We describe a case of donor-acquired small cell lung cancer after pulmonary transplantation for cystic fibrosis. The recipient was an ex-smoker with minimal smoking history and had been abstinent for 20 years. At the time of death, the donor chest radiographic finding was normal. The recipient had multiple posttransplant bronchoscopies and a normal CT scan result at 4 months after transplantation. The recipient presented 13 months after transplantation with metastatic disease. He did not respond to chemotherapy and died shortly thereafter. Molecular genetic techniques revealed that the primary tumor and metastases were different to recipient tissues, confirming the donor origin. (CHEST 2001; 120:1030-1031)

Key words: bronchial neoplasm; lung transplantation; postoperative complications

We describe a case of donor-acquired small cell lung cancer after pulmonary transplantation for cystic fibrosis. Donor-acquired small cell lung carcinoma has never been described as a consequence of pulmonary transplantation, reflecting the carrel examination and selection of potential donor tissue, prior to grafting, by transplant surgeons.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year old man underwent bilateral lung transplantation for end-stage cystic fibrosis. His donor was a 50-year-old man, an ex-smoker with a 10-pack-year history who had abstained for 20 years prior to suffering a catastrophic subarachnoid hemorrhage. The recipient's posttransplant progress was straightforward, although a Pseudomonas empyema required drainage and IV antibiotics. Immunosuppression was conventional, with cyclosporine, azathioprine, and steroids following a 3-day course of induction antithymocyte globulin, as is routine at our center. Results of a CT scan of his chest performed at 4 months in order to investigate retrosternal pain were unremarkable. Surveillance bronchoscopy and transbronchial biopsy were carried out at 1 week, 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months. There was never any evidence of rejection on these biopsies (International Society for Heart-Lung Transplantation grade A1 or less), and no other endobronchial or histologic abnormalities were seen.

The patient presented 13 months after transplant with severe back pain after no obvious injury. Physical examination revealed local tenderness over the lumbosacral spine and right sacroiliac joint but no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Neurologic examination findings of the lower limbs were normal, as was sphincter control.

Investigations

Routine biochemistry revealed hyponatremia of 130 mmol/L with a grossly elevated alkaline phosphatase (1,212 IU/L; normal range, 35 to 115 IU/L). Bilirubin and alaninine transaminase levels were normal. Total and ionized calcium levels were raised. Results of thyroid function tests and prostate specific antigen were normal. C-reactive protein was elevated at 304 mg/L (normal range, 0 to 4 mg/L). Serum immunoelectrophoresis detected no paraproteins, and no Bence-Jones proteins were detected in the urine. The whole-blood cyclosporine level on hospital admission was 232 ng/mL.

Plain radiography confirmed a sclerotic lesion of the right scapula and also of the right sacral alae. Radioisotope bone scanning revealed numerous "hot spots" consistent with metastatic disease. CT of the abdomen revealed intrahepatic masses, and a CT-guided liver biopsy was performed. Histology revealed metastatic small cell carcinoma.

Progress

The patient was fully informed of his diagnosis. His cyclosporine dose was reduced to attain a level of 100 to 150 ng/mL. Demeclocycline was used to control hyponatremia. Rescue analgesia was commenced IV with ketamine and morphine and converted to oral when satisfactory analgesia was obtained. A modified regimen of carboplatin and oral etoposide was given as previously described.[1] Carboplatin was given as a single dose, 192 mg (adjusted to glomerular filtration rate), with a 3-day course of oral etoposide, 50 mg bid. Local radiotherapy was administered to the lumbar spine after the development of signs consistent with progressive disease. Pamidronate, 60 mg, was administered IV for metastatic bone pain.

There was no clinical response to chemotherapy, and the patient died 1 month after hospital admission. Consent was obtained for a postmortem examination; there were multiple liver and bone metastases together with a single small nodule in the allografted right lung. The esophagus was macroscopically normal.

Genetic Analysis

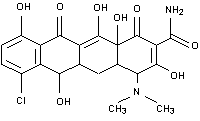

It was not possible to discern if the tumor was of donor or recipient origin using conventional techniques, as both the donor and recipient were men. Genetic analysis of the postmortem specimens of normal lung tissue, the lung primary, normal liver, and affected liver tissue was therefore carried out. Molecular genetic analysis was carried out on extracted DNA from donor lung tissue and recipient liver and heart using two randomly selected molecular probes, F13A01 and TH01. We used these probes to test if there were different allelic patterns between the tumor/metastases and nonaffected recipient tissue. If the patterns were different, then this would confirm the tumor was of donor origin. Affected liver was defined as liver tissue that appeared to have frank metastasis, while nonaffected had no evidence of macroscopic metastatic disease. Distinct and differing alleles were seen between affected liver/primary lung tumor and nonaffected heart/liver. The allelic pattern confirmed that the affected liver and primary lung tumor were syngeneic and distinct from the recipient heart and nonaffected liver, thus confirming that the tumor was of donor origin (Fig 1). A mixed allelic pattern of both donor and recipient appeared in the nonaffected lung, which we propose was secondary to a genetic admixture of recipient monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages and donor pneumocytes.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

DISCUSSION

Donor-acquired small cell lung carcinoma has never been described as a consequence of pulmonary transplantation, reflecting the careful examination and selection of potential donor tissue, prior to grafting, by transplant surgeons. Findings of the donor chest radiograph did not suggest any pulmonary pathology, and results of a CT scan, performed for other reasons, at 4 months, were normal even in retrospect. The patient underwent regular chest radiography in the course of his follow-up, but the nodule in the right lung was only discovered with the CT scan that characterized his metastatic disease. Regular bronchoscopies failed to demonstrate the primary lesion. The progression of the tumor in this patient was rapid given the previous normal CT scan, and was at the extremes of that seen in patients with native small cell cancer. It is tempting to speculate the role of immunosuppressants in this, given their effect on tumor surveillance.

We have made efforts to contact transplant centers that used other donor organs and are unaware of any of complications arising in these recipients. This report raises an important issue: a chronic shortage of donors has resulted in a waiting-list mortality of approximately 50%. A case report has previously questioned the validity of using donors with documented primary intracranial neoplasms as potential donors. Failure to use these patients as donors would reduce donor numbers further.[2] There is now an increasing pressure on transplant centers and their waiting lists due to increasing numbers of both referrals and accepted indications for transplantation. It is therefore unlikely that potential donors with such minimal smoking history would be excluded despite our experience.

REFERENCES

[1] Skarlos DV, Samantas E, Kosmidis P, et al. Randomised comparison of etoposide-cisplatin vs. etoposide-carboplatin and irradiation in small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 1994; 5:601-607

[2] Frank S, Muller J, Bonk C, et al. Transplantation of glioblastoma multiforme through liver transplantation [letter]. Lancet 1998; 352:31

(*) From the Departments of Cardiopulmonary Transplantation (Drs. De Soyza, Dark, and Corris) and Pathology (Dr. Parums), Freeman Hospital, and Department of Molecular Genetics (Dr. Curtis), University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

Manuscript received November 21, 2000; revision accepted February 23, 2001.

Correspondence to: Anthony G. De Soyza, MRCP, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; e-mail: Anthony.De-Soyza@ncl.ac.uk

COPYRIGHT 2001 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group