Hanging on a wall in my office at the Ma'at Youth Academy is a picture of my father in his early thirties proudly holding a huge striped bass caught on the Richmond shoreline in Butler's Bay. Next to that hangs a photo of my husband beaming with a 33-inch striped bass from Whiskey Slough in the San Joaquin Delta. Finally, there's a shot of my two daughters, arms around each others' necks, proudly displaying a puny little bullhead that got tangled in their line while fishing off the Berkeley pier.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Our family history is not different from that of many other families of color living in the San Francisco Bay and Delta areas. Personal connections to the rivers, lakes, bay and ocean are an integral part of African-American culture--a culture enriched by childhood memories of catfish fries and gumbo that fed entire neighborhoods along the rivers and bayous of the South. It's not long ago that black families sent their children to the South during the summers to experience the magnificent scent of towering oak trees draped in Spanish moss and the crunching sounds of oyster shells along simple county roads that led to favorite fishing holes.

Unfortunately, a practice so vital to our lives and culture is being threatened.

A report published in 2000 by the San Francisco Estuary Institute concluded that contaminants in several species of bay fish were alarmingly high, confirming an earlier pilot study that indicated the potential hazards of eating fish from the bay. Local advisories warning of such fish contamination in the Northern California region have been emerging for several years. The heavily industrialized shorelines of Richmond, Martinez and Oakland led the San Francisco Regional Water Board's "Top 10" list for the bay's most toxic hot spots. Richmond sites accounted for one-third of the list, and one of the Richmond sites, United Heckathorn, remains an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Superfund site.

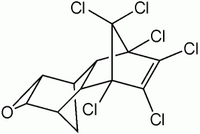

All fish species showed concentrations of one or more contaminants that were well above safe screening levels determined by the EPA. Fish tissue analysis indicated high concentrations of PCBs, mercury, DDT, dieldrin, chlordane and dioxins.

Mercury is an environmental hazard of particular concern, because it is transformed by bacteria into methylmercury, a much more harmful toxin. People are exposed to more mercury from eating fish, marine mammals and crustaceans than from any other source. In March 2004, a collaboration between the Food and Drug Administration and the EPA resulted in a new advisory that warned women of childbearing age and children about mercury levels and fish consumption. While this advisory acknowledged the importance and the benefits of fish consumption, it declared that nearly all fish contain traces of mercury. Mercury is a potent neurotoxin that impairs the nervous system. Fetuses and young children are most sensitive to mercury exposure, which can cause brain and nervous system damage, retardation of development, mental impairment, seizures, abnormal muscle tone and problems in coordination.

Race and Environmental Enforcement

California has some of the strongest environmental laws in the country; the problem lies in enforcement. Race, more than socioeconomics, is the dominant factor in the placement of toxic emitting sites, according to a groundbreaking report published by the United Church of Christ. As such, residents face chronic exposure to environmental hazards and related public health risks. Regulatory agencies do not provide equitable enforcement of environmental laws, forcing communities of color and low-income residents to shoulder the burden of protecting themselves. Recently, it required numerous telephone calls, letters and emails to five different agencies over several months just to obtain a sign alerting residents to the hazards of consuming fish caught in the Richmond Harbor.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Community members do not have the luxury to wait for enforcement. Communities residing in Richmond's Iron Triangle--Parchester Village, North Richmond and San Pablo--live alongside some 350 toxic emitting facilities, waste storage facilities and chemical manufacturing plants such as the Chevron/Texaco refineries. Neighborhood demographics reveal that a majority of residents are people of color, and more than half live below the poverty line. To many environmental justice and anti-racism advocates, it comes as no surprise that Contra Costa County has the highest amount of hazardous materials per capita in the state.

In response to such threats and inaction by authorities, a group of local youth in Richmond, members of the Ma'at Youth Academy (MYA), has assumed a more proactive approach to addressing public and environmental health issues in the community. Graduates of MYA's Community and Global Ecology program are recruited to participate in our Youth Environmental Ambassadors of Health (YEAH!) leadership program. YEAH!, which requires a one-year commitment, equips youth with the scientific knowledge to link aquatic environmental hazards to subsistence fishing and fish consumption. With these skills, the youth ambassadors can promote community health.

In 2001, YEAH! students assisted in designing and leading a community-based study investigating the fishing habits, fish consumption patterns, health advisory awareness and the risk of mercury contamination among the local population in Contra Costa County. The study's population was shore-based anglers fishing at the Richmond Harbor and the San Pablo Reservoir. A total of 132 anglers were surveyed. Seventy percent were Asian, African American, or Latino. Typical household size was six or fewer persons, with almost half including children ages five and younger. English was the most common household language, followed by Spanish and Laotian.

The majority of those surveyed--73 percent--indicated that they routinely ate fish caught from the bay, including bass and white croaker (kingfish), both currently on bay fish consumption advisories due to contamination. Initial research analyses revealed that many local residents were fishing in highly contaminated spots and unaware of local fish consumption advisories. Subsequent data showed that many residents who became aware of the advisories continued to eat bay fish in excess of the California EPA-recommended levels.

During the course of the study, public awareness of contaminants in bay fish dramatically increased. Yet residents stated that they had no intention of changing their fishing or consumption behavior for both cultural and economic reasons. How can advocates convince folks who rely on the bay for subsistence fishing and recreational sport to change their behavior? First by providing healthy alternatives. MYA does not advocate that folks stop eating fish, but there are certain fish species that are less contaminated than others. Secondly, MYA believes that a more aggressive approach is necessary to clearly demonstrate the public health effects from consuming fish with elevated contaminant levels.

To that end, MYA is undertaking a biomonitoring study to investigate the total "body burden"--or complete amount of mercury intake from eating commercial or sport fish--on local women and children. This effort is part of a larger community-led initiative to increase public awareness and to provide dietary guidance and encourage dietary changes.

Additionally, MYA is working with local legislators to expand biomonitoring and require regulatory agencies to determine screening levels and educate the public about hazardous chemical exposures. Through these efforts and other collaborations with groups such as Physicians for Social Responsibility and the National Resource Defense Council, we hope to raise awareness at the state level about the problem of mercury contamination from gold mines and refineries.

Fish are important to many cultures, and cautioning communities of color not to consume fish is not the solution. Cleaning up the bay now and for future generations is the ultimate goal.

Sharon Fuller is the founder and executive director of the Ma'at Youth Academy.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Color Lines Magazine

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group