Situation: First the crazy woman jeopardized her little kids' lives. Then she came at them--and you--with a cleaver-like edged weapon.

Lesson: Do what you know you must. Leave it to the rest of society to determine why the mentally ill, and children they endanger, go neglected. Be prepared for unwarranted hostility when ethnic bias and public ignorance make you out a murderer for "killing one of ours."

Her name is Cau Thi Tran. The media and others will later put her three names in multiple different sequences, but this is how she is referred to by most her community, and it is how her name will appear on her last official record, her autopsy.

Tran is slender, pretty and petite, no more than five feet tall, 25 years old. An immigrant from Vietnam to San Jose, Calif. She has developed a long and serious psychiatric history, laced with violent outbursts and assaults and involuntary commitments to mental institutions. She has been diagnosed with Psychotic Disorder, and given only a "fair" prognosis for the future. She has been determined to be "a danger to herself and others." Her small children have been in and out of foster care. She and her significant other have the kids at home now. Tran is supposed to be on psychotropic drugs to control her mental illness.

But she has stopped taking them. Cold turkey, instead of tapering off. This can lead to a phenomenon called "decompensation." If an epileptic has been controlling his seizures with Dilantin and suddenly breaks off, he may soon experience his worst grand mal seizure yet. And, if a psychotic stops taking the controlling drugs in the same abrupt fashion, she may soon experience the worst psychotic break in her mental health history.

On the evening of July 13, 2003, neighbors notice one of her little boys playing alone and venturing into the busy street. This is something they've witnessed before. One will later testify to having seen Tran strike her little ones sharply and repeatedly. This time, neighbor Joy Tamez sees something even more dangerous: Tran's two year old boy runs into the street in front of a truck. She grabs him just in time, saving him from death with inches to spare. She asks another neighbor, Dolores Salazar, to dial 9-1-1. The timeline is as follows.

At 8:58 PM, neighbor Dolores Salazar calls police and tells the dispatcher what has happened.

At 9:00 PM, uniformed San Jose PD Officers Thomas Mun and Chad Marshall respond to the call, told that the matter is in reference to unattended children.

Other calls are coming in from the neighborhood, reporting a violent, screaming argument at the address in question. At 9:03, communications advises the mother is possibly being assaulted by her boyfriend. Arriving at the scene, Marshall and Mun hear a loud, angry female voice inside. Both have been well trained in the dangers of interfering in the dreaded "domestic dispute." Their senses are on full alert as they approach the front door. They realize this could very quickly deteriorate into a very high-risk situation. At 9:04, Officer Mun requests restricted radio traffic due to the circumstances at the location.

At, 9:06, Mun's voice will come on the air with a message that chills the spine of every cop and dispatcher who hears it. Shots fired. EMS--the Emergency Medical Service--is needed urgently.

The Shooting

Dang Quang Bui, Tran's significant other, lets the officers in. He explains apologetically that Tran is crazy. As Marshall and Mun enter the small apartment, they see the two little boys are to their right, with Bui, and Tran is at their left, behind a room divider that flows into the kitchen.

Tran shrieks at the policemen in English, "I want you out!" Before they can attempt to calm her, she snatches up a gleaming piece of steel. It looks like a large kitchen knife to Officer Mun, and like a cleaver to Officer Marshall.

Both cops draw their pistols. Mun holds his in a low ready. Marshall steps between Tran and the children, to shield them with his body if she attacks them, since it is fresh in his mind that this call began as a potential child abuse case. His left hand is stretched out behind him to keep the children back and clear, and his SIG-Sauer P226 is in his right hand, muzzle down, finger clear of the trigger.

She moves along the room divider toward them, the steel gleaming menacingly in her hand. Marshall yells at her, "Drop the knife!" She is now only eight feet away from them. But she disobeys the command. Instead of stopping or dropping the weapon, her forward movement continues, her arm coming up shoulder high, as if to either chop downwards or throw the weapon. The cops can wait no longer.

Mun is bringing his gun up on her and is about to fire when he hears a single shot. Marshall has fired first, coming up one handed. A single shot blasts from the muzzle of his 9mm, and Tran jerks backward and falls supine on the floor, the blade flying from her hand to her right.

A department-issue Winchester Ranger SXT 9mm round has entered her left chest and pierced her heart, peeling open as it traveled and tearing a massive four centimeter by four centimeter hole in the back of that vital organ before stopping, fully mushroomed, in the muscles of her back.

EMS is called immediately, and the police do all they can for her in the moments after the shooting. But it is futile. Tran's death has been almost instantaneous.

Aftermath

San Jose is said to contain, proportionally, the largest population of people of Vietnamese descent in the United States. Within this tightly knit community, the prevailing feeling seemed to be primarily, "One of our own has been shot."

Because there is a public myth that guns are deadlier than edged weapons, a certain element of the public always thinks it's somehow unfair to shoot a person who "only had a knife." It has only been a little more than twenty years since Dennis Tueller's ground-breaking research proved something now known to virtually all police and well-trained armed citizens, but still not the general public: that the average adult male can close a distance of 21 feet and inflict a fatal stab wound in an average of 1.5 seconds.

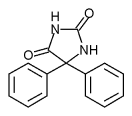

Added to this misinformation came a clueless misunderstanding about the weapon. What Tran turned out to be wielding was a kitchen implement popular in Thailand and Vietnam known as a dao bao.

Dao bao is pronounced "dow bow." It rhymes with "Ow! Ow," which is what anyone would utter when struck with it. Picture a rectangular cutting tool with over/under blades. The lower blade's edge is the primary chopping surface. A small space running the length of the blade separates it from the upper cutting edge, which is located in the center. This second edge, and the space below it, was developed for peeling large, tough-skinned Asian fruits and vegetables.

The device is, in essence, a half-size meat cleaver. I've had the opportunity to examine the particular dao bao that Tran was holding when she was killed. It was, unquestionably, a deadly weapon. The authorities sent Tran's dao bao to a cutlery manufacturer, with instructions to take a couple of genuine brand-new cleavers and compare them in terms of sharpness and cutting power. The cutlery professionals determined that Tran's weapon came dead in the middle between the two new, dedicated cleavers in its ability to cut and inflict wounds.

However, the media called her weapon a "vegetable peeler."

This was monstrously unjust, unfair, and untruthful. The public in this country, hearing the term "vegetable peeler" and never seeing a dao bao in size or weight perspective or examining its sharp lower edge, imagines a carrot peeler or a potato peeler. An innocuous little thing that is dull all around the outside and couldn't hurt someone even if its wielder tried. A cop who had fired to protect himself, his partner and two little kids from being chopped up with what effectively was a cleaver, was falsely painted to the public as someone who shot a small woman who wasn't armed with a real weapon.

The media, and the well-organized Vietnamese community in San Jose, clamored for the officer's scalp. Chad Marshall was ordered to go before the grand jury, facing indictment for Manslaughter or even Murder.

The Grand Jury Speaks

The San Jose Police Department places great emphasis not only on training, but the ability to document and explain that training. When the hearing convened on October 21, 2003, one department instructor after another was brought before the 18 citizens of the Grand Jury to explain why the officers were trained to deal with a situation like this exactly the way Officer Marshall did.

Marshall and Mun also took the witness stand. Each professionally recounted their perceptions of the short few seconds in which they'd had to take action. It was clear that Marshall genuinely grieved over having been forced to pull the trigger. The Grand Jury learned it was the accused, Chad Marshall, who had been the first person to attempt to provide first aid to Cau Thi Tran in the moments after the shooting.

I was brought in by the prosecutor's office to explain how the training evolved that the officers received, and the human dynamics that led up to that training. This included the lethality of the half-size cleaver, which would cause the sort of wound you'd expect from a Bowie knife in slashing mode--avulsive injuries. Body parts on the floor. Skulls cloven open.

It has been suggested the officers should have kicked the knife out of her hand. The Grand Jury learns a little about the speed of edged weapons in human hands, particularly the very fast hands of lithe and compact people, and that trying to kick a knife out of a fast moving hand is like trying to emulate the fantasy martial artists running up walls in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. They have learned that shooting to wound or shooting a knife out of a moving hand is a similar movie fantasy. It had been suggested that since the officers wore body armor, they were invulnerable; the Grand Jury learns that the armor covers only 30-percent or less of the body, and can be stabbed through by weapons like the 8" butcher knife Officer Mun reasonably mistook the dao bao for.

The Grand Jury heard evidence for seven full days. On Thursday, October 30, after three hours of deliberation, they returned No True Bill. In other words, they determined no crime had been committed by San Jose Police Officer Chad Marshall. Their verdict, in effect, was a ruling of justifiable homicide.

Lessons

The learning points in the justifiable and necessary shooting death of Cau Thi Tran encompass elements of firearms and ammunition and tactics, but go far beyond them. Let's discuss the hardware first, then the software.

Chad Marshall was using an excellent police pistol, the SIG-Sauer P226. It is an accurate gun designed to be "shootable" under stress with its first double action shot. It performed as intended when Marshall had to raise it and fire it in an instant, one-handed, with the other hand outstretched to shield the children from their armed and apparently homicidal mother. The Winchester Ranger ammunition also performed exactly as advertised, delivering an instant one-shot stop. With the proper ammunition, it has been proven many times, a 9mm pistol is up to the job, and this incident proved it yet again.

We will never know whether Tran had raised the knife to throw it or to slash with it as she continued her forward movement. In the end, it does not really matter. She was in an obvious state of psychotic rage, and whether the edged weapon is thrown or swung, it can still kill and still warrants the same response in self-defense.

The general public does not understand the dynamics of violent encounters. These officers did. After seven days of hearing testimony, so did the Grand Jury. Whether that body consists of 23 people, as is traditional in many jurisdictions, or 18 as in this case, the Grand Jury is the sounding board that determines whether or not there is reason to believe a crime has been committed warranting a full blown trial. In this case, they determined no crime had been committed by the police. The weight of the facts in evidence overwhelmingly supports their collective decision.

But for them to come to that decision, they had to be educated. The professional instructors and command staff of the San Jose Police Department had known such a day might come, and they were prepared. Their training was thoroughly documented. They were able, through the material witness testimony of their staff instructors and the expert witness testimony of outside consultants, to show the grand jury that what was done by the officers was the right thing to do. That it was reasonable and prudent. That it was within what the law calls "the common custom and practice" of dealing with such emergencies.

When the proverbial smoke has cleared, and the person who has pulled the trigger is being judged for that act, this documentation and authentication is critical. It is as critical for a private citizen as it is for the law enforcement officer. Fortunately, it was there to be used in this case, because of the top-notch training provided and documented by the police department.

There are other lessons here, too. This death was preventable. It just wasn't preventable by the officers who responded and were faced with deadly danger to the children and themselves.

Throughout human history, people have denied that loved ones who are insane have become as they are. It's not just an ethnic culture thing, it's a human nature thing. We love this family member, this close friend, this lover or spouse. We desperately want them to be normal, and it's easy for us to slip into rationalization and denial. This is what clearly happened in the case of Cau Thi Tran.

Her violence had been escalating in recent years. It went from screaming to physical assault, from wielding a shoe as a weapon to wielding scissors as a weapon in her most recent incident before the shooting. On the night of July 13, 2003, it escalated to attacking police officers with a lethal cleaver-type weapon. Her significant other, and perhaps other people close to her, were aware she had stopped taking her medication, but they had done nothing to correct that situation.

No Villians

I write this not to blame those who loved Cau Thi Tran. I write it because it is the truth. There were no villains in that small apartment in San Jose when the single pistol shot was fired that night, only victims. Two little boys whose mother was killed in their presence. Cau Thi Tran, of course, a victim of her own psychosis. And two police officers who were profoundly traumatized by what happened. Chad Marshall did what he had to do, and Thomas Mun was about to do the same thing. Each should take pride in having been able to perform under pressure as they were trained and save lives. Yet I am sure neither takes any particular pride in the death of the woman who came at them with the deadly dao bao.

The public needs to be reminded the violent acts of their mentally ill loved ones can bring injury or death upon them, and the diseased mind is no excuse. We need to make it socially acceptable to reach out and seek help for people like Cau Thi Tran before their situation predictably worsens and they act out as she did and end up as she did.

The public also needs to understand how these things happen. It's uncertain whether more mental health care and intervention might have saved Tram from the psychiatric diagnoses of her on record, it does not look terribly likely. But for a cop who put his body between a mad-woman with a weapon and the children in the line of her homicidal fury to be pilloried for firing a pistol to stop her, is simply wrong. The public needs to be as well educated in these matters as the Grand Jury that understood well enough to exonerate him.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Publishers' Development Corporation

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group