A 34-year-old man presented with symptoms of left flank pain, gross hematuria, chills, and a cough productive of green, blood-streaked sputum. He was admitted to the hospital for treatment with fluids and pain control. On the second day after hospital admission, the patient complained of worsening shortness of breath, chills, and right-sided pleuritic chest pain. His medical history was remarkable for congenital agenesis of the right kidney and for illicit drug use.

A physical examination showed a well-developed man who was in considerable distress and was unable to get comfortable in the bed. Measurements of vital signs revealed the following., temperature, 102.5[degrees]F; pulse, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; BP, 110/69 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 97% on room air. A lung examination was remarkable for coarse breath sounds and crackles at both bases, greater on the right side than on the left. No cyanosis or clubbing was detected.

Laboratory findings were the following: WBC count, 16.1 cells/[mm.sup.3]; platelets, 362,000 cells/[mm.sup.3]. Sputum grew Streptococcus pneumoniae. The findings of a chest radiograph that was taken on hospital admission were normal. A CT scan of the abdomen made after hospital admission showed a small stone in the left proximal ureter and hydronephrosis. Repeat chest radiographs taken on the second day of admission (Figs 1, 2) showed diffuse bilateral linear branching radiodensities that were greatest in the lower lungs. The patient underwent abdominal CT scans, which revealed high-density foci in the lungs, anterior right ventricle of the heart, apex of the left ventricle, liver, and kidney. Blood samples were taken.

[FIGURES 1-2 OMITTED]

What is the diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Mercury injection

The patient's initial blood mercury level was 530 [micro]g/dL, and the first urine collection sample had a mercury level of 2,767 [micro]g for 24 h. The sphygmomanometer in the patient's room was broken. The bulb from the broken sphygmomanometer was found in a drawer in the patient's room with a tourniquet. A radiograph of the left hand, from which an infiltrated IV line had been removed, revealed a small area of high-density material.

DISCUSSION

There are the following three potential modes of mercury toxicity: ingestion, inhalation, and injection. Acute ingestion is generally well-tolerated, as for > 200 years mercury was used to treat intestinal maladies. (1) By contrast, inhalation of vaporized metallic mercury often can cause insidious mental status changes, including behavioral changes, insomnia, depression, and hallucinations. (2) Other symptoms associated with mercury poisoning are anemia, renal insufficiency, stomatitis, colitis, peripheral neuropathy, and tremors. (1) Perhaps the most colorful description of chronic mercury toxicity is the "Mad Hatter" in Alice in Wonderland, a character whose personality was derived from the effects of illnesses seen in workers exposed to mercury salts and vapors in the hatting industry in the 19th century. (3) Low-level mercury vapor exposure still remains a significant public health problem because of workplace and household exposures such as mercury-containing latex paints. (2) Exposure to high concentrations of vaporized elemental mercury can be fatal and can cause acute pulmonary symptoms, including pulmonary edema, interstitial emphysema, and pneumothorax. Metal fume fever can develop with fever, chills, dyspnea, and a metallic taste in the mouth followed by stomatitis, lethargy, confusion, colitis, and vomiting. (4)

IV elemental mercury injection is infrequent, with reports scattered through the medical literature of accidental injections, suicide attempts, and iatrogenic injections from metallic mercury used as a anaerobic seal on blood gas-sampling syringes. (3) There are even athletes who deliberately have given themselves IM and IV mercury injections in the false hope of developing strong musculature, or because the injection of "quicksilver" would result in faster punches. (5) While neurologic or renal toxicity can occur, it is interesting that the majority of the patients described in the literature who have received IV mercury injections had relatively few toxicities despite sometimes massive doses (in one case, 20 mL elemental mercury (5)). Many of the short-term symptoms from IV injection can be attributed to pulmonary embolism and infarction from the mercury globules trapped in the pulmonary circulation. Chest pain, dyspnea, hypoxemia, and reversible pulmonary function defects are described. (5) Death secondary to pulmonary infarction from mercury has been reported. (6) Long-term, local tissue reactions to the mercury globules may lead to the formation of foreign-body granulomas. In experimental studies, miliary abscesses were found around mercury deposits in lung tissue in dogs, (1) and an autopsy report on a patient known to have received long-term IV mercury injections noted similar findings. (1)

The metallic densities seen on a chest radiograph often can persist for years, showing only gradual resolution. (7) Combined urinary, fecal, and expired air excretion of mercury is usually < 1 mg per day. Attempts at accelerated urinary excretion by the use of chelation agents can increase urinary rates threefold to fivefold. It is not clear that the use of these agents is warranted because of the extremely large doses achieved in IV injections and the relative paucity of toxic symptoms in many of these patients. (7) The slow biological oxidation of metallic mercury may result in the formation of soluble salts, which ultimately are excreted by the colon, kidney, and salivary glands. (7)

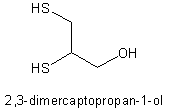

In our patient, it was difficult to differentiate between the symptoms of respiratory distress found in pneumococcal infection and those in IV mercury injection. The patient received oxygen, IV antibiotic therapy, and, initially, dimercaprol (during BAL) as a chelation agent. Dimercaptosuccinic acid was substituted as a chelation agent to reduce toxicity, and the patient's subsequent hospital course was notable for persistent fevers for 13 days, transient elevation in transaminase levels (possibly secondary to the dimercaptosuccinic acid therapy), and a Heinz body-positive hemolytic anemia secondary to glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. The only toxicity directly attributable to the mercury was gingival stomatitis and periodontitis, which developed over several days following the mercury injection.

REFERENCES

(1) Conrad ME, Sanford JP, Preston JA. Metallic mercury embolization: clinical and experimental. Arch Intern Med 1957; 100:59-65

(2) Agocs M. Case studies on environmental medicine: mercury toxicity. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health & Human Services, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 1992

(3) Buxton JT Jr, Hewitt JC, Gadsen RH, et al. Metallic mercury embolism: report of cases. JAMA 1965; 193:103-105

(4) Bates BA. Mercury. In: Haddad LM, ed. Clinical management of poisoning and drug overdose. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1998; 750-756

(5) Celli B, Khan MA. Mercury embolization of the lung. N Engl J Med 1976; 295:883-885

(6) Johnson HRM, Koumides O. Unusual case of mercury poisoning. Br Med J 1967; 1:340-341

(7) Ambre JJ, Welsh MJ, Svare CW. Intravenous elemental mercury injection: blood levels and excretion of mercury. Ann Intern Med 1997; 87:451-453

* From Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, Evanston, IL. Manuscript received March 28, 2001; revision accepted April 25, 2001.

Correspondence to: Daniel Ray MD, FCCP, Evanston Hospital, 2650 Ridge Ave, Evanston, IL 60201; e-mail: d-ray@nwu.edu

COPYRIGHT 2002 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group