With all the marijuana the government has seized throughout the years, one thing appears abundantly clear: The feds still don't know the first thing about pot. At least that seems to be the case in Mississippi where the government's controversial weed farm has been besieged with complaints.

"Ditch weed" is what some critics call the pot being grown on government farms and shipped to San Mateo County, Calif., for the first-ever publicly funded analysis of HIV patients smoking joints in their homes. Characterizing the federal product as a bunch of sticks, seeds and stems with stale leaves, observers ranging from patients to a cop turned county supervisor are not high on the socialized product.

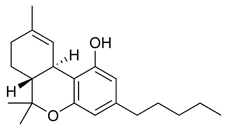

Of course those pushing for the reform of marijuana laws are quite upset as well. Some charge that the government sabotaged the study to show pot can have adverse effects on patients who are seeking help in battling AIDS and other life-threatening illnesses. When complaints started to filter out in San Mateo about the poor quality of the federal weed, Dale Gieringer, California coordinator for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), blasted the government. "It's unconscionable that they would be giving this marijuana to patients," he says. "It's stale, low-potency ditch weed." A 1999 NORML survey showed that among 48 samples, the government's pot scored the lowest on levels of THC--the active ingredient in marijuana.

The groundbreaking study, which surprisingly has been supported quietly by the Bush administration, monitors its participants via self-reports, home visits, medication logs and return of leftover marijuana cigarettes. To be accepted into the study, a participant must be HIV-positive and suffering from neuropathy, a condition that afflicts AIDS, diabetes and other patients with severe tingling and pain in their hands and feet. Participants must have used pot before, have no record of other drug abuse, enjoy a stable home life and keep the government joints in a locked box.

"We have no interest, at present, in introducing people to marijuana use" claimed Dennis Israelski, chief of infectious disease and AIDS medicine at San Mateo County Health Center, when announcing the pilot program, which operates with about 600 marijuana cigarettes from the Mississippi pot farm kept in a hospital freezer. The study has a budget of $500,000 and is expected to last perhaps a year. About 30 joints per week are supplied to each patient. At first the patient smokes only in a special room in the health center but then is allowed to take the stash home.

But attracting qualified participants has been a serious problem ever since San Mateo County received the go-ahead about a year ago from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In fact, afar several months of screening patients, the county had only one patient who fit all the stringent criteria. That was free-lance journalist and AIDS activist Phillip Alden. Each week he would receive his federally grown marijuana cigarettes to smoke in his home.

But Alden tells INSIGHT he couldn't finish the study. "I was unable to complete the last week because I developed an upper respiratory infection similar to bronchitis," he says. The illness more than likely came from the substandard product, critics say. "The smoke was old, it contained seeds which taste awful when they burn and it was harsh on my throat," Alden says.

Since Alden left the program, fewer than a dozen patients have participated--far short of the 60 patients San Mateo County had hoped to use as human guinea pigs for the clinical trial.

Some say the county's inability to attract suitable patients might be linked to word on the street that the free pot being provided is unsmokable. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which grows the Mississippi farm weed, insists the problem is not with socialism but with dehumidifying. Steve Gust, special assistant to the director of NIDA, admitted to the San Jose Mercury News that the federal stash is "harsh." But he dismissed the NORML complaints as simply coming from biased activists looking for someone to blame if the results from the study show marijuana has little medicinal value for HIV/AIDS treatment.

But Alden's public disclosure about the low-grade federal pot may have hurt efforts to attract HIV patients. In response, researchers recently asked for FDA permission to expand the base of potential patients to include those suffering from nausea and eating disorders. More recently, on May 14, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against a claimed constitutional right to marijuana for medicinal purposes, which initially created alarm that such studies might cease.

The ruling sent chills up the back of people such as Alden who worry about what he calls "rampant federalism" spreading across the nation. "It started before 9/11 and has only gotten worse," he says. "How a state chooses to care for its ill residents should not be subjugated by people outside the state." So far, however, the Supreme Court ruling has not affected the study, which Alden hopes will continue despite the poor product.

Expanding the study to include others will be another hurdle to overcome for a program that has taken almost three years to put together, says San Mateo County Board of Supervisors President Mike Nevin, a former San Francisco cop who used to bust those who engaged in illegal trafficking of marijuana. San Mateo began clinical trials last July after an exhausting and burdensome regulatory process and now will have to wait for another regulatory approval to expand the participant base.

As a former cop, Nevin admits he initially had reservations about the study, but tells INSIGHT he became convinced after a close friend, Joni Commons, who was deputy director of the county's health services, confided to him that smoking pot was the only thing that relieved her otherwise constant nausea from chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer. Commons eventually died, but Nevin says he was inspired to try to help others. "We need scientific proof. The federal government never had the courage to do the study, so San Mateo is doing it now," he says.

Nevin initially approached the San Mateo County Health Center about using pot confiscated by police, but that was turned down and the federally approved clinical cannabis study was born. But the recent problems from the inferior quality has certainly "hurt our efforts," Nevin admits. "Right now all we are trying to do is get a scientific finding to determine if marijuana should be pharmaceutically prescribed by a doctor."

If it does work, Nevin thinks people may get the wrong impression that San Mateo will be handing out joints to all comers. Instead, he says, cannabinoids might be placed in an inhalable substance similar to pharmaceutical inhalants used by those who suffer from asthma.

Currently, the only prescribable cannabinoids are THC (dronabinol, Marinol) and the dronabinol derivative nabilone. THC has been successful in destroying brain cancer in rats. Marinol was approved in the United States as a nausea drug in 1985 and as an appetite stimulant for AIDS patients in 1992. More recently, several large pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, have expressed interest in the medical use of cannabinoids and their derivatives. Previously the companies had turned away from marketing pot as a medicine because of political and cost problems.

In the meantime, Nevin says the quality of the pot has to get better or the trial is going to be deemed a failure. But even if the San Mateo study becomes a total bust, other jurisdictions have taken note. In fact, medicinal-marijuana research slowly is taking hold in other parts of the country. The Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research in La Jolla, Calif., plans to oversee studies at more than a dozen university sites. The clinical trials at the center will cost the University of California-San Diego and the University of California-San Francisco about $841,000 and more in other state funds.

The studies will investigate whether smoking marijuana can alleviate neuropathy. One study will focus on patients in hospitals, while the other will serve outpatients. Yet another study will look at how pot affects the ability of patients with HIV-related neuropathy or multiple sclerosis to drive a car, and another will look at whether pot eases the uncontrollable muscle spasms and pain associated with multiple sclerosis.

Initial reports indicate that the Southern California patients in the La Jolla studies also are complaining about the federal government's Mississippi farm weed. But these complaints are a little different. "Too potent," say at least two subjects, who claim they want relief rather than to get stoned. At least these complaints do not seem to be driving away patients. La Jolla currently has a waiting list of 500 eager participants hoping to get their take-home tokes.

TIMOTHY W. MAIER IS A WRITER FOR Insight.

COPYRIGHT 2002 News World Communications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group