"Standing on bare ground--my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space--all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; I am part and parcel of God."

"I was unprepared for what happened. Almost instantly, I somehow knew that I had opened a door into something unknown but very powerful. I remember uttering a curse. My field of vision was immediately a dark ink-black, which then rapidly filled with brightly colored swirling phosphorescent 'sparkles.' This vortex built in intensity ... and luminosity until it coalesced into a sort of ball of intense light into which I was swallowed up. This light or energy was completely overwhelming; it roared like a tornado ... like being at the center of a nuclear explosion without being consumed with pain or annihilated. I felt This is God, and for the first time, I could sense the power that this Creative Force actually represented. I was totally in awe. Yet throughout the whole experience, I was not able to keep a grasp on my own personality. I was just a thread of freely running consciousness, holding on for dear life to this screaming freight train of energy that was tearing through the cosmos. At the same time, I had the realization that this light was God; my body was filled with a feeling of ecstasy of love."

"I--my drashta, the Looker--became separated from my body and mind. This was Atman ... And then the Looker witnessed everything in the world, this ground, these trees, this river, this mountain, and all people, and all other things, the light, the energy, and also itself, myself--all were Shakti, the primordial energy of the universe. There was no Seer and seen, no Looker and looked--they are One--that is Brahman, the Absolute."

Three accounts of religious ecstasy with incredible similarities. Yet their authors were separated by centuries and cultures. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote the first report, an account of his experience in a New England wood in his 1836 essay Nature. The second comes from a neuropharmacologist and professor at a large American university who recently experimented on himself using extract from a psychoactive plant. The third is a description by a Hindu yogi about his own practices.

To these we could add testimony by schizophrenics about their hallucinations of becoming God, reports by shamans of their out-of-body experiences, accounts of Dionysian rituals in ancient Greece, and quotations from poets and visionaries like William Blake and the Biblical prophets. But all describe a similar clinical picture: The body is disabled by paroxysms of ecstasy. Normal judgment is, to say the least, suspended. Surrounding objects are obscured by frank hallucinations of vortexes and floodlights, or else they're transformed by luminous halos and revelatory detail. Voices from elsewhere are heard dictating instructions or secret messages. Then, there's that painful sense of the meaningfulness of everything. Seized by the immanent symbolism in the world, the subject reports talking to, seeing, or becoming God.

Being capable of such visions is hardly an adaptive skill. God-talking animals, even intelligent bipedal ones, probably wouldn't last long in the jungle. You wouldn't want to defend yourself from a predator--or even drive a car for that matter--while in a state of religious ecstasy. So why do humans have this remarkable--and, from the point of view of brute survival, seemingly irrelevant--facility for communicating with the gods? What part of the brain perceives transcendence? Was Emerson describing something that really happened to his soul, or was he only the victim of a conspiracy of neurochemical accidents in his brain? Does hathayoga open hailing frequencies between the mind and the universal spirit, Shakti, or does it simply activate a part of the brain that tricks people into feeling transcendent? Are these events an epiphenomenon of the sheer complexity of the brain, or are they gateways to a new kind of knowledge?

In order to find research which sheds light on these questions, we have to take a journey into the margins of science, a wild zone straddling institutionally sanctioned research, illegal drugs, and metaphysics. Most scientists won't speak freely about metaphysical matters, at least out of church. And to make matters worse, the most potent tools for exploring how the brain goes ecstatic are also ones that come loaded with social, political, and ethical baggage: LSD, PCP, mescaline, psilocybin, and Ecstasy. You can't just feed these psychoactive substances to humans and expect to get funded by legitimate agencies, given the prevailing attitudes toward such exotic compounds.

As a result, using psychedelic chemicals as a scientific route to the inner universe is just a tenuous little footpath in the thickets of social disapproval and institutionalized skepticism. Nonetheless, science has offered a few clues to how it is the human brain achieves transcedent or altered states.

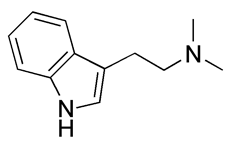

The National Institute on Drug Abuse has opened the door to such research, if only a crack. For the first time in more than 20 years, with the permission of the FDA and the DEA, they have given a federal grant to study the effect on humans of an hallucinogen listed on Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. Rick Strassman, a psychiatrist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, has received both permission and support to study DMT (dimethyltryptamine), a relatively obscure but very potent hallucinogen first discovered in a plant used for snuff by Amazonian natives.

Gathering most of his subjects--experienced hallucinogen users, three-fourths of them men--via word of mouth through the drug underground, Strassman injects them with DMT intravenously, watches them closely through the swift and often intense experience, and then keeps close tabs on them for months after the experiment. As DMT is working, Strassman measures physiological responses like heart rate, blood pressure, vital signs, and core body temperature, and takes blood samples to measure the levels of brain-related hormones and DMT. "The most striking thing about DMT," says Strassman, "is its rapid onset. Sometimes, even before infusion is complete, subjects begin experiencing hallucinations and lose consciousness of their physical bodies. Peak effects can occur within about sixty seconds."

DMT produces striking psychedelic effects: intensely colored kaleidoscopic displays of visual imagery, three-dimensional and bright. Subjects experience a separation of consciousness from their physical bodies and then extreme emotional states--euphoria, terror, panic, bliss. "It's a short-lived experience, and even if it's horrible, which it is in some cases, it's short and horrible." Of course, Strassman takes pains to weed out subjects with psychological disorders or physical problems that might jeopardize their well-being, and as a trained clinical psychiatrist with a nurse on hand, he helps people get through the most difficult parts of their DMT trips.

Soon after the most potent effects of the drug wear off, Strassman also administers a long questionnaire--one version contains 230 questions--aimed at discovering the psychological and subjective effects of DMT. And one of those subjective effects, unavoidably, seems to be a trend to see God or experience transcendence. In his preliminary interviews with experienced users of DMT, he found many who reported spiritual experiences. So in designing his questionnaire, Strassman included questions that reflected this recurring theme. For instance, Question #31 ]Did you feel[ awe and amazement? Question #33: ]Did you feel[ the presence of a higher power, god, or spirit? Question #43: ]Did you feel[ oneness with the universe? Question #45: ]Did you feel[ reborn? "To leave those out would be ignoring one of the reasons people take hallucinogens."

And, in fact, the questions get statistically strong responses. "Actually," says Strassman, "about one-quarter to one-third have experiences that could be interpreted as transcendent or religious or having something to do with their concept of God."

These results leave no doubt that as much as any other drug or stimulation, DMT has the potential to induce religious ecstasy. But what is the meaning of that experience? Is it real in any sense or just an artificially induced hallucination? As Strassman points out, DMT is already present in the human body, begging us to wonder if there isn't some purpose to these perceptions that come on so strong when the chemical is administered in potent doses. What is DMT and the potential experiences it can induce doing inside of us in the first place?

Physiologists have traced the route of psychoactive drugs like DMT and LSD-25 through the anatomy of the brain, matching the presence of these chemicals with known functions of different regions. But a trip to the various neighborhoods of the brain involved in religious ecstasy is a little like touring an empty Hollywood set. In order to understand the real drama, you have to see the actors at work.

Most psychoactive drugs like DMT script a radical alteration in the role of the major player in the brain's activity, serotonin--5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5-HT for short. Serotonin is a universal operator, the Mr. Big of neurotransmitters, with fingers in the pie of almost every processing transaction in every territory of the brain. Michele Spoont of the department of psychiatry at the Ramsey Medical Center in St. Paul, Minnesota, suggests that serotonin's main function is to regulate the flow of information through the neural system. It neither inhibits nor promotes neural communication so much as it keeps a balance, ensuring that the whole system stays within normal limits. It's even possible to speculate that this normal situation, this homeostatic, self-regulating system, somehow translates into our sense of normal reality, our "sense of balance." Serotonin is the gyroscope of the mind-brain. Increasing or seriously depleting serotonin in the brain seems to destabilize this homeostatic control, loosening our grip on what we are accustomed to viewing as reality.

Such a model of serotonin's action supports the view of many proponents of hallucinogenic drugs--like Timothy Leary, who has maintained for a long time that LSD and MDMA don't so much do something to us as they permit us to experience a potential that already exists in the brain, a potential that is dampened or blocked by ordinary experience. In order to transcend, you have to kick the gyro, launching yourself on a trajectory skew to the plane of normal reality.

Serotonin's headquarters is a complex of closely associated central bodies buried deep in the brain stem, above where the brain meets the spinal cord, called the raphe nuclei. Of these, the dorsal and median raphe nuclei produce 80 percent of all serotonin as well as send out messages to other parts of the brain, acting somewhat like a central switchboard.

Another potent hallucinogenic drug associated with transforming experience is MDMA--3, 4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine, or as it's aptly known on the streets, Ecstasy (and sometimes "Adam," a scramble of its chemical acronym). Studies of Ecsatsy in rats show that the drug works by acting as an agonist--a releaser--of serotonin in the dorsal raphe nucleus, stimulating wildly increased production. And it would be tempting to see that deep structure, radiating messages from the most primitive part of the brain, as the one responsible for ecstatic visions. But it's not that simple.

The dorsal raphe nucleus is like the timer in the engine or the clock in a computer, but it's doubtful that it does any of the cognitive processing itself. From the raphe nuclei, serotonin floods down nerve projections into other important areas of the brain like the limbic system. Even though many of the sensations that seem to arise from limbic areas have the feel of something primordial and unworldly, the term limbic comes not from limbo, but from the Latic word for belt. It girdles some of the more primitive regions of the brain, the lateral forebrain where the amygdala, the basal ganglia, the hippocampus, and the entorhinal cortex are found.

Typical, normal perception works like this: Sensory input comes into the entorhinal area, goes into the hippocampus, returns to the enthorhinal, and then shuttles back to the motor cortices. The hippocampus stores memories. The amygdala and the temporal lobe apparently tie an emotion to a memory so that memory isn't just like a snapshot of someone elses's picnic; there's an emotional, personal component to it.

Say you want to move to the refrigerator for a snack. You get a good visual fix on the refrigerator, sending signals to the limbic structures which remember, Aha. A refrigerator. Foods's in there! Your limbic region acts in a feedback loop with the environment. You may even summon memories of the smell and taste of those foods you haven't yet seen. The messages now cycle around from the limbic region to the motor cortex and feed back directions to your muscles--Walk toward the refrigerator--which brings you closer, giving new input to the limbic areas, where the brain now recognizes the handle to the refrigerator door--Mmm, good! We're getting closer.

But when you take a potent hallucinogen, you stimulate the serotonin receptors which are normally the targets for these neurons from the raphe nuclei, disrupting the brain's delicate balancing act in cycling normal input messages from the exterior world--adding special effects, you might say, to that snapshot. Your brain now sees, and seizes upon, not the vision of a mere refrigerator handle, but a divine, even alien "something different" suggested by the shape of the handle. Or perhaps the brain is now open to messages from a wholly different order of input, and you become blind to the refrigerator altogether.

At the same time, the messages out to the motor cortex of the brain are disrupted by the same flood of hallucinogen molecules, bombarding key serotonin receptors and sending signals unprovoked by an external stimulus. You experience a strange physical passivity to the point that you don't even feel connected to your body anymore. Your mind floats free, enjoying (or being overwhelmed by) images that no longer come from the physical world alone but from an "elsewhere," a new origin outside normal reality. Your motivation to open the refrigerator door may go down while your brain feeds hungrily on this new sort of input coming from someplace new. It's easy to see why you would feel that the messages originate with a divine source, since they aren't connected to normal reality and can't be correlated to the environment your senses tell you is there.

But these perceptions would be a jumble of snapshots in a shoebox were it not for the involvement of the higher organizing functions of the brain. Serotonin and the hallucinogens that act as serotonin agonists--like LSD, mescaline, DMT, and psilocybin--also travel to the thalamus, a relay station for all sensory data that are heading for the cortex. There, conscious rationalizings, philosophizings, and interpretations of imagery occur. The cortex of the brain now attaches meaning to the visions that bubble up from the limbic lobe--of burning bushes or feelings of floating union with nature. The flow of images is scripted and edited into a whole new kind of show, except the more evolved centers of the brain are now not only being pressed to deal with this alien input, but are also being stimulated with the flood of hallucinogen molecules, which stimulate serotonin receptors in the neocortex and disrupt its ability to carry out normal functions. So the neocortex is more liable to attach transcendent or alien significance, to the otherworldly perceptions transmitted from the nether regions of the brain. And the result is very likely to be a new way of thinking, new insights, conversion experiences.

David Nichols, professor of medicinal chemistry and pharmacology at Purdue University, speculates that what makes drugs like LSD so potent is that they act in many places at once, and these actions somehow "sum to give the net effect. If you're talking about a union with mystical oneness," says Nichols, "it may seem like there's not a whole lot of thought involved. It's more like a suspension of rational inspection, so you wouldn't expect a heavy involvement of the neocortex. On the other hand, when we look at chemicals that work to give some people these experiences, you find traces of the drug working throughout the cortex."

In short, by following the action of serotonin through the brain, it becomes clear that the whole concept of locating some mythical "transcendent receptor site" in the brain is too simplistic, even though such an atomistic approach currently dominates neuroscience research, according to Walter Freeman, a leading neurophysiologist. "Perception cannot be understood solely by examining properties of individual neurons," Freeman says. A professor of molecular and cell biology at Berkely, Freeman has argued in his experimental and biological work for a more macroscopic or holistic view of how the brain moves from sensory input to conscious perception. Even when we have simple cognitive experiences, he suggests, like sniffing a rose or recognizing a friend's face, the brain mobilizes large battalions of neurons scattered over vast regions of the brain. What the mind recognizes as a conscious event (Oh, that's a rose!) is the result of a coherent leaping into a new order of self-organizing complexity.

If Freeman is right, and that's what happens when we merely recognize the smile of Michelle Pfeiffer, imagine the much more complex events that must occur in the brain when your mind is caught in a cosmic whirlwind of transcendent meanings and images. We're still a long way off from understanding how the brain moves from a series of neurochemical events to massively subjective mental experiences like these.

"Connecting brain activities to subjective experiences is the Holy Grail of brain research," says Freeman. "But like the Holy Grail, such a complete view doesn't exist except as an ideal. You certainly can't think about such experiences as deriving from a 'place in the brain.' They're not a 'whereness.' You can fool yourself into thinking you've found the place where these experiences originate, but it's like pulling a spark plug in a car. The car stops working, but it's not the spark plug that made the car go in the first place."

Nichols agrees, even down to the metaphor. "What makes a car go? It is the ignition? The fuel in the cylinders? The wheels?" Nichols even suggests that some of these drugs, under the right circumstances, "reboot the system," changing or resetting the whole chemistry of the brain. Indeed, a few people who have ecstatic experiences also undergo a conversion of the soul, a profound reordering of their entire mode of perceiving and relating to the world. To extend Freeman's quip, it's not a whereness; it's a different kind of awareness. That's why many researchers into psychotropic drugs like Nichols see benefits for treating mental illness. "These drugs from an important therapeutic category that we're missing the boat on as a society."

Despite the out-of-body feeling that's so large and frequent a component of religious ecstasy, there may even be physical involvement in these experiences. Alexander Shulgin, the researcher who suggests this, works even farther out in the wilderness of deinstitutionalized science. Now a youthful 68 years old and with something of the mad scientist about him, Shulgin is the reigning godfather of psychotropic chemistry. Though he teaches a course in forensic pharmacology at Berkeley, his lab isn't to be found in any academic institution, but rather in a wildcat, oneman operation--government licensed--on a farm outside San Francisco. There, Shulgin brews one compound after another, tests them on humans--a small, reliable group of willing friends--and records his results. He recently published his decades of research in a thousand-page novel-cum-handbook for psychoactive drug aficionados, PIHKAL. The title isn't the code name for a powerful new substance, but a bit of whimsy: It stands for "Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved." (Phenethylamine is the basic molecule propelling many psychoactive compounds.)

In one experiment, Shulgin took the skeleton of an amphetamine molecule that contained bromine--DOB (2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine) a long-acting psychedelic--and tried to follow its route through the body and brain by using a man-made bromine isotope that was radioactive. "I like this approach with DOB and its cousin DOI [which has an iodine atom in place of the bromine] because other chemicals require sticking something artificial on them. But with DOB and DOI, the heavy elements that can be the gamma emitters are intrinsic to the chemical." It meant getting a cyclotron to generate the isotopes and a PET scanner to track the chemical through the brain and body. "I was able to bootleg positron-emission equipment because of work I did with the Lawrence Radiation Lab [in Berkeley]. But it also meant getting time on their cyclotron. Ever try to power up a cyclotron on the sly?"

Shulgin found that DOB went to the lungs, bladder, and the liver, where it was probably metabolized and transformed into something else before returning to the brain to do its mind work. So even the holographic, complex model of the brain suggested by Nichols, Strassman, and Freeman requires an additional complication: It may not be the drug itself, but some byproduct, a metabolite of the drug, that's reaching the brain to do its work. In short, the body is involved, too. "Every time you pare your toenails," Shulgin quips, "you may be throwing away cells intrinsic to the soul."

What inspires Shulgin to make this whimsical leap are reports like the following from one of his subjects on mescaline, recorded in PIHKAL: "I began to become aware of a point, a brilliant white light that seemed to be where God was entering, and it was inconceivably wonderful to perceive it and to be close to it. One wished for it to approach with all one's heart. I could see that people would sit and meditate for hours on end just in the hope that this little bit of light would contact them. I begged for it to continue ... but it faded away. ... The world was so far away from God, and nothing was more important than getting back in touch with Him. ... I ended up the experience in a very peaceful space, feeling that though I had been through a lot, I had accomplished a great deal. I felt wonderful, free and clear."

Without the props of big science, the large lab, the research assistants, and government funding, the explanation for why certain chemicals produce these intriguing reports remains tantalizingly out of Shulgin's reach. Even were he to get a big project, Shulgin wonders what it would lead to. "There's never enough to tell you what's going on neurochemically that translates into particular subjective experiences. What makes a subject say, 'I'm seeing God'? I doubt we'll ever know that just based on neurochemistry."

But there is a promising development in this story. Encouraged by success in getting federal funding, Strassman along with Nichols and other psychopharmacologists and M.D.'s plan to launch an independent research facility. Named the Heffter Research Institute after the German pharmacologist who discovered in 1897 that mescaline was the active chemical in the peyote cactus, it will be devoted to investigations of the effects, mechanisms of action, and medicinal value of hallucinogens, using strict scientific methods.

In 1793, the poet William Blake wrote, "If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite." Do these psychoactive drugs cleanse the doors of perception, or do they poison the mind, tricking it into delusions of the infinite and profound? It's chastening to note that many autobiographical accounts of severe mental breakdown (as those collected in a volume published in 1964 by Bert Kaplan, The Inner World of Mental Illness) begin with ecstatic or revelatory episodes which then grow increasingly and dreadfully psychotic and frightening. And it's also sobering that the activity of serotonin uptake in the brains of schizophrenics appears to echo the action of DMT, LSD, mescaline, PCP (phencyclidine), and other hallucinogens. As a final warning, many of the antipsychotic drugs are antagonists (suppressors) of serotonin activity. In other words, the chemicals that help control some of the more painful schizophrenic symptoms are the opposites of hallucinogens. Yet, whether poisons or mind expanders, it's obvious that psychotropic drugs get the human brain and perhaps the body, too, to undergo a massive and global change, and ecological shift for which, inexplicably and irrationally, the brain seems to be ready.

But reports of such experiences provoke big questions science doesn't have adequate answers for. Science seems reluctant even to pose them, tainted as they are with metaphysics. Why are humans endowed with a neurochemical ability, one might even say an imperative, to communicate with a universe of spirits in the first place? Why does this hallucinatory doorway to the gods lurk in the brain at all? Whether the mind, under these special serotonin-driven conditions, is listening to itself or is tuned to something that's really broadcasting from "out there" is a question that awaits a more metaphysically inquisitive science.

COPYRIGHT 1993 Omni Publications International Ltd.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group