**********

Hyponatremia generally is defined as a plasma sodium level of less than 135 mEq per L (135 mmol per L). (1,2) This electrolyte imbalance is encountered commonly in hospital and ambulatory settings. (3) The results of one prevalence study (4) in a nursing home population demonstrated that 18 percent of the residents were in a hyponatremic state, and 53 percent had experienced at least one episode of hyponatremia in the previous 12 months. Acute or symptomatic hyponatremia can lead to significant rates of morbidity and mortality. (5-7) Mortality rates as high as 17.9 percent have been quoted, but rates this extreme usually occur in the context of hospitalized patients. (8) Morbidity also can result from rapid correction of hyponatremia. (9,10) Because there are many causes of hyponatremia and the treatment differs according to the cause, a logical and efficient approach to the evaluation and management of patients with hyponatremia is imperative.

Water and Sodium Balance

Plasma osmolality, a major determinant of total body water homeostasis, is measured by the number of solute particles present in 1 kg of plasma. It is calculated in mmol per L by using this formula:

2 - [sodium] + [urea] + [glucose]

Total body sodium is primarily extracellular, and any increase results in increased tonicity, which stimulates the thirst center and arginine vasopressin secretion. Arginine vasopressin then acts on the V2 receptors in the renal tubules, causing increased water reabsorption. The opposite occurs with decreased extracellular sodium: a decrease inhibits the thirst center and arginine vasopressin secretion, resulting in diuresis. In most cases, hyponatremia results when the elimination of total body water decreases. The pathophysiology of hyponatremia will be discussed later in this article.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Most patients with hyponatremia are asymptomatic. Symptoms do not usually appear until the plasma sodium level drops below 120 mEq per L (120 mmol per L) and usually are nonspecific (e.g., headache, lethargy, nausea). (11) In cases of severe hyponatremia, neurologic and gastrointestinal symptoms predominate. (3) The risk of seizures and coma increases as the sodium level decreases. The development of clinical signs and symptoms also depends on the rapidity with which the plasma sodium level decreases. In the event of a rapid decrease, the patient can be symptomatic even with a plasma sodium level above 120 mEq per L. Poor prognostic factors for severe hyponatremia in hospitalized patients include the presence of symptoms, sepsis, and respiratory failure. (12)

Diagnostic Strategy

Figure 1 (13) shows an algorithm for the assessment of hyponatremia. The identification of hyponatremia must be followed by a clinical assessment of the patient, beginning with a targeted history to elicit the symptoms of hyponatremia and exclude important causes such as congestive heart failure, liver or renal impairment, malignancy, hypothyroidism, Addison's disease, gastrointestinal losses, psychiatric illness, recent drug ingestion, surgery, or reception of intravenous fluids. The patient then should be classified into one of the following categories: hypervolemic (edematous), hypovolemic (volume depleted), or euvolemic.

HYPERVOLEMIC HYPONATREMIA

Hyponatremia in the presence of edema indicates increased total body sodium and water. This increase in total body water is greater than the total body sodium level, resulting in edema. The three main causes of hypervolemic hyponatremia are congestive heart failure, liver cirrhosis, and renal diseases such as renal failure and nephrotic syndrome. These disorders usually are obvious from the clinical history and physical examination alone.

EUVOLEMIC AND HYPOVOLEMIC HYPONATREMIA

Hyponatremia in a volume-depleted patient is caused by a deficit in total body sodium and total body water, with a disproportionately greater sodium loss, whereas in euvolemic hyponatremia, the total body sodium level is normal or near normal. Differentiating between hypovolemia and euvolemia may be clinically difficult, especially if the classic features of volume depletion such as postural hypotension and tachycardia are absent. (14)

Laboratory markers of hypovolemia, such as a raised hematocrit level and blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine ratio of more than 20, may not be present. In fact, results of one study (15) showed an increased BUN-tocreatinine ratio in only 68 percent of hypovolemic patients. Two useful aids for evaluating euvolemic or hypovolemic patients are measurement of plasma osmolality and urinary sodium concentration. Plasma osmolality testing places the patient into one of three categories, normal, high, or low plasma osmolality, while urinary sodium concentration testing is used to refine the diagnosis in patients who have a low plasma osmolality.

Plasma Osmolality Measurement

NORMAL PLASMA OSMOLALITY

The combination of hyponatremia and normal plasma osmolality (280 to 300 mOsm per kg [280 to 300 mmol per kg]) of water can be caused by pseudohyponatremia or by the posttransurethral prostatic resection syndrome. The phenomenon of pseudohyponatremia is explained by the increased percentage of large molecular particles, such as proteins and fats in the serum, relative to sodium. These large molecules do not contribute to plasma osmolality, resulting in a state in which the relative sodium concentration is decreased, but the overall osmolality remains unchanged. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and hyperproteinemia are two causes of this condition in patients with pseudohyponatremia. These patients usually are euvolemic.

The post-transurethral prostatic resection syndrome consists of hyponatremia with possible neurologic deficits and cardiorespiratory compromise. Although the syndrome has been attributed to the absorption of large volumes of hypotonic irrigation fluid intraoperatively, its pathophysiology and management remain controversial. (16)

INCREASED PLASMA OSMOLALITY

Increased plasma osmolality (more than 300 mOsm per kg of water) in a patient with hyponatremia is caused by severe hyperglycemia, such as that occurring with diabetic ketoacidosis or a hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. It is caused by the presence of glucose molecules that exert an osmotic force and draw water from the intracellular compartment into the plasma, with a diluting effect. Osmotic diuresis from glucose then results in hypovolemia. Fortunately, hyperglycemia can be diagnosed easily by measuring the bedside capillary blood glucose level.

DECREASED PLASMA OSMOLALITY

Patients with low plasma osmolality (less than 280 mOsm per kg of water) can be hypovolemic or euvolemic. The level of urine sodium is used to further refine the differential diagnosis.

High Urine Sodium Level. Excess renal sodium loss can be confirmed by finding a high urinary sodium concentration (more than 30 mmol per L). In these patients, the main causes of hyponatremia are renal disorders, endocrine deficiencies, reset osmostat syndrome, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and drugs or medications. Because of their prevalence and importance, SIADH and drugs deserve special mention, and the author will elaborate on these causes later in the article.

Renal disorders that cause hyponatremia include sodium-losing nephropathy from chronic renal disease (e.g., polycystic kidney, chronic pyelonephritis) and the hyponatremic hypertensive syndrome that frequently occurs in patients with renal ischemia (e.g., renal artery stenosis or occlusion). (17) The combinations of hypertension plus hypokalemia (renal artery stenosis) or hyperkalemia (renal failure) are useful clues to this syndrome.

Endocrine disorders are uncommon causes of hyponatremia. Diagnosing hypothyroidism or mineralocorticoid deficiency (i.e., Addison's disease) as a cause of hyponatremia requires a high index of suspicion, because the clinical signs can be quite subtle. In either case, the serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) should be measured, because hypothyroidism and hypoadrenalism can coexist as a polyendocrine deficiency disorder (i.e., Schmidt's syndrome). Treatment of Schmidt's syndrome involves steroid replacement before thyroxine [T.sub.4] therapy to avoid precipitating an addisonian crisis.

The reset osmostat syndrome occurs when the threshold for antidiuretic hormone secretion is reset downward. Patients with this condition have normal water-load excretion and intact urine-diluting ability after an oral water-loading test. The condition is chronic--but stable--hyponatremia. (18) It can be caused by pregnancy, quadriplegia, malignancy, malnutrition, or any chronic debilitating disease.

Low Urine Sodium Level. Patients with extra-renal sodium loss have a low urinary sodium concentration (less than 30 mmol per L) as the body attempts to conserve sodium. Causes include severe burns and gastrointestinal losses from vomiting or diarrhea. Acute water overload, which usually is obvious from the patient's history, occurs in patients who have been hydrated rapidly with hypotonic fluids, as well as in psychiatric patients with psychogenic overdrinking.

Diuretic therapy, on the other hand, can cause either a low or a high urinary-sodium concentration, depending on the timing of the last diuretic dose administered, but the presence of concomitant hypokalemia is an important clue to the use of a diuretic. (19)

Drug and Medication Use

Medications and drugs that cause hyponatremia are listed in Table 1. (20-26) Some of the more common causes of medication-induced hyponatremia are diuretics (20) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). (27) Most of the medications cause SIADH, resulting in euvolemic hyponatremia. Diuretics cause a hypovolemic hyponatremia. Fortunately, in most cases, stopping the offending agent is sufficient to cause spontaneous resolution of the electrolyte imbalance.

SIADH

SIADH is an important cause of hyponatremia that occurs when normal bodily control of antidiuretic hormone secretion is lost and antidiuretic hormone is secreted independently of the body's need to conserve water. Antidiuretic hormone causes water retention, so hyponatremia then occurs as a result of inappropriately increased water retention in the presence of sodium loss. The diagnostic criteria for SIADH are listed in Table 2. (28)

SIADH is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected when hyponatremia is accompanied by urine that is hyperosmolar compared with the plasma. This situation implies the presence of a low plasma osmolality with an inappropriately high urine osmolality, although the urine osmolality does not necessarily have to exceed the normal range. Another suggestive feature is the presence of hypouricemia caused by increased fractional excretion of urate. (29) Common causes of SIADH are listed in Table 3.

Any cerebral insult, from tumors to infections, can cause SIADH. Pneumonia and empyema are well-known pulmonary causes, with legionnaires' disease being a classic example. (30) Another pulmonary cause is bronchogenic carcinoma and, in particular, smallcell carcinoma, which is also the most common cause of ectopic antidiuretic hormone secretion. (31) Drug-induced SIADH is relatively common. Less common causes include acute intermittent porphyria, multiple sclerosis, and Guillain-Barre syndrome.

Treatment

The treatment of hyponatremia can be divided into two steps. First, the physician must decide whether immediate treatment is required. This decision is based on the presence of symptoms, the degree of hyponatremia, whether the condition is acute (arbitrarily defined as a duration of less than 48 hours) or chronic, and the presence of any degree of hypotension. The second step is to determine the most appropriate method of correcting the hyponatremia. Shock resulting from volume depletion should be treated with intravenous isotonic saline.

Acute severe hyponatremia (i.e., less than 125 mmol per L) usually is associated with neurologic symptoms such as seizures and should be treated urgently because of the high risk of cerebral edema and hyponatremic encephalopathy. (32) The initial correction rate with hypertonic saline should not exceed 1 to 2 mmol per L per hour, and normo/hypernatremia should be avoided in the first 48 hours. (33-35)

In patients with chronic hyponatremia, overzealous and rapid correction should be avoided because it can lead to central pontine myelinolysis. (9,10) In central pontine myelinolysis, neurologic symptoms usually occur one to six days after correction and often are irreversible. (19) In most cases of chronic asymptomatic hyponatremia, removing the

underlying cause of the hyponatremia suffices. (9) Otherwise, fluid restriction (less than 1 to 1.5 L per day) is the mainstay of treatment and the preferred mode of treatment for mild to moderate SIADH. (20) The combination of loop diuretics with a high-sodium diet may be required to achieve an adequate response in patients with chronic SIADH.

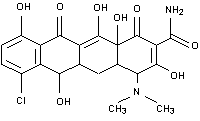

In patients who have difficulty adhering to fluid restriction or who have persistent severe hyponatremia despite the above measures, demeclocycline (Declomycin) in a dosage of 600 to 1,200 mg daily can be used to induce a negative free-water balance by causing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. (19,36) This medication should be used with caution in patients with hepatic or renal insufficiency. (37)

In patients with hypervolemic hyponatremia, fluid and sodium restriction is the preferred treatment. Loop diuretics can be used in severe cases. (38) Hemodialysis is an alternative in patients with renal impairment.

Newer agents such as the arginine vasopressin receptor antagonists have shown promising results (39) and may be useful in patients with chronic hyponatremia. (40)

In all patients with hyponatremia, the cause should be identified and treated. Some causes, such as congestive heart failure or use of diuretics, are obvious. Other causes, such as SIADH and endocrine deficiencies, usually require further evaluation before identification and appropriate treatment.

The author thanks Evelyn Koay, S.C., associate professor in the Department of Pathology, National University of Singapore, and director of the Molecular Diagnosis Center, National University Hospital, Singapore, for review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

(1.) DeVita MV, Gardenswartz MH, Konecky A, Zabetakis PM. Incidence and etiology of hyponatremia in an intensive care unit. Clin Nephrol 1990;34:163-6.

(2.) Kleinfeld M, Casimir M, Borra S. Hyponatremia as observed in a chronic disease facility. J Am Geriatr Soc 1979;27:156-61.

(3.) Kumar S, Berl T. Sodium. Lancet 1998;352:220-8.

(4.) Miller M, Morley JE, Rubenstein LZ. Hyponatremia in a nursing home population. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:1410-3.

(5.) Arieff AI. Hyponatremia, convulsions, respiratory arrest, and permanent brain damage after elective surgery in healthy women. N Engl J Med 1986; 314:1529-35.

(6.) Arieff AI, Ayus JC, Fraser CL. Hyponatraemia and death or permanent brain damage in healthy children. BMJ 1992;304:1218-22.

(7.) Ayus JC, Wheeler JM, Arieff AI. Postoperative hyponatremic encephalopathy in menstruant women. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:891-7.

(8.) Lee CT, Guo HR, Chen JB. Hyponatremia in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2000; 18:264-8.

(9.) Sterns RH, Cappuccio JD, Silver SM, Cohen EP. Neurologic sequelae after treatment of severe hyponatremia: a multicenter perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol 1994;4:1522-30.

(10.) Sterns RH, Riggs JE, Schochet SS Jr. Osmotic demyelination syndrome following correction of hyponatremia. N Engl J Med 1986;314:1535-42.

(11.) Walmsley RN, Watkinson LR, Koay ES. Cases in chemical pathology: a diagnostic approach. 3d ed. Singapore: World Scientific, 1992:22.

(12.) Nzerue CM, Baffoe-Bonnie H, You W, Falana B, Dai S. Predictors of outcome in hospitalized patients with severe hyponatremia. J Natl Med Assoc 2003; 95:335-43.

(13.) Koay ES, Walmsley RN. A primer of chemical pathology. Singapore: World Scientific, 1996:20.

(14.) McGee S, Abernethy WB 3d, Simel DL. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient hypovolemic? JAMA 1999;281:1022-9.

(15.) Thomas DR, Tariq SH, Makhdomm S, Haddad R, Moinuddin A. Physician misdiagnosis of dehydration in older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2003;4:251-4.

(16.) Agarwal R, Emmett M. The post-transurethral resection of prostate syndrome: therapeutic proposals. Am J Kidney Dis 1994;24:108-11.

(17.) Agarwal M, Lynn KL, Richards AM, Nicholls MG. Hyponatremic-hypertensive syndrome with renal ischemia: an underrecognized disorder. Hypertension 1999;33:1020-4.

(18.) Milionis HJ, Liamis GL, Elisaf MS. The hyponatremic patient: a systematic approach to laboratory diagnosis. CMAJ 2002;166:1056-62.

(19.) Janicic N, Verbalis JG. Evaluation and management of hypo-osmolality in hospitalized patients. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2003;32:459-81.

(20.) Spital A. Diuretic-induced hyponatremia. Am J Nephrol 1999;19:447-52.

(21.) Chan TY. Drug-induced syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Causes, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging 1997;11:27-44.

(22.) Chapman MD, Hanrahan R, McEwen J, Marley JE. Hyponatraemia and hypokalaemia due to indapamide. Med J Aust 2002;176:219-21.

(23.) Wilkinson TJ, Begg EJ, Winter AC, Sainsbury R. Incidence and risk factors for hyponatraemia following treatment with fluoxetine or paroxetine in elderly people. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999;47:211-7.

(24.) Liberopoulos EN, Alexandridis GH, Christidis DS, Elisaf MS. SIADH and hyponatremia with theophylline. Ann Pharmacother 2002;36:1180-2.

(25.) Patel GP, Kasiar JB. Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone-induced hyponatremia associated with amiodarone. Pharmacotherapy 2002; 22:649-51.

(26.) Hartung TK, Schofield E, Short AI, Parr MJ, Henry JA. Hyponatraemic states following 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, 'ecstasy') ingestion. QJM 2002;95:431-7.

(27.) Woo MH, Smythe MA. Association of SIADH with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother 1997;31:108-10.

(28.) Smith AF, Beckett GJ, Walker SW, Rae PW. Lecture notes on clinical biochemistry. 6th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1998:22.

(29.) Beck LH. Hypouricemia in the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. N Engl J Med 1979;301:528-30.

(30.) Fernandez JA, Lopez P, Orozco D, Merino J. Clinical study of an outbreak of Legionnaire's disease in Alcoy, Southeastern Spain. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2002;21:729-35.

(31.) Johnson BE, Damodaran A, Rushin J, Gross A, Le PT, Chen HC, et al. Ectopic production and processing of atrial natriuretic peptide in a small cell lung carcinoma cell line and tumor from a patient with hyponatremia. Cancer 1997;79:35-44.

(32.) Arieff AI, Llach F, Massry SG. Neurological manifestations and morbidity of hyponatremia: correlation with brain water and electrolytes. Medicine [Baltimore] 1976;55:121-9.

(33.) Ayus JC, Krothapalli RK, Arieff AI. Treatment of symptomatic hyponatremia and its relation to brain damage. A prospective study. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1190-5.

(34.) Gross P. Treatment of severe hyponatremia. Kidney Int 2001;60:2417-27.

(35.) Lauriat SM, Berl T. The hyponatremic patient: practical focus on therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997;8: 1599-607.

(36.) Forrest JN Jr, Cox M, Hong C, Morrison G, Bia M, Singer I. Superiority of demeclocycline over lithium in the treatment of chronic syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. N Engl J Med 1978;298:173-7.

(37.) Curtis NJ, van Heyningen C, Turner JJ. Irreversible nephrotoxicity from demeclocycline in the treatment of hyponatremia. Age Ageing 2002;31: 151-2.

(38.) Szatalowicz VL, Miller PD, Lacher JW, Gordon JA, Schrier RW. Comparative effect of diuretics on renal water excretion in hyponatremic oedematous disorders. Clin Sci [Lond] 1982;62:235-8.

(39.) Saito T, Ishikawa S, Abe K, Kamoi K, Yamada K, Shimizu K, et al. Acute aquaresis by the nonpeptide arginine vasopressin (AVP) antagonist OPC-31260 improves hyponatremia in patients with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82:1054-7.

(40.) Wong LL, Verbalis JG. Vasopressin V2 receptor antagonists. Cardiovasc Res 2001;51:391-402.

KIAN PENG GOH, M.R.C.P., is a registrar in the Department of Medicine at Alexandra Hospital, Singapore. He graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at the National University of Singapore, where he later obtained a master's degree in family medicine and membership in the United Kingdom's Royal College of Physicians.

Address correspondence to Kian Peng Goh, M.R.C.P., Department of Medicine, Alexandra Hospital, 378 Alexandra Rd., 159964, Singapore. Reprints are not available from the author.

The author indicates that he does not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

COPYRIGHT 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group