Studies over the past seven years increase the concern that pregnant women who used the synthetic hormone DES may have an increased risk of breast cancer, according to a recent report of a task force convened by the Department of Health and Human Services. However, a cause-effect relationship is still unproven, and the excess risk is similar to that for a number of other breast cancer risk factors.

The report also stated that the daughters born to the women as a result of those pregnancies--who thus were exposed to the drug before birth--may have an increased risk of dysplasia, a condition of the cervix and vagina that sometimes may lead to cancer. However, whether this actually increases the risk of cancer is "DES daughters" is still unclear, the task force cautioned.

The report recommended that information about the risks of DES exposure should continue to be sent to all physicians and to DES mothers and their daughters.

The DES Task Force was convened in 1985 to review the results of studies on the effects of the drug published since an earlier task force investigated the problem in 1978.

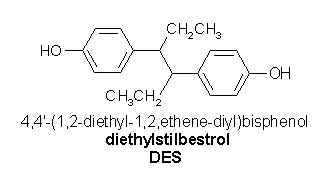

DES is a synthetic hormone with the tongue-twisting chemical name diethylstilbestrol. It was developed in England in 1938. During the 1940s, 50s, and 60s and even into the 1970s, perhaps 2 million pregnant women were given DES to prevent miscarriage. In some cases, the drug was given even in normal pregnancies, where there was no special risk of miscarriage.

In 1971, FDA ordered drug manufacturers to include a warning in the labeling of DEs and other estrogens that these products were not to be used during pregnancy. The warning was added after studies revealed an apparent increase in the risk of vaginal adenocarcinoma--a type of cancer--in young girls exposed to DES before birth. A special FDA Drug Bulletin was issued to alert physicians to the possible toxic effects of DES.

In 1978, the first DES task force, established by the then Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, reviewed the data on the risk of adenocarcinoma in DES daughters. Subsequent reports indicated that the risk wasn't as great as originally feared. Similarly, fewer daughters than expected had adenosis, a benign (noncancerous) abnormality of the vagina.

What was known about breast cancer in DES mothers at the time of the 1978 task force was based on a study of women who, while they were pregnant, had participated in a clinical trial of DES at the University of Chicago in 1951. The study reported 32 breast cancers in a group of 693 women exposed to DES, compared to 21 cancers among 668 women who did not take the drug. Though the numbers were too small to rule out the possibility of chance or coincidence, the excess risk and the fact that the cancers appeared to develop earlier in the DES-exposed women did raise concerns.

The 1985 DES Task Force reviewed a 1980 update of the Chicago study, which showed that the total number of breast cancers detected in DES-exposed women had increased by two, to 34, but the number in the unexposed women had increased by seven, to 28. Thus, said the 1985 task force, "the excess risk of breast cancer noted during the first 20 years of followup was somewhat diminished with additional followup beyond that time."

In addition, four new studies were reviewed by the 1985 task force. Two were follow-ups of randomized trials of DES use in pregnancy. The larger of the two showed little or no excess risk of breast cancer among exposed vs. non-exposed women. However, in the smaller trial, involving diabetic women, four breast cancers developed among the 50 women given DES, while none developed in the 96 women not given the drug.

The task force looked at two observational studies in which the records of women who took DES during pregnancy were compared to those of a group of unexposed women of similar age and race who had given birth at about the same time. These studies showed a 50 percent greater risk of breast cancer associated with DES exposure. The risk increased with duration of follow-up, rising approximately twofold for those followed for 20 years or more.

The 1985 task force concluded that there is now greater cause for concern than there was in 1978, although a casual relationship has not been established.

The task force members cited a number of factors affecting their conclusions, including the difficulty of assessing whether the excess risks are due to the drug or to spontaneous abortion and other known risk factors. The group also questioned whether the DES mothers were more likely to have intensive medical attention and thus higher rates of cancer diagnosis. They noted as well that risk related to length of follow-up were not consistent among the four studies.

As for the health of DES daughters, the 1978 report focused on the increased risk of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Concerning another form of cancer, squamous cell cancer of the cervix, the 1978 report said the risk was the same in exposed and unexposed women. This conclusion was based partially on results of the initial screening examination of DES daughters in the National Cooperative Diethylstilbestrol Adenosis (DESAD) Project, a large collaborative study involving four groups of DES-exposed women.

The 1985 task force reviewed a report of the first seven years of follow-up of these women, which showed that DES-exposed women experienced a significantly higher incidence of dysplasia--a growth of abnormal tissue that may or may not progress ot squamous cell cancer. Although the relationship between DES exposure before birth and the risk of subsequent development of squamous cell cancer is not proven, the new DESAD findings indicate this is a possibility that requires further study, the task force said.

However, the task force cautioned that these conclusions are based on only one study and that issues related to the clinical findings, epidemiology and pathology need to be studied further. "Because of these issues, the implications of these results for the development of squamous cell cancer remain unclear," the task force said.

The task force urged physicians who prescribed DES and other estrogens to prevent pregnancy complications between 1940 and 1972 to inform their patients about the possible increased risk of breast cancer.

Women should be encouraged to question their physicians about their own risk for developing breast cancer and ask for advice about the need for follow-up care for their off-spring. Those who know they were given DES in the past should tell their present physicians in order to assist in their follow-up and management, the 1985 report stated.

DES daughters with dysplasia should have careful medical follow-up since in some women this condition may evolve into cancer.

The screening recommendations for DES mothers are the same as the National Cancer Institute's recommendations for all women. They include monthly breast self-examination and a physical examination of the breasts by a physician at suitable intervals, usually annually.

Mammography (X-ray examination of the breasts) may be considered for women 35 or older with a personal history of breast cancer; for women 40 or over with a family history of breast cancer; and for all women over 49. Mammography would be indicated for any women with a lump or other symptom suggesting breast cancer.

The 1978 recommendations for screening DES daughters are still appropriate, the 1985 task force said. In addition to initial screening at age 14, these women should be examined periodically by a physician who can detect sutble changes in the cervix and vagina. They should have a yearly pelvic examination, Pap smear and, if necessary, a biopsy. Should any abnormalities be found, they should be seen promptly by a physician experienced in use of a colposcope, an instrument for examination of vaginal and cervical tissues by means of magnifying lenses.

The 1985 task force did not review the literature related to DES-exposed sons, in which some studies have reported an increased risk of certain genital abnormalities. However, the report said the general recommendations made in 1978 still appear appropriate--that is, for a careful history and thorough medical examination to detect abnormalities.

Follow-up studies of DES-exposed women and their off-spring should continue to be carried out and supported by the Department of Health and Human Services, the task force said. In addition, the group suggested investigations among the DES-exposed of factors such as exposure to other estrogens, radiation and smoking and possible interactions of these factors with the DES exposure. Hormonal and reproductive problems in both daughters and sons should also be studied, as should viral infections such as herpes.

Results of research projects recommended by the task force may not be available for several years. However, many of the group's recommendations relating to the dissemination of information to physicians and the public have already been implemented, including an article in FDA's December 1985 Drug Bulletin, which is sent to 1 million health professionals in the United States, including virtually all physicians.

In the meantime, DES mothers and their daughters and sons can get information through the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Information Service via a toll-free telephone service. The number is 1-800-4-Cancer.

COPYRIGHT 1986 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group