The World Health Organization now recognizes migraine as one of the most disabling medical conditions. In the United States, annual direct medical costs of more than $1 billion represent only a fraction of the total cost of migraine, which is estimated to cost employers more than $13 billion each year. The 28 million Americans who have severe migraines report an average of one to five attacks per month of moderate to severe pain, usually unilateral and accompanied by other symptoms, such as gastrointestinal upset, photophobia, and phonophobia. The severity of attacks and the related symptoms vary widely among patients. The importance of individualizing therapy to the specific needs of each patient is emphasized in a recent review by Silberstein.

Accurately diagnosing the condition, educating patients, and identifying comorbidities are essential steps in the management of migraine. Headache diaries can validate the pattern of attacks and help the physician develop treatment goals. Headache severity and disability scales, such as the Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS) or the Headache Impact Test, can be used to quantify headache morbidity and stratify patients for treatment.

Screening patients with migraine for conditions of increased prevalence (e.g., Raynaud's disease, depression, mitral valve prolapse, anxiety disorders) facilitates patient care and helps the physician select antimigraine treatment with specific characteristics to ameliorate comorbid conditions. Specific treatment of migraine is available to manage acute attacks and reduce the frequency and severity of attacks. Many patients benefit from a combination of acute and prophylactic therapy.

Acute treatments generally are classified as nonspecific (symptomatic) or migraine-specific. The choice of treatment strategy and individual agent depends on many factors, including headache severity and frequency; characteristics of the attack; patient characteristics and comorbidities; and drug characteristics, including efficacy, side effects, route of administration, and potential for overuse. Acute treatments should not be used more than two to three days per week because of their potential for adverse effects such as rebound headache.

Nonspecific treatments include analgesics and antiemetics to combat the most troublesome symptoms for patients with mild to moderate migraine. Evidence supports the use of aspirin and several nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, with or with-out caffeine, to relieve symptoms of acute migraine. Nonoral administration may be useful because of vomiting and delayed gastric absorption during migraine attacks. Antiemetics such as prochlorperazine can control vomiting and relieve migraine. Although opioids are effective, they usually are reserved for rescue medication or for the treatment of pregnant women with migraine. Use of barbiturate medications is not supported by the evidence and is associated with a significant risk of overuse and withdrawal problems.

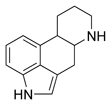

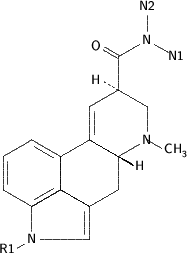

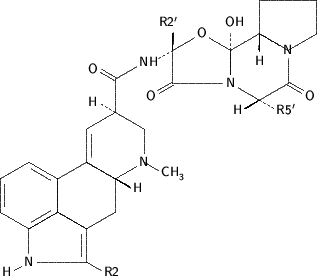

The specific antimigraine drugs, ergots and triptans, are potent 5-HT1B/1D agonists and are indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe migraine episodes. Both classes of drugs are effective, but ergots have more side effects and are contraindicated in a range of conditions. Ergotamine and dihydroergotamine can be administered by various routes. Intravenous dihydroergotamine is used frequently for intractable migraine.

The triptans are more selective receptor agonists than the ergots and, thus, have fewer adverse effects. The currently available triptans vary in speed of onset, rate of headache recurrence, and efficacy. Clinical trials generally report "any response" or "complete pain-free" status two hours after the medication is used. Because the placebo effect can be marked in patients with migraine, results are most meaningful when the placebo response is deducted (i.e., therapeutic gain).

Triptans are most effective if taken early during the migraine attack. These drugs generally are safe except in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, but some triptans interact with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and other drugs, including propranolol. Nonoral preparations provide the fastest onset of action and may be necessary in patients with vomiting.

Of the oral triptans, almotriptan, eletriptan, and rizatriptan have the greatest efficacy and fastest onset of action. Although the choice of agent for each patient depends on efficacy, speed of onset, chance of recurrent symptoms, and side effects, patients show significant idiosyncratic response and may need to try several different types and strengths of triptans before finding one that best alleviates their symptoms.

Prophylactic treatments aim to reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks. They should be considered when migraine substantially interferes with the patient's life and in special circumstances, such as when there are contraindications to or severe reactions from acute treatment. Several classes of prophylactic drugs are available. The choice of agent depends on efficacy, potential for adverse effects, and impact on comorbidities. In general, prophylactic therapy should begin at a low dose and increase slowly until therapeutic effect or side effects are significant. An appropriate trial of prophylaxis requires several months at the full therapeutic dosage. Patients often benefit from a combination of medication and non-pharmacologic interventions (e.g., relaxation training, cognitive behavioral therapy, bio-feedback) in migraine prophylaxis.

The beta blockers, including propranolol, nadolol, atenolol, metoprolol, and timolol, are effective but may cause fatigue, sleep disorders, and decreased exercise tolerance. Although use of beta blockers is contraindicated in patients with congestive heart failure, asthma, Raynaud's disease, and type 1 diabetes, patients with angina or hypertension may benefit. Antidepressants are useful in patients with depression and certain anxiety disorders in addition to migraine, but only amitriptyline has evidence for prophylaxis of migraine. Patients taking effective dosages should be cautioned about dry mouth, weight gain, sedation, and other potential side effects.

The calcium channel blockers vary in efficacy against migraine. Flunarizine is reported to be effective. The evidence for nimodipine, nifedipine, and verapamil is difficult to interpret, and all have the potential for adverse events. Of the anticonvulsant drugs, divalproex sodium and sodium valproate are effective but have frequent side effects, including nausea, alopecia, tremor, weight gain, and sleepiness, as well as potentially serious congenital, hepatic, and pancreatic toxicities. Topiramate has shown ability to reduce migraine frequency and is associated with weight loss, but the studies were complicated by high dropout rates.

Less common prophylactic agents for migraine are riboflavin in dosages of at least 400 mg per day, butterbur (75 mg twice daily), coenzyme Q10, and feverfew. Injections of botulinum toxin also have been reported to reduce migraine over a 90-day period. The most effective migraine prophylactic, methysergide, causes endocardial or retroperitoneal fibrosis in rare cases. Because of these and other complications, a four-week drug-free interval is recommended after six months of treatment.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This review is a timely reminder that treating migraine is about much more than dispensing medications. Indeed, even the most potent drugs have only modest effect if taken alone. Recent data show that the rates of consultation for migraine are increasing rapidly and that the vast majority of migraine visits are to family physicians (Gibbs TS, Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Sam MC, O'Donovan CA. Health care utilization in patients with migraine: demographics and pat-terns of care in the ambulatory setting. Head-ache 2003;43:330-5). How does one make sense of all the current treatment information and provide good, personalized, patient-cen-tered migraine care, given the limitations of a busy practice? Two useful strategies are to define one's role as a coach and to selectively use the many available resources. As with other chronic conditions, migraine cannot be cured by physicians; however, we can assist patients and their families in living success-fully with the condition if we use our skills in continuous, comprehensive patient care.

An approach of working through the issues with the patient over a long period is much more successful than focusing on guilt and anger from repeated disappointments or perceived failures. In addition, many organizations and Web sites provide helpful resources such as patient diaries, the MIDAS and other assessment tools, and patient information. Good Web sites include those of the National Headache Foundation, the American Consortium for Headache Education, and the American Academy of Neurology. The choice of Web resources requires careful attention to ensure that patients receive accurate information and are protected from sites that seem designed to exploit their suffering.

Silberstein S. Migraine. Lancet January 31, 2004;363:381-91.

COPYRIGHT 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group