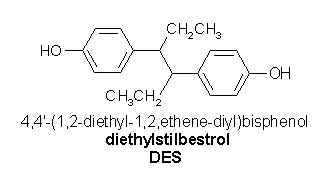

In the 1950s and 1960s, physicians commonly prescribed a drug called diethylstilbestrol (DES) to prevent miscarriage and premature birth. The safety of the drug, a synthetic form of the sex hormone estrogen, was first challenged in 1971. Since then, numerous studies have found that daughters of women who had taken DES during pregnancy ran an increased risk of developing a rare cancer of the vagina and cervix. For DES-exposed sons, some studies demonstrated a link between the drug and genital abnormalities.

A scientific report in HORMONES AND BEHAVIOR (vol. 26, p.62-75) finds statistically significant evidence that males exposed to DES in the womb may undergo subtle alterations in brain function.

"This is the first evidence in human males that prenatal exposure to sex hormones -- specifically DES -- is involved in the development of both brain organization and sex-differentiated cognitive abilities," says principal investigator June M. Reinisch of the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction at Indiana University in Bloomington.

Reinisch and her colleague Stephanie A. Sanders, also at the Kinsey Institute, began their investigation by recruiting 10 male subjects age 9 to 21 who had been exposed to DES in the womb but who showed no signs of DES-related birth defects. The researchers also recruited 10 male siblings in the same age group who had not been exposed to DES during gestation.

The subjects and their brothers then took the Witelson Dichhaptic Shapes Test, an evaluation that measures brain lateralization, or the tendency to use one side of the brain while completing a task. The participants were first told to reach into a box containing unfamiliar geometric shapes, Sanders explains. After feeling the shapes, the subjects had to match the shapes in the box with those depicted in a picture, she says.

Correct matches among the DES-exposed group were evenly distributed between both hands, a response that is more typical of the way girls and women score on this test. (Men and boys tend to get better scores with the nonpreferred hand.) The brothers in the control group showed the typical male pattern. Both groups got the same number of right answers, Reinisch points out.

It may be that DES-exposed males use both sides of the brain in matching the shapes, a trait most commonly seen in females. That doesn't mean that DES-exposed males are more feminine than their nonexposed brothers, the researchers emphasized. The test results simply mean they go about the task differently than their brothers.

The researchers also administered another test, the Wechsler Intelligence Scales, to the boys and young men in the study. They discovered that the DES-exposed group scored lower than their nonexposed brothers on a spatial component of the test. In that component, subjects have a certain amount of time to find missing parts of a picture, complete a jigsaw puzzle, and perform other tasks that measure spatial ability. Males tend to perform better than females on this component, and the DES-exposed males again followed the feminine pattern.

These results do not suggest that males exposed to DES in the womb are less intelligent than their nonexposed brothers, Reinisch cautions. In fact, the overall IQ test scores for both groups were about the same, she notes.

However, Reinisch and Sanders believe that exposure to DES in the womb does--in a very subtle way -- change the way men approach certain tasks, especially spatial tasks. The researchers believe that by studying DES exposure, they may be better able to understand the powerful effects of natural hormones on the fetal brain before birth. Such research might help explain possible gender differences in the way the human brain functions, they say.

COPYRIGHT 1992 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group