Fulminant hepatic failure is a rare complication of disulfiram treatment for alcoholism. In the instances that it does occur, previous liver disease or failure to be abstinent from alcohol are thought to be causative. This case describes fulminant hepatic failure in a patient taking disulfiram with no previous liver disease and report of being compliant with alcohol abstinence. Careful pretreatment screening and rigorous monitoring patients are recommended to help prevent this life-threatening event.

Introduction

Disulfiram is often used as an adjuvant in the treatment of soldiers diagnosed with alcoholism. Disulfiram-induced hepatitis occurs rarely with its use. Fulminant hepatic failure is an extremely uncommon side effect. The few cases reported have been associated with patients that had underlying liver disease or were noncompliant with alcohol abstinence. This case occurred in a patient that reported ethanol abstinence that was confirmed by his spouse, military command, and his case worker (Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention Committee). he had no previous history of liver disease. The clinical presentation and treatment will be reviewed. The role of disulfiram therapy will be discussed.

Case Report

A 23-year-old active duty male was evaluated in the clinic for abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. he also reported yellowing of his eyes, dark urine despite good hydration, and tan-colored stools 4 days before evaluation. he denied any mental status changes, fevers, or chills. he denied any blood transfusions, illicit drug use, unprotected intercourse, or travel outside of the United States. he also denied any use of acetaminophen or any herbal supplements. he had been started on disulfiram 1 month before presentation. Liver function chemistries were not taken before starting disulfiram. Laboratory values at presentation were as follows: serum aspartate aminotransferase, 798; alanine aminotransferase, 1,815; total bilirubin, 9.8; alkaline phosphatase, 175; lipase, 83; and prothrombin time, 14.4. He was admitted to the hospital for intravenous fluids and further studies to help determine the etiology of his hepatitis. Right upper quadrant ultrasound with Doppler of the hepatic vein showed a normal liver, normal common bile duct, and normal venous blood flow. There was evidence of gallstones, but the gall bladder was otherwise unremarkable. A computed tomography scan of abdomen was unremarkable, with no liver pathology. Serologies for viral hepatitis, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and herpes simplex virus were negative. Autoimmune and ceruloplasmin tests were unremarkable. The patient had no signs of encephalopathy. Despite 10 days of hospitalization and discontinuance of disulfiram, his condition failed to improve as evidenced by the following laboratory values: prothrombin time, 31.0' alkaline phosphatase, 206; and alanine aminotransferase, 1,360. he was transferred to a facility for consideration of liver transplant. His condition continued to worsen. Symptoms of encephalopathy occurred while he was awaiting consideration for transplant. His Child-Pugh score was 12, which corresponds to severe decompensated disease and a survival rate of 35%. He was evaluated for transplant and was found to be a candidate as status 1 for fulminant liver failure. he was counseled with his family as to the necessity of complete abstinence from alcohol as part of the agreement in transplantation. he underwent a successful liver transplantation and experienced an uneventful recovery. Upon follow-up, the patient was recovering well, and was compliant with his new medicines and with abstinence from alcohol.

Discussion

Disulfiram has been used successfully as an adjuvant with psychotherapy in the treatment of alcoholism since 1948. Initially, patients were given disulfiram and ethanol to produce the aversion reaction. In 1952, 26 fatalities were reported from the use of disulfiram, presumed as caused by myocardial ischemia.1 Thereafter, an experienced ethanol-disulfiram reaction was replaced by a physician's warning to avoid this reaction. The first large study using this method showed modest improvement in alcohol abstinence. Seventy-seven percent of self-selected participants were abstinent at 6 months of treatment, and 68% were abstinent at 12 months. The control participants receiving the same treatment minus the disulfiram were 64% abstinent at 6 months, and 66% remained abstinent at 12 months.2 Subsequent randomized trials showed those taking 250 mg each day had 49 drinking days in 12 months, those taking 1 mg each day had 75 drinking days, and those receiving placebo had 86 drinking days in 12 months.3 The 1-mg dose did not produce the aversive reaction, thus illustrating the effect of the physician warning.

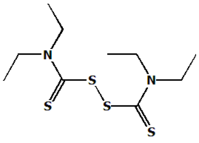

Disulfiram inhibits the hepatic enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase. With concurrent use of ethanol, serum acetaldehyde levels increase. Elevated serum acetaldehyde produces symptoms including nausea, vomiting, headache, chest pain, sweating, vertigo, anxiety, and confusion. Uncommon adverse reactions are listed as weakness, dermatitis, lethargy, loss of libido, and depression. Hepatotoxicity is rare. The first reported case of successful hepatic allograft transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure from disulfiram toxicity occurred in 1998.4 The cause of disulfiram hepatotoxicity is unknown. Theories of immunologic-mediated and carbon disulfide toxicity have been presented.5 A Veterans Administration randomly controlled study concluded that 90% of all patients with elevated serum liver enzymes were drinking, implying that compliance was poor and that liver toxicity was from noncompliance.6 Clinical recovery usually occurs within 2 weeks of discontinuance of disulfiram.7

Conclusion

Disulfiram is often used for treatment of alcoholism in active duty personnel. Significant life-threatening reactions can occur. Initiating treatment should be limited to the patient that is motivated to change, has shown compliance with the initial steps of the treatment program, and is readily available for follow-up evaluations. Initial liver function chemistries are recommended, as well as surveillance tests during the first few months; some advocate bimonthly liver enzyme chemistries during the first few months. With appropriate assessment, hepatitis and the possibility of fulminant hepatic failure can be avoided or minimized.

References

1. Jacobsen E: Deaths of alcoholic patients treated with disulfiram. Q J Stud Alcohol 1952; 13: 16-26.

2. Armor DJ, Polich J, Stambul HB: Alcoholism and Treatment, pp 146-7. New York, Wiley, 1978.

3. Fuller RK, Branchley L, Brightwell DR: Disulfiram for the treatment of alcoholism: a Veterans Administration cooperative study. J Am Med Assoc 1986; 256: 1449-55.

4. Rabkin JM, Corless CL, Orloff SL, et al: Liver transplantation for disulfiram induced hepatic failure. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93: 830-1.

5. Eliasson E, Stal P, Oksanen A, Lytton S: Expression of autoantibodies to specific cytochrome P450 in a case of disulfiram hepatitis. J Hepatol 1998; 9 29: 819-25.

6. Iber FL, Lee K, Lacoursiere R, Fuller R: Liver toxicity encountered in the Veterans Administration trial of disulfiram in alcoholics. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res 1987; 11: 301-4.

7. Wright C, Moore RD: Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism. Am J Med 1990; 88: 647-55.

Guarantor; MAJ Marshall Mendenhall, MC USA

Contributor: MAJ Marshall Mendenhall, MC USA

Department of Family Practice, Madigan Army Medical Center, Fort Lewis, WA 98431.

This manuscript was received for review in May 2003 and accepted for publication in September 2003.

Reprint & Copyright © by Association of Military Surgeons of U.S., 2004.

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Aug 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved