Abstract

Problem Need to improve the efficiency of postoperative pain management by early switching from intravenous to oral acetaminophen.

Design Implementation of local guidelines aimed at improving nurses' and doctors' behaviour. A controlled, prospective, before and after study evaluated its impact on appropriateness and costs.

Background and setting Orthopaedic surgery department (intervention) and all other surgical departments (control) of a university hospital. Five anaesthetists and 30 nurses of orthopaedic department participated in study.

Key measures for improvement Reducing number of acetaminophen injections per patient, reducing consumption of acetaminophen injections; cost savings over a one year period.

Strategies for improvement Multifaceted intervention included a local consensus process, short educational presentation, poster displayed in all nurses' offices, and feedback of practices six months after implementation of guidelines.

Effects of change Mean number of acetaminophen injections per patient decreased from 6.81 before intervention to 2.36 six months after. Monthly consumption of acetaminophen injections per 100 patients decreased by 320.9 (95% confidence interval 192.4 to 449.4) in intervention department and remained unchanged in control departments. Annual cost reduction was projected to be 15 100 [pounds sterling].

Lessons learnt Simple and locally implemented guidelines can improve practices and cut costs. Educational interventions can improve professionals' behaviour when they are based on actual working practices, use interactive techniques such as discussion groups, and are associated with other effective implementation strategies.

Introduction

At a time of diminishing healthcare resources, clinical guidelines are considered essential tools to reduce inappropriate use of drugs.[1] To overcome barriers to their adoption, clinical guidelines should be simple[2] and supported by active implementation strategies.[3-5] Because drugs are prescribed by doctors and administered by nurses, clinical guidelines should address both doctors' and nurses' behaviours. This is particularly important with regard to nurses' pivotal role in pain management. However, few published studies have evaluated the effectiveness of implementing guidelines that target nurses' behaviour.[6 7]

Our study was aimed at obtaining an early switch from the intravenous to the oral route of administration of acetaminophen in the management of acute pain after orthopaedic surgery. We conducted the study because the daily hospital acquisition cost of intravenous acetaminophen (propacetamol) and medical devices for infusion is 80 times higher than that for oral treatment, and because oral treatment (paracetamol) is at least as effective as propacetamol. We used a quasi-experimental design to assess the impact of a multifaceted intervention on doctors' and nurses' behaviour. Its results give some insights for the local introduction of guidelines targeting both nurses and doctors.

Background

Outline of problem

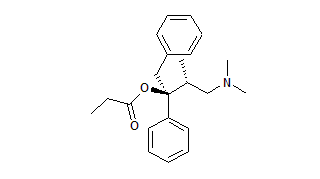

Propacetamol (Pro-Dafalgan, UPSA Laboratories, Rueil-Malmaison, France) is a soluble acetaminophen prodrug for intermittent intravenous infusion (2 g of propacetamol release 1 g of acetaminophen). This drug is often used initially to treat postoperative pain in France, before a switch to oral analgesic drugs.

Propacetamol and paracetamol have identical kinetics and adverse effects, except for possible local pain at the injection site.[8] However, administering propacetamol could entail a risk of allergic reactions such as contact dermatitis for health staff.[9] Guidelines on postoperative pain management developed by our institution, Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, recommend switching from propacetamol to paracetamol as soon as possible.[10] In addition, clinical guidelines on acute pain management in adults published in the United States recommend oral administration of drugs as soon as patients can take them.[11]

Hospital management and medical community representatives strongly recommended cost effective drug use. In view of the high percentage of inappropriate propacetamol administrations, an expert panel was convened (an anaesthetist of the orthopaedic department, two pharmacists, and a public health doctor) in order to improve pain management practices of the orthopaedic department.

Outline of context

This study was performed in Cochin Hospital, a teaching hospital with 1000 acute beds of the Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris group (the public hospital network for the Paris metropolitan area). The orthopaedic department of this hospital includes 37 beds, 11 surgeons, five consultant anaesthetists (responsible for postoperative pain management), and 30 nurses. In this department 1200 patients undergo surgery each year.

The Therapeutic Committee of the hospital agreed to the study. According to French policy, since the intervention was aimed only at doctors and nurses, it was not necessary to seek patient consent.

Assessment of problems and strategy for change

Details of approach taken

The general approach was to develop, implement, and assess the impact on practice of a local guideline focusing on both prescription and administration of drugs. Since the guideline would be used as a cost control strategy, we considered it important that an experimental or quasi-experimental design be used to verify that the guidelines did improve care.

We conducted a prospective, controlled, before and after study over 16 months. A pre-intervention observation period (September 1997 to March 1998) was followed by an intervention period (April 1998 to December 1998). The orthopaedic department served as the intervention group, and other surgical departments (general and digestive surgery, urology) of the hospital were the control group. Anaesthetists and nurses of control departments were unaware of the intervention and did not participate in any activity of the orthopaedic department.

Guideline development

In the orthopaedic department, the standard procedure for pain management was to start propacetamol immediately after surgery. Propacetamol injections were maintained as long as the patient felt pain. The guideline simply proposed to switch from propacetamol to oral analgesic as soon as the patient was able to eat solid food or take other oral drugs.

Paracetamol-dextropropoxyphene was preferred to paracetamol alone at the time of switch because it was the most prescribed oral drug for postoperative pain in the orthopaedic department. Too many changes could result in less compliance with the guideline. This combination (a level 2 analgesic according to the World Health Organization's classification[12]) is considered at least as effective as paracetamol alone (a level 1 analgesic)[13] and is recommended by Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris guidelines when paracetamol alone is ineffective.[10]

The guideline also included comparison of daily costs of propacetamol (Fr80) and oral drugs (Fr1.30).

Intervention

We implemented the local guideline in various ways.

* For doctors, we used a process of local consensus. Prescribing anaesthetists approved the new guideline during one of their daily staff meetings. The guideline was also formally approved by the head of the orthopaedic department. To allow nurses to switch from intravenous to oral analgesic, the anaesthetist responsible for a patient had to write on the patient's chart, each time propacetamol was ordered, "switch to oral analgesia as soon as the patient eats or takes other oral drags"

* For nurses, a one hour educational presentation was made by the expert panel. Four meetings were held in April 1998; to allow all nurses to attend one of them, the meetings were held at different times of day. During these meetings, the expert panel discussed the guideline, compared the effectiveness and cost of paracetamol-dextropropoxyphene and propacetamol infusions, showed the potential cost savings for the department, and answered all questions about the guideline and potential barriers to its application. Nurses' lack of experience in managing narcotic analgesics and lack of confidence in their ability to manage pain play an important role in their behaviour.[14] For example, the notion that intravenous medication is better than oral medication is common among patients and health professionals. Thus, the expert panel pointed out that the slow release of acetaminophen from the prodrug was responsible for the similar kinetics of the two routes and that, according to Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris guidelines, the combination of paracetamol and dextropropoxyphene is more effective than paracetamol alone.

* Posters presenting the new guideline and signed by the management of the department (the surgeon, head of the orthopaedic department, chief nurse, and chief anaesthetist) were displayed in all the nurses' offices after the meetings (figure 1).

[Figure 1 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

* Feedback on practice was provided six months after the guideline was implemented. The expert panel presented preliminary results to nurses and anaesthetists in four meetings and answered all questions raised by the participants.

Measurement of problem

We counted the number of propacetamol injections per patient and calculated the percentage of inappropriate injections during four audits performed in the orthopaedic department at one month before and at one, three, and six months after the intervention was implemented. During each audit (which covered three weeks of clinical practice) one investigator (CR) analysed prospectively medical and nursing records of all patients from 12 hours after their surgical procedure until intravenous analgesic was switched to oral analgesic. When the investigator could not determine the appropriateness of the switch from reviewing the records, she questioned the patients. An inappropriate injection was defined as a propacetamol injection given when a patient was receiving any kind of solid food or oral drug. All data were rendered anonymous and handled confidentially.

In addition, we recorded the monthly consumption of propacetamol injections per 100 hospitalised patients from eight months before to eight months after the intervention was implemented, both in the orthopaedic department (intervention) and in the other surgical departments (control). These data were derived from the pharmacy computerised database and from the hospital information system.

We calculated the standard direct costs of one injection of propacetamol and of one administration of paracetamol, including the costs of the drug and of the medical device used for the injection, and time spent by the nurse (estimated at four minutes for propacetamol and one minute for paracetamol). These costs were drawn from the hospital's financial database. To estimate savings attributable to implementing the guideline, we applied these costs to the average number of injections per patient observed during the audit immediately before and after the intervention. Assuming that the practices observed during these two audits were representative of the practice in the orthopaedic department, we estimated the annual cost savings that could result from the application of the new guideline. We also estimated the cost of the intervention, including labour cost.

Statistical analysis--We used a two tailed formulation to test the null hypothesis that the monthly use of propacetamol injections per 100 patients was unchanged by the intervention. We performed Student's t tests to compare use of injections before and after the intervention and calculated 95% confidence intervals.

Results of assessment

All the anaesthetists and 29 of the 30 nurses from the orthopaedic department attended an educational meeting.

The table gives the results of the four audits at one month before and at one, three, and six months after the intervention. The mean number of injections per patient decreased from 6.81 before the intervention to 2.36 at six months after. The mean number of injections per patient declined between the first audit and the second, third, and fourth audits by 3.90 (95% confidence interval 3.30 to 4.50), 3.36 (2.70 to 4.00), and 4.45 (3.83 to 5.08) respectively (P [is less than] 0.0001). The percentage of propacetamol injections that were inappropriate decreased from 74% (68% to 78%) in the first audit to 47% (39% to 56%), 49% (41% to 57%), and 40% (31% to 50%) in the second, third, and fourth audits respectively.

Figure 2 shows the monthly consumption of propacetamol injections in the orthopaedic department and other surgical departments in the eight months before and eight months after the intervention. In the orthopaedic department the mean monthly consumption before intervention was 553.9 injections per 100 patients and was 233.0 after the intervention; in the other surgical departments mean monthly consumption was 227.5 and 255.5 respectively. Thus the monthly consumption of injections decreased by 320.9 (192.4 to 449.4) in the orthopaedic department (P=0.0007) and increased by 28.0 (-14.2 to 70.2) in the other surgical departments (P = 0.177).

[Figure 2 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

The mean cost per patient for acetaminophen analgesia decreased from 14 [pounds sterling] before the intervention to 6 [pounds sterling] after the intervention. We projected the annual cost reduction to be 15 100 [pounds sterling]. We estimated the cost of the intervention to be 970 [pounds sterling]. Thus, the cost of the intervention was recuperated within three weeks.

Lessons learnt and next steps

Our study shows that guidelines can be effective when they are simple and presented in an attractive and easily accessible format,[15] do not require too much change to existing routines, and are implemented using validated and low cost strategies.[16] The effectiveness of educational interventions has been questioned.[3-5] Such interventions can improve professionals' behaviour when, as in this study, they specifically address the need of health professionals, are based on actual working practices,[17] use interactive techniques such as discussion groups,[18] and are associated with other effective implementation strategies such as reminders.[3-5]

Until now, insufficient attention has been focused on nurses' role in implementing guidelines for prescribing practice. A recent systematic review identified only 18 studies evaluating the introduction of guidelines that targeted nurses, of which only five targeted nurses and doctors.[6] Our intervention was meant to change both doctors' and nurses' behaviour, and nurses played a major role in the success of the intervention since they decided when to switch from intravenous to oral analgesic according to patients' health status. Our study provides some evidence that strategies shown to be most effective in changing doctors' behaviour are also effective in changing nurses' behaviour. However, further studies performed in other settings are necessary to confirm these results.

We evaluated the impact of implementing guidelines on the process of care rather than patient outcome. Measuring outcome may be an insensitive tool to analyse the quality of care.[19-22] In particular, statistical analysis requires an adequate number of outcomes for the results to be meaningful. In contrast, indicators of process of care can better monitor performance of care when evidence shows that an intervention is effective.[23]

We followed prescribing patterns for only eight months after implementation of the intervention, so we do not know if the intervention will remain effective in the long term. However, the use of posters alone has been shown to be a simple and inexpensive method to sustain the effect of guidelines.[14 24]

Results of audits of analgesia use for patients in orthopaedic department before and after implementation of guideline

(*) Comparison of first audit with each of the successive audits: P<0.0001 (Student's t test).

What is already known on this topic

Clinical guidelines are essential tools to reduce inappropriate use of drugs, but they should be supported by implementation strategies of proved benefit

What this study adds

Simple guidelines can be effective in improving practices and saving costs when they are locally implemented

Strategies shown to be the most effective in changing doctors' behaviour are also effective in changing nurses' behaviour

Educational interventions can improve health professionals' behaviour when they are based on actual working practices, use interactive techniques such as discussion groups, and are associated with other effective implementation strategies

Contributors: CR participated in designing the protocol, collected the data, participated in data analysis, and wrote the paper. OC initiated the research and participated in designing the protocol; performing the intervention; collecting, analysing, and interpreting the data; and writing the paper. JPL participated in designing the protocol, performing the intervention, and writing the paper. G-RA performed the statistical analysis and participated in interpreting the data and writing the paper. GH participated in designing the protocol and interpreting the data and contributed to the paper. PD initiated the research; discussed core ideas; participated in designing the protocol, performing the intervention, and analysing and interpreting the data; and wrote and edited the paper. OC and PD are guarantors for the study.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

[1] Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Avorn J. Improving drug prescribing in primary care: a critical analysis of the experimental literature. Milbank Q 1989;67:268-317.

[2] Grilli R, Lomas J. Evaluating the message: the relationship between compliance rate and the subject of a practice guideline. Med Care 1994;32:202-13.

[3] Grimshaw JM, Russel IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet 1993;342:1317-22.

[4] NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Effective health care. Implementing clinical practice guidelines: can guidelines be used to improve medical practice? Effective Health Care 1994;8:1-12.

[5] Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. Can Med Assoc J 1995;153:1423-31.

[6] Thomas L, Cullum N, McColl E, Rousseau N, Soutter J, Steen N. Clinical guidelines in nursing, midwifery and other professions allied to medicine. In: Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Library. Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software, 1999.

[7] Waddell DL. The effects of continuing education on nursing practice: a meta-analysis. J Continuing Educ Nurs 1991;22:113-8.

[8] Depre M, Van Hecken A, Verbesselt R. Tolerance and pharmacokinetics of propacetamol, a paracetamol formulation for intravenous use. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 1992;6:259-62.

[9] Reynolds JEF, Parfitt K, Parsons AV, Sweetman SC. Martindale. The extra Pharmacopoeia. 31st ed. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 1996.

[10] Delegation a l'evaluation Medicale. Direction de la prospective et de l'information medicale. Assistance Publique-Ho pitaux de Paris. La prise en charge de la douleur post-operatoire (recommandations de pratique clinique). Paris: Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, 1994.

[11] Carr DB, Jacox AK, Chapman CR. Acute pain management in adults: operative procedures. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1992. (Quick reference guide for clinicians No 1. AHCPR Publication No 92-0019.)

[12] World Health Organization. Treatment of cancer pain. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO, 1997:18.

[13] Li Wan Po A, Zhang WY. Systematic overview of co-proxamol to assess analgesic effects of addition of dextropropoxyphene to paracetamol. BMJ 1997;315:1565-71.

[14] Nash R, Yates P, Edwards E, Fentiman B, Dewar A, McDowell J, et al. Pain and the administration of analgesia: what nurses say. J Clin Nurs 1999;8:180-9.

[15] McDonald CJ, Overhage JM. Guidelines you can follow and can trust: an ideal and an example. JAMA 1994;271:872-3.

[16] McNally E, de Lacey G, Lowell P, Wellch T. Posters for accident departments: simple method of sustaining reduction in x ray examinations. BMJ 1995;310:640-2.

[17] Cantillon P, Jones R. Does continuing medical education in general practice make a difference? BMJ 1999;318:1276-9.

[18] Davis D, Thomson MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education. Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA 1999;282:867-74.

[19] Davies HT, Crombie IK. Assessing the quality of care. BMJ 1995;311:766.

[20] Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD. Quality of health care: measuring quality of care. N Engl J Med 1996;335:966-70.

[21] McKee M. Indicators of clinical performance: problematic, but poor standards of care must be tackled. BMJ 1997;315:142.

[22] Hammermeister KE. Participatory continuous improvement. Ann Thorac Surg 1994;58:1815-21.

[23] Mant JS, Hicks N. Detecting differences in quality of care: the sensitivity of measures of process and outcomes in treating acute myocardial infarction. BMJ 1995;311:793-6.

[24] Auleley G-R, Ravaud P, Giraudeau B, Kerboull L, Nizard R, Massin P, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa ankle rules in France. JAMA 1997;277:1935-9. (Accepted 8 June 2000)

Editorial by Smith

Department of Pharmacy, Hopital Cochin, 27, rue du Faubourg Saint-Jacques, 75006 Paris, France

Claire Ripouteau pharmacist resident

Ornella Cohort pharmacist

Georges Hazebroucq professor Orthopaedic Department, Hopital Cochin, Paris, France

Jean Patti Lamas anaesthetist consultant

Public Health Unit, Hopital Cochin Pierre Durieux associate professor

Guy-Robert Auleley physician

Correspondence to: P Durieux, Sante Publique, Faculte de Medecine, Broussais-Hotel Dieu, 15 rue de l'Ecole de Medecine, 75006 Paris, France (pierre.durieux@ egp.ap-hop-paris.fr)

BMJ 2000;321:1460-3

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group