Dilantin

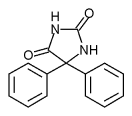

Phenytoin sodium (marketed as Dilantin® in the USA and as Epanutin® in the UK, by Parke-Davis, now part of Pfizer) is a commonly used antiepileptic. It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1953 for use in seizures. Phenytoin acts to damp the unwanted, runaway brain activity seen in seizure by reducing electrical conductance among brain cells. more...

History

Phenytoin (diphenylhydantoin) was first synthesized by a German physician named Heinrich Biltz in 1908. Biltz sold his discovery to Parke-Davis, which did not find an immediate use for it. In 1938, outside scientists including H. Houston Merritt and Tracy Putnam discovered phenytoin's usefulness for controlling seizures, without the sedation effects associated with phenobarbital. There are some indications that phenytoin has other effects, including anxiety control and mood stabilization, although it has never been approved for those purposes by the FDA.

Jack Dreyfus, founder of the Dreyfus Fund, became a major proponent of phenytoin as a means to control nervousness and depression when he received a prescription for Dilantin in 1966. Dreyfus' book about his experience with phenytoin, A Remarkable Medicine Has Been Overlooked, sits on the shelves of many physicians courtesy of the work of his foundation. Despite more than $70 million in personal financing, his push to see phenytoin evaluated for alternative uses has had little lasting effect on the medical community. This was partially due to Parke-Davis's reluctance to invest in a drug nearing the end of its patent life, and partially due to mixed results from various studies.

Dilantin made an appearance in the 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest by Ken Kesey, both as an anticonvulsant and as a mechanism to control inmate behavior.

Side-effects

At therapeutic doses, phenytoin produces horizontal gaze nystagmus, which is harmless but occasionally tested for by law enforcement as a marker for drunkenness (which can also produce nystagmus). At toxic doses, patients experience sedation, cerebellar ataxia, and ophthalmoparesis, as well as paradoxical seizures. Idiosyncratic side effects of phenytoin, as with other anticonvulsants, include rash and severe allergic reactions.

There is some evidence that phenytoin is teratogenic, causing what Smith and Jones in their Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation called the fetal hydantoin syndrome. There is some evidence against this. One blinded trial asked physicians to separate photographs of children into two piles based on whether they showed the so-called characteristic features of this syndrome; it found that physicians were no better at diagnosing the syndrome than would be expected by random chance, calling the very existence of the syndrome into question. Data now being collected by the Epilepsy and Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry may one day answer this question definitively.

Phenytoin may accumulate in the cerebral cortex over long periods of time, as well as causing atrophy of the cerebellum when administered at chronically high levels. Despite this, the drug has a long history of safe use, making it one of the more popular anti-convulsants prescribed by doctors, and a common "first line of defense" in seizure cases. Phenytoin may also cause gingival hyperplasia.

Read more at Wikipedia.org