Since the introduction of hydrocortisone in the early 1950s, topical corticosteroids have become the mainstay of treatment of many inflammatory dermatoses. The number of dermatologic steroids with increasing potency has proliferated. In recent years, three superpotent corticosteroids, namely, betamethasone dipropionate in optimized vehicle (Diprolene), clobetasol propionate (Ternovate) and diflorasone diacetate (Psorcon), have been added to the list. These steroids are classified as group I in Stoughton and Cornell's ranking of topical corticosteroids and are considered the most potent topical steroids available for clinical use.

Clinical trials have found these three agents to be highly effective, with an enhanced therapeutic response not seen with less potent corticosteroids. However, with this increased potency has come the problem of systemic and local side effects. Physicians must weigh the potential benefits against the adverse effects of superpotent steroids. This article delineates an effective and safe approach for the use of superpotent topical steroids.

History

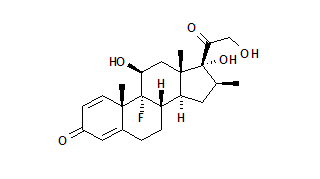

The molecular structures of various topical corticosteroids are given in Figure 1 [omitted].

Sulzberger and Witten' were the first physicians to use topical hydrocortisone for mild eczema. The introduction of 16 alpha hydroxylation and 9 alpha fluorination produced triamcinolone acetonide (Aristocort, Kenalog, Triacet, etc.) and resulted in a 40-fold increase in potency. (2,3) It was also found that application of plastic wrap occlusion would hydrate the stratum corneum, increasing the surface area of the skin by almost 40 percent and effecting a 100-fold increase in the efficacy of the drug. (4)

McKenzie and Stoughton (5) developed an assay to measure the ability of topical steroids to produce vasoconstriction. This test, which is known as the vasoconstrictor assay, relies on the fact that areas of blanching develop when a corticosteroid is applied to the skin. In general, the greater the degree of blanching, the more potent the drug.

In the mid-1960s, the addition of a methyl group on the 16 position made the molecule more soluble for penetration of the skin. This new steroid, betamethasone valerate (Betatrex, Beta-Val, Valisone, etc.), was found to have three times the vasoconstricting potency of fluocinolone acetonide (Fluonid, Flurosyn, Synalar, etc.). The development of betamethasone valerate provided a major breakthrough in the treatment of psoriasis and eczema. (3)

The first of the superpotent topical steroids, clobetasol propionate, became available in Europe in 1974. This agent was developed by the addition of a propionate base at the C17 position, a beta-methyl group at C16 and halogenation at the C21 position. Betamethasone dipropionate in optimized vehicle, which became available in 1985, is produced by esterifying the 17 and 21 hydroxyl groups of betamethasone and then optimizing the steroid in propylene glycol. First available in 1987, diflorasone diacetate is produced by the methylation of C16 and acetylation of C17 and C21. According to the vasoconstrictor assay, clobetasol propionate and betamethasone dipropionate in optimized vehicle are over 1,000 times as active as hydrocortisone. (6)

Efficacy

Topical steroids have four main effects on the skin: anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressant, antimitotic and vasoconstrictive. The anti-inflammatory properties are best manifested in the treatment of acute and chronic dermatoses, acute sunburn and arthropod bites. The immunosuppressive effect is exemplified in the treatment of discoid lupus erythematosus and lichen planus. The benefits of these drugs in the treatment of psoriasis may relate to the combination of anti-inflammatory and antimitotic activity. The vasoconstrictor effect of topical steroids has limited clinical application. (3)

Side Effects

LOCAL CUTANEOUS SIDE EFFECTS

All of the side effects reported with the less potent topical steroids may be accentuated with superpotent steroids.

Atrophy. Thinning of the epidermis and dermis produces transparency of the skin, resulting in telangiectasia, striae and purpura. Atrophic changes are most apparent at flexural sites. The skin can become very fragile, tearing and bruising easily ("steroid purpura"). (3) Such fragility is caused by rupture of the atrophic collagen fibers in the dermis with loss of support of the vessels. (6)

Preatrophy is the term used to describe covert vascular alterations of the skin, which can develop during the first two weeks of treatment with a superpotent topical steroid in patients with psoriasis. Preatrophy is visible using x 8 magnification and is qualitatively similar to the changes that are apparent in steroid-induced skin atrophy. The term preatrophy is used because these changes fade away or diminish after cessation of therapy, implying that the alterations are mostly reversible. (7)

Steroid Acne. The use of topical steroids for more than one month may either aggravate existing acne or induce steroid acne. (6) These lesions present as inflammatory red papules or pustules centering on hair follicles on the upper arm and upper trunk.

Perioral Dermatitis. This condition occurs predominantly in young women and presents as scaly erythema, papules and pustules in the perioral region, with sparing of the vermilion border Figure 4).

Steroid Rosacea. The application of a potent topical steroid can exacerbate preexisting rosacea. Papules, pustules, erythema and telangiectasia may develop on the forehead, cheeks and nose. (8)

Hypopigmentation. The use of topical steroids for longer than one month may result in loss of pigmentation. The hypopigmented areas may repigment one to two months after steroid therapy is discontinued. (6)

Hypertrichosis. Chronic use of steroids can lead to an overgrowth of body and facial hair. (9)

Superinfection. Topical steroids may lead to superinfection, including staphylococcal folliculitis, dermatophytosis (10) and candidiasis, (3) particularly when they are applied to flexural sites or used with polyethylene occlusion. When a fungal infection is treated with topical steroids, widespread and unusual clinical patterns may develop.

Infantile Gluteal Granuloma. The use of potent topical steroids in infants with diaper dermatitis produces violaceous red nodules when these agents are applied under occlusive plastic pants. Although the lesions resolve after cessation of therapy, atrophic scars often remain. (3)

Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Alani and Alani (11) have reported a 0.3 percent incidence of sensitivity to topical steroids. Cox (12) has described five cases of contact allergy to clobetasol propionate. Positive epicutaneous tests confirmed that the reactions resulted from the active steroid and not the preservatives.

SYSTEMIC SIDE EFFECTS

Percutaneous absorption of topical steroids in sufficient quantities can cause either suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis or the development of Cushing's syndrome. Systemic absorption is enhanced under the following circumstances: when large areas of the body are covered with steroid preparations (especially in children, since they have a large skin-surface-area-to-body-weight ratio); when the natural skin barrier is broken, as in psoriasis and dermatitis; when steroids are applied to scrotal skin or other moist intertriginous areas; when the treated area is occluded with polyethylene wrap, and when superpotent steroids are used. (13)

Clobetasol cream and ointment were found to produce HPA axis suppression in three of four patients treated with 3.5 g twice daily (49 g per week), in two of nine patients treated with 1.75 g twice daily (25 g per week), and in one of nine patients treated with only 1 g twice daily (14 g per week). In contrast, betamethasone dipropionate in optimized vehicle, in a dosage of 7 g daily (49 g per week), produced a minimal reduction of plasma cortisol and therefore resulted in less suppression of the HPA axis. (14) With diflorasone diacetate, HPA axis suppression was not observed in a limited number of patients treated with 15 g twice daily for seven days. (5)

Guidelines for Use

Superpotent topical steroids should not be used in children because of the increased ratio of skin surface area to body weight. Chronic use may adversely affect growth and development.

Elderly persons already have thinned skin, and superpotent topical steroids may greatly accentuate the changes that lead to further atrophy or purpura. In the elderly, drugs are cleared from the skin more slowly, with consequent potentiation of their effects. (3) Therefore, superpotent topical steroids should not be used for a prolonged period in this age group.

Use of superpotent topical steroids and fluorinated steroids on the face should be avoided, because of the potential for perioral dermatitis. Steroid folliculitis, telangiectasia and other overt signs of cutaneous atrophy can also occur.

Since flexural areas (e.g., axillae, groin, and popliteal and antecubital fossae) are natural sites of occlusion, these areas are particularly prone to develop steroid-induced atrophy. Therefore, superpotent steroids should not be used in these areas longer than two weeks. Similarly, superpotent topical steroids should not be used under polyethylene occlusion because enhanced absorption may lead to the development of atrophy and bacterial infection.

The degree of penetration of the steroid is directly related to the thickness and integrity of the stratum comeum. Penetration through the palms and soles is negligible. In other areas, it occurs in the following order of increasing penetration: the dorsa of the hands and feet, the lower arms and legs, the upper arms and legs, the chest and back, the face, the eyelids and scrotum, and the mucous membranes. Because of enhanced penetration in the latter four areas, superpotent topical steroids should not be used at these sites.

Superpotent topical steroids should be used only for moderate or severe steroidresponsive dermatoses. The dosage should not exceed 45 to 50 g per week. With Temovate Cream and Ointment and with Diprolene Cream and Lotion, a drug holiday of at least one week is required after 14 days of continuous use. Diprolene Ointment and Diprolene AF Cream (in an emollient base) and Psorcon Ointment do not require a rest period, although vigilance is necessary.

The treatment of psoriasis is an excellent example of the benefits of superpotent topical steroids. However, because of the potential for skin atrophy and HPA axis suppression, treatment must be of limited duration. Gammon and colleagues (16) reported success with an episodic regimen using up to three successive courses of clobetasol propionate twice a day for 14 days, separated by intervals of one to 19 weeks. However, 12 percent of patients had transiently low plasma cortisol levels in the morning.

Katz and associates (17) recently used betamethasone dipropionate in optimized vehicle in an intermittent pulse-dose regimen for extended maintenance treatment of psoriasis. Patients in the study initially received standard therapy for two to three weeks. Thereafter, the medication was used on weekends only; maintenance therapy consisted of three consecutive doses at 12-hour intervals, once weekly. Remission was maintained for 12 weeks in 74 percent of patients whose skin cleared. There were no signs of skin atrophy nor was there any effect on morning plasma cortisol levels. Maintenance therapy has recently been extended to six months.

Physicians must take measures to prevent patients from continuing to use these products without periodic follow-up visits. Patients should not be given unlimited prescription refills and should be warned not to use these drugs under occlusion. It has also been recommended that patients using a large quantity of steroids applied over a large surface area should be periodically evaluated for HPA axis suppression by assessment of plasma cortisol and urinary free cortisol levels.

REFERENCES

1. Sulzberger MB, Witten VH. The effect of topically applied compound F in selected dermatoses. J Invest Dermatol 1952;19:101-2.

2 .Parish LC, Witkowski JA, Muir JG. Topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol 1985;24:435-6.

3 .Clement M, du Vivier A. Topical steroids for skin disorders. Boston: Blackwell, 1987.

4 .Arndt KA. Manual of dermatologic therapeutics: with essentials of diagnosis. 3d ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1983:271-2.

5 .McKenzie AW, Stoughton RB. Method for composing absorption of steroids. Arch Dermatol 1962;86:608.

6. Weston WL. The use and abuse of topical steroids. Contemp Pediatr 1988;5(6):57-66.

7. Katz HI, Prawer SE, Mooney JJ, Samson CR. Preatrophy: covert sign of thinned skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;20(5 Pt 1):731-5.

8. Leyden JJ, Thew M, Kligman AM. Steroid rosacea. Arch Dermatol 1974; 110: 619-22.

9. Fritz KA, Weston WL. Topical glucocorticosteroids. Ann Allergy 1983;50(2):68-76.

10. Gill KA, Katz HI, Baxter DL. Fungus infections occurring under occlusive dressings. Arch Dermatol 1963;88:348-9.

11. Alani MD, Alani SD. Allergic contact dermatitis to corticosteroids. Ann Allergy 1972; 30(4):181-5.

12. Cox NH. Contact allergy to clobetasol propionate. Arch Dermatol 1988; 124:911-3.

13. Feingold KR, Elias PM. Endocrine-skin interactions. Cutaneous manifestations of adrenal disease, pheochromocytomas, carcinoid syndrome, sex hormone excess and deficiency, polyglandular autoimmune syndromes, multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes, and other miscellaneous disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988;19(1 Pt 1):1-20.

14. Stoughton RB, Cornell RC. Review of superpotent topical corticosteroids. Semin Dermatol 1987;6(2)-72-6.

15. Stoughton RB, Cornell RC. Topical steroid therapy. Dermatol Q 1987;june:1-3.

16. Gammon WR, Krueger GG, Van Scott EJ, et al. Intermittent short courses of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% in the treatment of psoriasis. Curr Ther Res 1987;42:419-27.

17. Katz HI, Hien NT, Prawer SE, Scott JC, Grivna EM. Betamethasone dipropionate in optimized vehicle. Intermittent pulse dosing for extended maintenance treatment of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 1987; 123:1308-11.

STEVEN E. PRAWER, M. D. is associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, and at St. Paul-Ramsey Medical Center, St. Paul. He is also in private practice in Fridley, Minn. Dr. Prawer graduated from the University of Minnesota, where he also completed a dermatology residency.

H. IRVING KATZ, M.L). is clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Minnesota and at St. Paul-Ramsey Medical Center. He also is in private practice in Fridley, Minn. A graduate of the University of Minnesota Medical School, Dr. Katz served residencies at the U.S. Naval Hospital, St. Albans, N.Y., and at the University of Minnesota.

COPYRIGHT 1990 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group