HERE is some evidence that the psychotherapeutic process can be enhanced by the use of drugs that invite self-disclosure and self-exploration. Such drugs, called psychedelic (meaning "mind-manifesting") might help to fortify the therapeutic alliance and facilitate abreaction, catharsis, understanding, acceptance, and forgiveness. One drug that may prove uniquely valuable for these purposes is the psychedelic amphetamine MDMA.

The drug revolution that began 30 years ago has transformed psychiatry, but it has left little imprint on psychotherapeutic procedures themselves. We have used psychiatric drugs as an adjunct to psychotherapy, and psychotherapy as an adjunct to psychiatric drugs. But efforts to make use of drugs directly to enhance the process of psychotherapy--diagnosing the problem, enhancing the therapeutic alliance, facilitating the production of memories, fantasies, and insights--have been very limited. In preindustrial cultures, however, drugs were used to enhance a process of psychotherapeutic healing; and from 1950 to the mid-1960s, 15 years of experimentation took place in Europe and the United States--an episode in the history of psychiatry that is now almost forgotten. The drugs used in these therapeutic efforts were psychedelic or hallucinogenic substances, both natural and synthetic. It is now possible that this tradition might be revived by the use of new synthetic drugs that may have many of the virtues of the older psychedelics as enhancers of the psychotherapeutic process without most of their disadvantages.

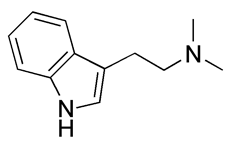

Psychedelics or hallucinogens are a large group of synthetic and natural drugs with a variety of chemical structures. The best known are mescaline, derived from the peyote cactus; psilocybin, found in over 100 species of mushrooms; and the synthetic drug lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which is chemically related to the lysergic acid amides, alkaloids that are found in morning glory seeds. This class of drugs also includes the natural substances harmine, harmaline, ibogaine, and dimethyltryptamine (DMT). Also widely used is ketamine, a synthetic drug that at high doses has been approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for use as a dissociative anesthetic but at lower doses can facilitate profound psychedelic experiences. There are also many synthetic drugs chemically described as tryptamines or methoxylated amphetamines. A few of these are diethyltryptamine (DET), 3,4,-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM). The most recent addition of interest to this list is 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA).

Ever since experimentation with psychedelic plants began, some users have maintained that the experience could be useful for self-exploration, religious insight, or relief of neurotic and somatic symptoms. The plants have been used for thousands of years in a number of cultures for healing and in magical and religious rites (Furst, 1976). A shaman or professional healer often conducts the rite. This religious and therapeutic use of psychedelic plants continues in the Amazon basin (with the psychedelic tea, ayahuasca), in western Africa (with the iboga root), in southwestern Mexico (where psychedelic mushrooms are used in healing rites), and in Native American church services in the western United States, which make use of the peyote cactus. The peyote ritual has been proposed as a possible adjunct to the treatment of alcoholism among American Indians (Albaugh and Anderson, 1974), and ibogaine has been used in therapeutic contexts for the treatment of opiate withdrawal and drug dependence (Mash et al., 2000).

Psychedelics were also used extensively in psychotherapy as experimental drugs in Europe and the United States for almost two decades. A large number of clinical papers and several dozen books on psychedelic drug therapy were published (Abramson, 1967; Debold and Leaf, 1967). They were employed for a wide variety of problems, including alcoholism, obsessional neurosis, and sociopathy (Shagass and Bittle, 1967; Savage, Jackson, and Terrill, 1962) and were also used to ease the process of dying (Grof et al., 1973). Complications and dangers were generally reported to be minimal (Cohen, 1960; Malleson, 1971). It soon became clear that with proper screening, preparation, and supervision, it was possible to minimize the danger of adverse reactions (Strassman, 1984).

Beginning in the early 1960s, as illicit use of LSD and other psychedelics drugs increased, it became difficult to obtain the drugs for psychiatric research or to get funding for such research, and professional interest declined. Those two decades of psychedelic research may some day be written off as a mistake that has only historical interest, but it might be wiser to see if something cannot be salvaged from them.

One reason for the therapeutic interest in psychedelic drugs was the belief of some experimental subjects that the experience reduced their feelings of guilt and made them less depressed and anxious and more self-accepting, tolerant, or sensually alert. Interest was also shown in making therapeutic use of the powerful psychedelic experiences of regression, abreaction, intense transference, and symbolic drama to improve or speed up psychodynamic psychotherapy. Two basic kinds of therapy emerged, one aimed at exploring the psychodynamic unconscious and the other making use of a mystical or conversion experience. The first type--psycholytic (literally, mind-loosening) therapy--required relatively small doses and several or even many sessions with LSD, mescaline, or psilocybin. It was used mainly for neurotic and psychosomatic disorders. Psychedelic therapy, the second type, involved the use of a large dose (200 micrograms of LSD or more) in a single session; it was thought to be potentially helpful in reforming alcoholics and criminals as well as improving the lives of normal people. In practice, many combinations, variations, and special applications with some of the features of both psycholytic and psychedelic therapy were adopted (Grinspoon and Bakalar, 1979: 194-8).

In psycholytic therapy, patients might be asked to concentrate on the interpretation of drug-induced visions, on symbolic psychodrama, on regression with the psychotherapist as a parent surrogate, or on discharge of tension and physical activity. Eyeshades, photographs, and other props were often used. Music played an important part in many forms of this therapy (Bonny and Savary, 1973). Patients usually remained intellectually alert and remembered the experience vividly. They also became acutely aware of ego defenses such as projection, denial, and displacement as they caught themselves in the act of using them.

Vignette One

The following example illustrates the treatment of neurotic depression and anxiety with psychedelic drugs. A 55-year-old man with a university education, good at his responsible job in a fairly large company, had a breakdown with symptoms of anxiety, neurotic depression, extreme lack of self-confidence, and sleeplessness. When LSD treatments started he had already been unfit for work and on a sick list for several months. He had 15 LSD treatments, first twice and then once a week, with doses up to 400 microgram.

In the fifteenth treatment, his growing anxiety reached a climax, with the feeling that he was "in a grip." He felt as if he were lying "curled up like a fetus" and then as if something was being done to his navel; suddenly he realized that he had been through the experience of being born. After this he felt that he was "through in a double sense of the word" and needed no further treatment.

The improvement was lasting. The patient was able to go back to work and claimed that he was a different person. For example, he was no longer irritated by small everyday matters as he once was, change so pronounced that for a long while his wife thought he was keeping strict control of himself all the time (Vanggard, 1964).

Vignette Two

In a book about her LSD treatment, a woman described the result as follows:

These passages were written three years after a five-month period during which the woman took LSD 23 times. Before that she had undergone four years of psychoanalysis, but she was convinced that the striking growth she experienced occurred during the five months of LSD therapy (Newland, 1962).

Such case histories can always be questioned as anecdotal. Placebo effects, spontaneous recovery, special and prolonged devotion by the therapist, and the therapist's and patient's biases in judging improvement must be considered. The most serious deficiencies in psychedelic drug studies were the absence of controls and inadequate follow-up; in addition, psychedelic drug effects are so striking that it is difficult to design a double-blind study. No form of psychotherapy for neurotics has ever been able to justify itself under stringent controls, and psychedelic drug therapy is no exception. Furthermore, psychiatrists never agreed about the details: for example, should the emphasis be on catharsis or on working through a transference attachment, and how much therapy is necessary in the intervals between psychedelic drug treatments? Because of the complexity of these drugs' effects, there are no simple answers to these questions. Although the treatments sometimes seemed to produce substantial improvement, no reliable formula for success could be derived from the results. In these respects, it is true, psychedelic drug therapy appears to be in no worse position than most other forms of psychotherapy.

During the relatively brief period of time during which psychedelic drugs were explored as therapeutic agents, they were found to have potential in a number of syndromes, including alcoholism. Psychedelic therapy for alcoholism was based on the assumption that one overwhelming experience could change the self-destructive drinking habits of a lifetime, and the hope that psychedelic drugs could produce such an experience.

Vignette 3

In one reported case, a 40-year-old black unskilled laborer was brought to a hospital from jail after drinking uncontrollably for 10 days. He had been an alcoholic for four years, and he was also severely anxious and depressed. He described his experience during an LSD session:

One week later his score for neurotic traits on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) had dropped from the 88th to the 10th percentile. Six months later his tests were within normal limits; he was still sober after 12 months (Kurland, 1967).

The question is whether the powerful effects of psychedelic drugs on alcoholics can be reliably translated into enduring change. Early studies reported dazzling success--up to 50 percent of severe chronic alcoholics recovered and were sober a year or two later (Hoffer, 1967). But later and better controlled studies were disappointing (Smart et al., 1984; Cheek, Osmond, Sarett, and Albahary, 1966). The problem is that many alcoholics improve, at least temporarily, after any treatment because excessive drinking is often sporadic and periodic relapses are common. An alcoholic who arrives at a clinic is probably at a low point in the cycle and has nowhere to go but up. But it would be wrong to suppose that a psychedelic experience could never be a turning point in the life of an alcoholic. As William James said, "Religiomania is the best cure for dipsomania." Unfortunately, these experiences have the same limitations as religious conversions. Their authentic emotional power is not a guarantee against backsliding when the old frustrations, limitations, and emotional distress have to be faced in everyday life. Even when the experience does seem to have lasting effects, it might have been merely a symptom of readiness to change rather than a cause of change.

Still, there is no proven treatment for alcoholism, and it may not make sense to give up entirely on anything that has possibilities. In the religious ceremonies of the Native American church, periodic use of medium to high doses of mescaline in the form of peyote is regarded as part of a treatment for alcoholism. Both the Native Americans themselves and outside researchers often contend that those who participate in the peyote ritual are more likely to abstain from alcohol. Peyote sustains the ritual and religious principles of the community of believers, and these sometimes confirm and support an individual commitment to give up alcohol. Another significant point is that controlled studies of psychedelic drug treatment of alcoholics indicate improvement lasting for several weeks to several months. If some way could be found to take psychotherapeutic advantage of this improvement, it might be helpful in the treatment of alcoholics. Recently, research in Russia using ketamine-assisted psychotherapy in the treatment of alcoholics has generated promising results (Krupitsky and Grinenko, 1997). Preliminary results of well-controlled research using ketamine in the treatment of heroin addicts have also been encouraging (Krupitsky, personal communication).

Psychedelic drugs have also been used to ease the pain, anxiety, and depression of the dying. Beginning in 1965, the experiment of providing a psychedelic experience for the dying was pursued at Spring Grove State Hospital in Maryland and later at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Institute. When patients received LSD or another psychedelic drug, dipropyltryptamine (DPT), after appropriate preparation, about one-third improved "dramatically," one-third improved "moderately," and one-third were unchanged according to the criteria of reduced tension, depression, pain, and fear of death (Grof et al., 1973; Pahnke, 1969). The drug session was designed as a part of a process of reconciliation--reconciliation with one's past, one's family, and one's human limitations. These studies employed no control groups, so it is not possible to separate with certainty the effects of the drug from those of the therapeutic arrangements that were part of the treatment. But the case histories reported in this work are impressive, and it would seem worthwhile to renew the research.

When a new kind of therapy is introduced, especially a new psychoactive drug, there is often a pattern of spectacular success and enormous enthusiasm followed by disillusionment. But the rise and decline of psychedelic drug therapy was somewhat unusual. From the 1960s on, the revolutionary pronouncements and religious fervor of the nonmedical advocates of psychedelic drugs began to evoke hostile incredulity rather than simply the natural skeptical response to extravagant claims backed mainly by intense subjective experiences. Twenty years after their introduction, psychedelics became pariah drugs, scorned by most psychiatrists and banned by the law.

A generation of physicians and scientists has grown up without the opportunity to pursue human research with psychedelic drugs, and the financial and administrative obstacles remain serious. These drugs should not be regarded as a panacea or as entirely worthless and extraordinarily dangerous. If the therapeutic results have been inconsistent, it is partly because of the complexity of psychedelic drug effects. For the same reason, we may not yet have had enough time to sort out the best uses of these drugs.

In two unusual pilot studies, psychedelic drug therapy is being explored in a pharmacotherapeutic context. The first study involves the administration of ketamine without psychotherapy to patients with major depression. Temporary symptom reduction was observed with the ketamine but not the placebo (Berman et al., 2000). At the University of Arizona in Tucson, the FDA has approved a small double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study in which researchers will administer psilocybin to 10 patients with chronic Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). The study is designed to investigate whether the physiological effects of one or two doses of psilocybin administered without psychotherapy will help to reduce symptoms of OCD temporarily, as has been suggested by several case studies (Delgado and Moreno, 1998). This study will mark the first time in over 25 years that psilocbyin will be given to a patient population in an FDA-approved clinical context.

Despite the two examples, it is a fundamental misunderstanding to consider most psychedelic drug therapy a form of pharmacotherapy, which must be regarded in the same way as prescribing lithium or phenothiazines. The claims of psychedelic drug therapy are subject to the same doubts as those of psychodynamic and other forms of psychotherapy. The mixture of mystical and transcendental claims with therapeutic ones is another aspect of psychedelic drug therapy troubling to our culture. Preindustrial cultures that made use of psychedelic plants were willing to tolerate more ambiguity with regard to the psychedelic healing process as both religious and medical.

But attitudes may be changing. A growing literature on the ideas and techniques shared by primitive shamans, Eastern spiritual teachers, and modern psychiatrists is emerging. They remind us that the word "cure" means both treatment for disease and the care of souls, and that all psychotherapy relying on insight in some ways resembles a conversion. Our society still has not found a way to be at ease with psychedelic drugs, but the scientific and medical communities should eventually acknowledge their potential, devise new and better questions to ask, and give psychedelic research another chance.

We may now have an opportunity to revive research into the use of psychedelic drugs to enhance psychotherapy. Dozens of psychedelic drugs are known, some of them synthesized only in the last 30 years. Few have been tested thoroughly on human beings. Their effects are sometimes different from those of LSD and other familiar substances. These differences may be significant for the study of the human mind and for psychotherapy, but we need more controlled human research to analyze them. In particular, certain psychedelic drugs do not produce the same degree of perceptual change or emotional unpredictability as LSD (Naranjo, 1975; Yensen et al., 1976). Among these is MDMA, a relatively mild, short-acting drug that is said to provide a heightened capacity for introspection, intimacy, and empathy along with temporary freedom from anxiety, depression, and defensiveness without distracting changes in perception, body image, and the sense of self (Riedlinger, 1985; Seymour, 1985; Liester et al., 1992a, 1992b).

MDMA was first synthesized in 1912 and began to come into both therapeutic and nontherapeutic use in the United States and Europe in the late 1970s. What we know about it now is largely anecdotal, but enough has been written to give some confidence that the general nature of the psychotherapeutic experience can be accurately described. As compared with the more familiar psychedelic drugs, it evokes a gentler, more subtle, highly controllable experience that invites rather than compels intensification of feelings and self-exploration. The user is not forced onto any mental or emotional path that is frightening or even uncomfortable. One patient described it this way: "I felt that my cognitive powers were unaffected. That is, except on the few occasions where the affective experiences were very strong (a minute or two, it seemed, at most), I could guide my thoughts to and away from whatever areas I chose."

The drug is taken in doses of 75 to 175 mg by mouth; the effects begin 30 to 45 minutes after ingestion and last two to four hours (Vollenweider, Jones, and Baggott, 1998). The onset of action is accompanied by a rise in heart rate and blood pressure, dry mouth, loss of appetite (which may last for a day), and sometimes mild nausea, jaw clenching, or teeth grinding. Transient anxiety, occasional nystagmus, an urgent need to urinate, and fatigue for a day or two afterward are also occasionally reported. Bad trips, psychotic reactions, and flashbacks of the type produced by LSD and mescaline are reported extremely rarely, almost always when MDMA is taken in combination with other drags. Prolonged adverse reactions are apparently also very rare.

Most therapy users apparently do not want to repeat the experience often or treat it casually, mainly because of its emotional intensity. There are no reports of craving or withdrawal symptoms when MDMA is taken in a clinical context. With higher doses and more frequent use, tolerance to the desired effects develops and the physical side effects become more uncomfortable. A caution should be added, however. The very properties that suggest MDMA might be therapeutically useful--its capacity to diminish anxiety and depression and promote easy emotional communication--also create a danger of unconstructive use, just as the therapeutically useful capacity of opiates to reduce pain makes them subject to abuse.

A few psychiatrists in Switzerland legally used MDMA in hundreds of patients from 1988-1993, though no controlled scientific research was conducted with these patients (Gasser, 1994-1995). Some dedicated therapists in other parts of Europe and in the United States have illegally used MDMA as an aid to psychotherapy for more than two decades (Stolaroff, 1997). MDMA has now been taken in a therapeutic setting by thousands of people, apparently with few complications. At this time it is difficult to state precisely how MDMA may be helpful in any particular type of psychotherapy, but the characteristics of the experience suggest that it could be useful in catalyzing the psychotherapeutic process irrespective of the theoretical grounding of the particular psychotherapy. These characteristics should be of interest to Freudian, Rogerian, and existential humanist therapists.

MDMA is generally used once or at most a few times in the course of therapy. It is said to fortify the therapeutic alliance by inviting self-disclosure and enhancing trust. Some patients also report better mood, greater relaxation, heightened self-esteem, and other beneficial changes that last for several days to several weeks. Psychiatrists who have used MDMA suggest that it might be helpful, for example, in marital counseling and in diagnostic interviews, as well as in more traditional forms of psychotherapy. The reports of therapeutic results so far are anecdotal and unverified and require more systematic study for evaluation, but they are promising. MDMA carries little of the baggage that made it difficult to work with LSD in psychotherapy--the 8- to 12-hour duration of action, the possible loss of emotional control, the perceptual distortion, and the occasional adverse reactions and flashbacks.

Patients in MDMA-assisted therapy report that they lose defensive anxiety and feel more emotionally open, and that this makes it possible for them to get in touch with feelings and thoughts not ordinarily available to them. One patient described his experience as "primarily an intense warmth and security about myself and other people." He added, "MDMA breaks down inhibitions about communication, making it easy to give or receive criticism or compliments that under normal circumstances are embarrassing." Another patient put it this way: "I believe the most beneficial aspect of how I felt during the session was that I felt very little defensiveness. On my own and to myself during the session, I thought about things in myself that I didn't like. I was able to accomplish this without feeling guilty or defensive."

Another MDMA patient wrote, "One of the major `differences' [from a non-MDMA-assisted psychotherapy session] was the feeling of security and tranquility. I had the feeling of being safe. Nothing could threaten me. I briefly tried to fantasize natural catastrophes, like an earthquake. I did not feel anxious or threatened." This patient also suggested that the effects of MDMA-assisted therapy may endure. Eighteen months after her third and last MDMA session, when she was asked whether she thought there was a lasting benefit, she replied, "I have been able to experience myself more fully ... to feel my feelings ... to be totally with myself ... to experience the ease of expressing myself when I am in touch with myself. The sessions enabled me to break through my defenses (rationalizing, analyzing, intellectualizing, etc.) that I used to win approval of myself and others ... to break through my facade and to go to the truth underneath.... At various times [that truth] meant grief, love, sadness, fear, humor."

MDMA might also help in working through loss or trauma. One patient described the effect as follows: "After a [n] [MDMA-assisted therapy] session where I grieved the loss of [my boyfriend] in my life, it surprised me that I felt so good about myself for having grieved so deeply ... for having been so deeply into my real self, crying my heart out, and how healthy it felt to know that I had really been there for those feelings rather than the facade I was living with--trying to be strong and get on with my life and unconsciously to avoid the pain, disappointment and sadness ... as well as my fear of being alone."

Another patient said: "I think that I experienced a more solid adjustment to my father's death about a year previously and to the breakup of my engagement about three months previously. [During the session and since then they have] seemed to recede into the distant past, as if they had happened longer ago and I had less emotional attachment to them. This was helpful, as I feel less emotionally attached to those events, but have integrated them into my personal history."

MDMA is also said to help patients experience closeness and empathy. Nine months after his MDMA-assisted therapy session, a patient noticed "feelings of closeness and sharing with others--evaporation of the usual barriers to intimate communication." Another said, "I would say this is a heart drug, but not in the way I would have expected. I did not feel romantic love, strong feelings. I felt attention toward [the therapist and his co-therapist wife] and a concern for them and how they were. This feeling was one of compassion for their needs ... this feeling I have been able to carry over after the immediate MDMA effects have gone."

Many MDMA patients have claimed a lasting improvement in their capacity for communication with others. For example, one man who was asked about enduring effects five months after his sessions answered: "Communication is improved with [my wife], less defensiveness between us, more leeway for diversity, desires, etc."

Interest in and capacity for insight is also said to be enhanced. Five months after one MDMA-assisted therapy session a patient reported that "insights into problems have proved accurate and helpful in planning my private and personal life." Later he added, "I have a broader perspective on my life and activities; that carries on."

Many report heightened self-esteem. Two and one-half months after his MDMA-assisted therapy experience a man wrote: "A long-lasting effect is an enhancement of self-esteem. I really feel better about who I am and what I have to offer." A woman who had two MDMA-assisted therapy sessions wrote four and one-half months later: "I feel the sessions allowed me to experience my `higher centers'--I expanded my boundaries, grew in dimensions, and in general feel I have more awareness of what it is to be alive. I also literally got rid of a lot of negative material I carried around with me forever. This has resulted in more energy, a greater feeling of freedom and strength, deeper joy, less pain."

Many patients report strengthening of trust and increased capacity for intimacy. As one patient stated: "It [the MDMA experience] was characterized by warmth. Although I was intellectually lucid and clear, the chief impact of the experience for me was in the heart, and not in the head. Fundamentally it seemed to facilitate intimacy. I found I could give and receive at very intimate levels without embarrassment or defensiveness." Another patient said that "I found it to be uncanny how easy it was to speak freely ... about feelings. I'm generally not very good at that but the MDMA apparently enabled me to let down the defenses and open up the offenses--but all in a gentle, matter-of-fact sort of way." And still another observed: "It breaks down the walls--relieves inhibitions--free thoughts escape under a euphoric cloud that makes it okay to say anything and everything."

These features of the MDMA experience may account for the common observation that an MDMA-assisted therapy session can greatly enhance the therapeutic alliance. Many patients report how much more they trust the therapist and how much closer they feel to the therapist after one such session. If, as many believe (Moms and Strupp, 1982; Gomes-Schwartz, 1978), the strength of the therapeutic alliance is the best predictor of a good outcome in therapy, this characteristic of MDMA would be of general usefulness.

On May 31, 1985, the Drug Enforcement Administration invoked an emergency provision to place MDMA on Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. Because of this scheduling it has been impossible or exceedingly difficult to pursue any further clinical research. Almost all contemporary research is aimed at determining the parameters of MDMA's toxicity or its pharmacokinetics or mechanisms of action. The only government-approved scientific study in the world in which MDMA is being used in a patient population is a recently initiated Phase 1 dose-response study in Spain in patients with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the United States, a pilot study investigating the use of MDMA in the treatment of PTSD has been presented to the FDA for review.

The major concern expressed about MDMA is its potential neurotoxicity to serotonin nerve terminals (McCann et al., 1998). Whether any neurotoxicity occurs when therapeutic dose levels of MDMA are administered in controlled clinical settings is a topic of heated debate (Vollenweider, Gamma, Liechti, and Huber, 1999; McCann and Ricaurte, 2001). PET scans measuring serotonin transporter binding sites in MDMA-naive subjects given a single dose of MDMA from 1.5 to 1.7 mg/kg (within the therapeutic range) indicated no significant reductions. This suggests that either there were no reductions or they were too small to measure (Vollenweider, Jones, and Baggott, 2001). Even if there is some neurotoxicity from therapeutic doses, evidence for clinically significant functional or behavioral consequences from such doses is entirely lacking. No reductions occurred in psychological or neuropsychological measures, cerebral blood flow, or brain wave activity (EEG/ERG) in a cohort of MDMA-naive subjects administered a single dose of MDMA (Vollenweider, Jones, and Baggott, 2001). As with all drugs, the challenge is to balance risks and benefits. Given the present state of knowledge, the risk to patients from participating in MDMA research has been considered by regulatory agencies and impartial experts to be within the acceptable range (Aghajanian and Lieberman, 2001).

Whether or not MDMA fulfills its promise, other drugs may be developed that are useful in psychotherapy. It would be an error to put too many obstacles in the way of human research aimed at understanding the therapeutic potential of such drugs. The fundamental aim here is not pharmacotherapy, and the drugs are not primarily symptom-relievers but catalysts. Like psychotherapy, they depend for their usefulness on the sensitivity and talent of the therapist who employs them. To ignore the possibility of reviving the centuries-old but now neglected tradition of drug-enhanced psychotherapeutic healing would mean unnecessarily limiting the potential of psychotherapy itself to help people gain insight into their problems and bring more perspective to their lives.

* The authors wish to express their indebtedness to George Greer, M.D., for generously sharing his clinical experience with us.

References

Abramson, H. A., ed. The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism. New York: Bobbs- Merrill, 1967.

Aghajanian, G., and J. Lieberman. "Response." Neuropsychopharmacology 24:3 (2001): 335-336.

Albaugh, B. J., and P. O. Anderson. "Peyote in the Treatment of Alcoholism among American Indians." American Journal of Psychiatry 131 (1974): 1247-51.

Berman, R. M., et al. "Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine in Depressed Patients." Biological Psychiatry 47:4 (Feb. 15, 2000): 351-4.

Bonny, H., and L. Savary. Music and Your Mind: Listening with a New Consciousness. New York: Harper and Row, 1973.

Cheek, F. E., H. Osmond, M. Sarett, and R. S. Albahary. "Observations Regarding the Use of LSD-25 in the Treatment of Alcoholism." Journal of Psychopharmacology 1 (1966): 56-74.

Cohen, S. "Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. Side Effects and Complications." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 130 (1960): 30-40.

DeBold, R. C., and Russell C. Leaf, eds. LSD, Man, and Society. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1967.

Delgado, P. L., and F. A. Moreno. "Hallucinogens, serotonin and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder." Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 30:4 (Oct.-Dec.,1998): 359-66.

Furst, P. T. Hallucinogens and Culture. San Francisco: Chandler and Sharp, 1976.

Gasser, P. "Psycholytic Therapy with MDMA and LSD in Switzerland: Follow-up Study on the Results of Swiss Research Conducted during 1988-1993." Bulletin of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies 5:3 (Winter, 1994-1995): 3-7.

Gomes-Schwartz, B. "Effective Ingredients in Psychotherapy: Prediction of Outcome from Process Variables." Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 46 (1978): 1023-35.

Grinspoon, L., and J. B. Bakalar. Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered. New York: Basic Books, 1979.

Grof, S., et al. "LSD-assisted Psychotherapy in Patients with Terminal Cancer." International Pharmacopsychiatry 8 (1973): 129-41.

Hoffer, A. "A Program for the Treatment of Alcoholism: LSD, Malvaria, and Nicotinic Acid." The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism. Ed. H. Abramson. New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967: 353-402.

Krupitsky, E. M., and A. Y. Grinenko. "Ketamine Psychedelic Therapy (KPT): A Review of the Results of Ten Years of Research. "Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 29:2 (Apr-Jun, 1997): 165-83.

Kurland, A. A. "The Therapeutic Potential of LSD in Medicine." DeBold and Leaf (1967): 20-35.

Liester, M. B., et al. "Phenomenology and Sequelae of 3,4-methylene-dioxymethamphetamine Use." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:6 (June 1, 1992a): 345-52; discussion, 353-4.

--. "Discussion." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:6 (June 1, 1992b): 353-4.

Malleson, N. "Acute Adverse Reactions to LSD in Clinical and Experimental Use in the United Kingdom." British Journal of Psychiatry 118 (1971): 229-230.

Mash, D. C., et al. "Ibogaine: Complex Pharmacokinetics, Concerns for Safety, and Preliminary Efficacy." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences--Neurobiological Mechanisms of Drugs of Abuse. 94 (2000): 394-401.

McCann, U. D., et al. "Positron Emission Tomographic Evidence of Toxic Effect of MDMA ("Ecstasy") on Brain Serotonin Neurons in Human Beings." Lancet 352:9138 (Oct 31, 1998): 1433-7.

McCann, U., and G. Ricaurte. "Caveat Emptor: Editors Beware." Neuropsychopharmacology 24:3 (2001): 333-334.

Moras, K., and H. H. Strupp. "Pretherapy Interpersonal Relations, Patient's Alliance, and Outcome in Brief Therapy." Archives of General Psychiatry 39 (April 1982): 405-9.

Naranjo, C. The Healing Journey. New York: Ballantine Books, 1975 [1973].

Newland, C. A. Myself and I. New York: American Library, 1962.

Pahnke, W. N. "The Psychedelic Mystical Experience in the Human Encounter with Death." Harvard Theological Review 62 (1969): 1-21.

Riedlinger, J. E. "The Scheduling of MDMA: A Pharmacist's Perspective" Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 17 (1985): 167-71.

Savage, C., D. Jackson, and J. Terrill. "LSD, Transcendence, and the New Beginning." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 135 (1962): 425-39.

Seymour, R. B. "MDMA: Another View of Ecstasy." Pharm Chem Newsletter 14 (1985): 1-5.

Shagass, C., and R. M. Bittle. "Therapeutic Effects of LSD: A Follow-up Study." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 144 (1967): 471-78.

Smart, R. G., et al. "A Controlled Study of Lysergide in the Treatment of Alcoholism." Quarterly Journal of Studies in Alcoholism 27 (1984): 469-482.

Stolaroff, M. The Secret Chief. Charlotte, N.C.: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, 1997.

Strassman, R. J. "Adverse Reactions to Psychedelic Drugs: A Review of the Literature." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 172 (1984): 577-95.

Vanggard, T. "Indications and Counterindications for LSD Treatment." Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 40 (1964): 427-37.

Vollenweider, F. X., A. Gamma, M. Liechti, and T. Huber. "Psychological and Cardiovascular Effects and Short-term Sequelae of MDMA ("Ecstasy") in MDMA-naive Healthy Volunteers." Neuropsychopharmacology 4 (Oct. 19, 1998): 241-51.

--. "Is a Single Dose of MDMA Harmless?" Neuropsychopharmacology 21:4 (Oct. 1999): 598-600.

Vollenweider, F., R. Jones, and M. Baggott. "Caveat Emptor: Editors Beware." Neuropsychopharmacology 24:4 (2001): 461-463.

Yensen, R., et al. "MDA-assisted Psychotherapy with Neurotic Outpatients: A Pilot Study." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 163 (1976): 233-45.

Richard E. Doblin is founder and president of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. His publications include "Leary's Concord Prison Experiment: A 34-Year Follow-up Study" in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs (1998).

COPYRIGHT 2001 New School for Social Research

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group