect. The challenges on buprenorphine showed the opposite pattern, toward more pleasurable subjective effects on Day 3 than on Day 5. This effect appears to reflect differences in the response to a combination of buprenorphine and cocaine from Day 3 to Day 5. There may be tolerance to the pleasurable effects of the drug combination. Alternatively, the difference between Day 3 and Day 5 may be accounted for by differences in the response to buprenorphine alone. Patients reported more intoxicating effects from the 7 a.m. buprenorphine on Day 3 than on Day 5. This may be due to early physiological tolerance.

An attenuation of cocaine's euphorigenic effects on buprenorphine from Day 3 to Day 5 would be consistent with studies showing a different interaction between acute and chronic buprenorphine with cocaine. Acutely, buprenorphine pretreatment enhances cocaine-conditioned place preference (10), but chronic buprenorphine pretreatment attenuates it (18, 19). Chronic buprenorphine treatment has been shown to suppress cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys (20). Longer-term maintenance treatment was examined in a recent human intravenous cocaine challenge study (21), in which 2 weeks of sublingual buprenorphine treatment at 4 mg daily caused a slight reduction in ratings of cocaine's pleasant effects, without altering the cardiovascular response to cocaine. Clinical studies (22) suggested that cocaine use might decrease with buprenorphine treatment.

Study Design Issues

The use of intranasal cocaine and the lack of cocaine blood levels made it impossible to determine whether the effect we saw was pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic. The absorption of intranasal cocaine is somewhat variable, probably due to local vasoconstriction (23). It is theoretically possible that buprenorphine alters nasal vasodilation or peripheral metabolism of cocaine.

Intranasal cocaine produced a robust signal in our patients, as it has in other studies (24). The mean peak rating of the challenge cocaine, compared to what the patient expected from cocaine, was 48 [+ or -] 17 on a scale anchored by "0 = no effect," "50 = about the same as usual," and "100 = better than the best. Thus, the magnitude of our cocaine challenge dose approximated what our addicts used illicitly. Although it was not the preferred route of administration for our patients, all of our patients had used intranasal cocaine previously.

The dually addicted patients in this study were accustomed to using opiates and cocaine together. There may be a conditioned "high" in opiate addicts on buprenorphine (25) which is not present in opiate-naive patients.

Dosage Effects

We only studied a single dosage of cocaine and a single dosage of buprenorphine. The enhancement of cocaine's effects by buprenorphine might become dysphoric with higher doses of cocaine, e.g., a pleasant rush which is accentuated might cause panic. One patient reported that he always experienced a "panicky" feeling in his chest with cocaine, and that this was accentuated, but still not troublesome, on buprenorphine. In the study by Foltin and Fischman (3) of the effects of coadministered cocaine and morphine, the interactions depended on the dosages used.

Recently, clinical trials with low dose (i.e., 2 mg) buprenorphine maintenance suggested that this dose is ineffective for treatment of cocaine-abusing opiate addicts (5, 26). Given acutely to opiate-detoxified patients, 2 mg buprenorphine has mostly opiate agonist effects (13). At higher doses, which have more antagonist effects, buprenorphine may interact with cocaine differently. In a study of nonopiate-using patients (27), the mu receptor antagonist naltrexone attenuated the pleasant subjective effects of intravenous cocaine.

Our preliminary study suggests that acutely 2 mg sublingual buprenorphine accentuates intranasal cocaine's effects. Questions to be addressed in the future include whether cocaine interacts differently with buprenorphine than with methadone, effects of higher buprenorphine doses, and effects of longer-term buprenorphine treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Grants R18-DA06190 and K02-DA00112 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse to Dr. Kosten.

REFERENCES

(1.) Schnoll, S. H., Karrigan, J., Kitchen, S. B., Daghestani, A., and Hansen, T., Characteristics of cocaine abusers presenting for treatment, in Cocaine Use in America: Epidemiological and Clinical Perspectives (N. J. Kozel and E. H. Adams, Eds.), (National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 61), U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1985, pp. 171-181. (2.) Kosten, T. R., Rounsaville, B. J., and Kleber, H. D., A 2.5 year follow-up of cocaine use among treated opiate addicts, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 44:281-284 (1987). (3.) Foltin, R. W., and Fischman, M. W., Cardiovascular and subjective effects of intravenous cocain and morphine combinations ("speedballs") in humans, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 261(2):623-632 (1992). (4.) Rosen, M. I., and Kosten, T. R., Buprenorphine: Beyond methadone, Hosp. Commun. Psychiatry 42:347-349 (1991). (5.) Johnson, R. E., Jaffe, J. H., and Fudala, P. J., A controlled trial of buprenorphine treatment for opiate dependence, JAMA 267(20):2750-2755 (1992). (6.) Walsh, S. T., Preston, M. D., Stitzer, S. T., Dickerson, S. L., Cone, E. J., and Bigelow, G. E., The behavioral and pharmacokinetic profile of high dose buprenorphine administered sublingually in humans, Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. (1991). (7.) Lewis, J. W., Buprenorphine, Drug Alcohol Depend. 14:363-372 (1985). (8.) Jasinski, D. R., Hevnick, J. S., and Griffith, J. D., Human pharmacology and abuse potential of the analgesic buprenorphine, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 35:601-616 (1978). (9.) Fudala, P. J., Jaffe, J. H., and Dax, E. M., Use of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction. II. Physiologic and behavioral effects of daily and alternate day administration and abrupt withdrawal, Clin. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 47:525-534 (1990). (10.) Brown, E. E., Finlay, J. M., Wong, J. T., Daamsa, G., and Fibiger, H. C., Behavioral and neurochemical interactions between cocaine and buprenorphine: Implications for the pharmacotherapy of cocaine abuse, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 256:119-126 (1991). (11.) Kamien, J. B., arid Spealman, R. D., Modulation of the discriminative-stimulus effects of coca by buprenorphine, Behav. Pharmacol. 2:517-520 (1991). (12.) Pettit, H. O., Smith, S., Eckstron, A. J., and Pryor, G. T., Evaluation of the effects of bupr in both a cocaine self-administration and drug-discrimination paradigm, Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. (1991). (13.) Jasinski, D. R., Fudala, P. J., and Johnson, R. E., Sublingual versus subcutaneous buprenorphi in opiate abusers, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 45:513-519 (1989). (14.) Vining, E., Kosten, T. R., and Kleber, H. D., Clinical utility of rapid clonidine-naltrexone detoxification for opioid abusers, Br. J. Addict. 83:567-575 (1988). (15.) Van Dyke, C., Jatlow, P., Barash, P. G., and Byck, R., Intranasal cocaine: Dose relationships of psychological effects and plasma levels, Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 12(1):1-13 (1982). (16.) McNair, D., Lorr , M., and Droppleman, L. F., Profile of Mood States, Educational and Industri Testing, San Diego, 1971. (17.) Fischman, M. W., Foltin, R. W., Nestadt, G., and Pearlson, G. D., Effects of desipramine maintenance on cocaine self-administration by humans, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 253:760-770 (1990). (18.) Kosten, T. A., Marby, D. W., and Nestler, E. J., Cocaine conditioned place preference is atten by chronic buprenorphine treatment, Life Sci. 49:201-207 (1991a). (19.) Suzuki, T., Shiozaki, Y., Masukawa, Y., Misawa, M., and Nagasc, H., The role of mu and kappa-opioid receptors in cocaine-induced conditioned place preference, Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 58:435-442 (1992). (20.) Mello, N. K., Lukas, S. E., Kamien, J. B., Mendelson, J. H., Drieze, J., and Cone, E. J., The effects of chronic buprenorphrine treatment on cocaine and food self-administration by rhesus monkeys, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 260(3):1185-1193 (1992). (21.) Teoh, S. K., Sintavanarong, P., Kuehnle, J., Mendelson, J. H., Hallgring, E., Rhoades, E., and Mello, N. K., Buprenorphine effects on morphine and cocaine challenges in heroin and cocaine dependent men, in Proceedings of the Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence 1991 (L. S. Harris, Ed.), National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, Maryland, In Press. (22.) Kosten, T. R., Kleber, H. D., and Morgan, C., Treatment of cocaine abuse with buprenorphine, Biol. Psychiatry 26:637-639 (1989). (23.) Wilkerson, P., Van Dyke, C., Jatlow, P., Barash, P., and Byck, R., Intranasal and oral cocaine kinetics, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 27(3):386-394 (1980). (24.) Van Dyke, C., Jatlow, P., Barash, P. G., and Byck, R., Oral cocaine: Plasma concentrations and central effects, Science 200(14):211-213 (1978). (25.) Cascella, N., Muntaner, C., Kumor, K. M., Nagoshi, C. T., Jaffe, J. H., and Sherer, M. A., Cardiovascular responses to cocaine placebo in humans: A preliminary report, Biol. Psychiatry 25:285-295 (1989). (26.) Kosten, T. R., Schottenfeld, R. S., Morgan, C. H., Falcioni, J., and Ziedonis, D., Buprenorphi vs methadone for opioid and cocaine dependence, in Proceedings of the Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence 1991 (L. S. Harris, Ed.), National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, Maryland, In Press. (27.) Kosten, T. R., Silverman, D. G., Fleming, J., Kosten, T. A., Gavin, F. H., Compton, N., Jatlow, P., and Byck, R., Intravenous cocaine challenges during naltrexone maintenance, Biol. Psychiary, In Press.

Marc I. Rosen,(*) M.D. (*) To whom correspondence should be addressed at Connecticut Mental Health Center, 34 Park Street, New Haven, Connecticut 06508. Telephone: (202) 789-7205.

COPYRIGHT 1993 Taylor & Francis Ltd.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group