Dextromethorphan, the active ingredient in many over-the-counter cough and cold remedies, is probably the most widely used: anticoughing ingredient in the world. More than 70 cough and cold and flu products containing dextromethorphan are listed in the 2000 Physicians' Desk Reference for Nonprescription Drugs and Dietary Supplements, including several Robitussin, Vicks, and Triaminic products.

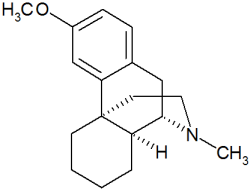

Dextromethorphan (DM) is an isomer of the codeine analogue levor- phanol and suppresses cough without the addictive properties of codeine and opioids. Up until about 3 years ago, DM was not perceived as a risky drug to take during pregnancy, although this perception was based on a small amount of human data. Some of this data came from the Boston Col- laborative Perinatal Project, which prospectively followed more than 50,000 mother-child pairs. The study did not detect an increase in major malformations among the babies of the 300 women who took DM during the first trimester of pregnancy.

But in 1998 the publication of a study that used a chick embryo model caused a great deal of havoc among teratologists, obstetricians, and others who care for pregnant women. The investigators exposed incubated chick embryos to DM during the time of neural tube closure and found evidence of neural crest and neural tube defects in the embryos that survived (Pediatr. Res. 43[1]:1-7, 1998). Extrapolating their results in a nonmammalian model to humans, they proposed that DM may have the same effects in humans.

In response, we began our own study, as did other investigators. In our prospective cohort study, we followed 184 mostly Canadian women who were counseled by the Motherisk Pro gram about the use of or exposure to a DM containing product during pregnancy. We compared them with a matched control group of pregnant women exposed to agents that do not pose a risk to the fetus. (The study was supported by five companies that market products that contain DM.)

Among the 128 women who took DM-containing products during the first trimester, there were three major malformations--for a 2.3% rate that was similar to the control group and within the expected rate of 1%-3%. Birth weights and the spontaneous abortion rate were also similar to controls and what would be expected in the general population (Chest 119[2]:466-69, 2001).

A series of 128 women is not large, so we conducted a metaanalysis of our data and all other data published up to this time. With the larger sample size we still found no evidence that the rate of major malformations was increased in babies exposed to DM in the first trimester.

In January, epidemiologists in Spain published the results of a retrospective, case-control study in which they asked mothers of children born with heart defects, neural tube defects, or other malformations and the mothers of children with no congenital defects if they had taken drugs containing DM or other drugs during pregnancy.

They found no excess of first-trimester DM use among the mothers of the children with congenital defects and concluded cough medicines containing DM do not increase the risk of these malformations (Teratology 63[1]:38-41, 2001).

While these studies cannot rule out a small risk for rare malformations, the results almost nullify the possibility that DM is a major teratogen.

This is important information because millions of women take products with DM before they know they are pregnant--almost half of all pregnancies are unintended.

Not every cough needs to be treated, but there are pregnant women who have severe coughs associated with conditions like pneumonia who do need treatment.

Because of this reassuring information and its proven efficacy, DM is considered by many to be the drug of choice for cough during pregnancy. Women who took DM-containing products before they knew they were pregnant can be reassured.

During, lactation, small amounts of DM enter the breast milk but don't have adverse effects on nursing babies. Moreover, there are approved infant cough and cold products that contain DM.

DR. GIDEON KOREN is professor of pediatrics, pharmacy, pharmacology, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto. He is also director of the Motherisk Program at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto,

COPYRIGHT 2001 International Medical News Group

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group