Although ingestion of dust from lead-based paint is the most common source of lead exposure among children in the United States (1), lead also can be present in unsuspected objects. Ingestion of these objects can result in elevated blood lead levels (BLLs). This report describes an investigation by the Deschutes County Health Department and the Oregon Department of Human Services of lead poisoning in a boy who swallowed a medallion pendant from a neckace sold in a toy vending machine. The investigation resulted in a nationwide recall in September 2003 of the implicated toy necklace. Clinicians and caregivers should consider lead poisoning in any child who ingests, or puts in his mouth, a metal object. Cases of lead poisoning should be reported immediately to public health authorities to prevent other children from being exposed to the same sources of lead.

In July 2003, a boy aged 4 years was taken to a physician in Oregon after several days of abdominal cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea without fever. His symptoms resolved until 1-2 weeks later when he had another bout of vomiting and abdominal pain. He was returned to his physician, and his condition was diagnosed as probable viral syndrome and anemia of undetermined etiology.

Two days later he was brought to the emergency department with worsening symptoms, including constipation and inability to eat or sleep because of his abdominal pain. An abdominal radiograph showed a metallic object in the stomach with no evidence of obstruction; repeat laboratory studies showed a persistent normocytic anemia. Initially, the object was believed likely to pass on its own; however, on the next day, an abdominal computerized tomography showed the object more superiorly located. Endoscopy was performed, resulting in retrieval of a medallion pendant (along with a quarter) from the boy's stomach.

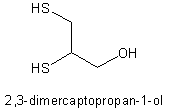

Three days later, the boy returned with edema of the left cheek and gingiva, suggesting either a dental abscess or excessive biting of the cheek. Concern that the cheek bite might have been caused by a seizure prompted testing of his BLL, which was 123 [micro]g/dL (CDC's level of concern = [greater than or equal to] 10 [micro]g/dL). The boy was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for intravenous chelation therapy. No evidence of encephalopathy was found; a sleep electroencephalogram was normal. The boy was treated with dimercaprol (i.e., BAL) followed by calcium disodium versenate (i.e., EDTA), and his BLL decreased to 57 [micro]g/dL. He was switched to oral succimer (i.e., DMSA), but received a repeat course of EDTA when his BLL increased to 69 [micro]g/dL. After three courses of succimer, his BLL was <40 [micro]g/dL. The boy's zinc protoporphyrin level peaked at 556 mM/ M (normal: 25-65 mM/M). Peripheral blood smear showed basophilic stippling. Subsequently, neurodcvelopmental, cognitive, and speech therapy evaluations of the boy all showed appropriate development.

An environmental investigation of the boy's home, which was built in 1996, did not reveal any additional sources of lead exposure. A sibling, aged 6 years, had a BLL of <5 [micro]g/dL.

The medallion retrieved from the boy's stomach was reportedly purchased from a toy vending machine in Oregon, approximately 3 weeks before it was retrieved. The state environmental quality lab found the medallion's contents to be 38.8% lead (388,000 mg/kg), 3.6% antimony, and 0.5% tin. Similar medallions purchased from toy vending machines in other areas of Oregon were found to have similar high proportions of lead (44% and 37%). These medallions are round, measuring approximately 7/8 of an inch in diameter, gray in color, with a symbol on one side (Figure). State health officials notified the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission; a national voluntary recall * was announced on September 10, 2003, of approximately 1.4 million of the metal toy necklaces. A distributor of the medallions reported that they had been manufactured in India and distributed throughout the United States. Oregon health officials cautioned that more of the medallions might still be sold in vending machines in the state (2).

Acknowledgments

WL Pickner, Oregon Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, Oregon Dept of Human Svcs, Health Svcs; Deschutes County Health Dept, Bend; A Jaffe, MD, Oregon Health and Science Univ, Portland, Oregon. MW Shannon, MD, Children's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

* Available at http://www.cpsc.gov/cpscpub/prerel/prhtml03/03178.html.

References

(1.) CDC. Surveillance for elevated blood lead levels among children--United States, 1997-2001. In: CDC Surveillance Summaries (September 12). MMWR 2003;52 (No. SS-10).

(2.) Office of Public Affairs, Oregon Department of Human Services. Oregon lead poisoning case leads to national recall. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Department of Human Services, 2003. Available at http://www.dhs.state.or.us/news/2003news/2003-0923.html.

JL VanArsdale, MD, BZ Horowitz, MD, Oregon Health and Science Univ, Portland; TA Merritt, MD, St. Charles Medical Center, Central Oregon Pediatric Associates; DW Peddycord, E Severson. KM Moore, NJ Pusel, Deschutes County Health Dept, Bend; RD Leiker, MS, BR Zeal, MJ Scott, Oregon Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program; MA Kohn, MD, Oregon Dept of Human Svcs, Health Svcs.

COPYRIGHT 2004 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group