Abstract

Objective To evaluate the efficacy and safety of galantamine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease.

Design Randomised, double blind, parallel group, placebo controlled trial.

Setting 86 outpatient clinics in Europe and Canada.

Participants 653 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease.

Intervention Patients randomly assigned to galantamine had their daily dose escalated over three to four weeks to maintenance doses of 24 or 32 mg.

Main outcome measures Scores on the 11 item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale, the clinician's interview based impression of change plus caregiver input, and the disability assessment for dementia scale. The effect of apolipoprotein E4 genotype on response to treatment was also assessed.

Results At six months, patients who received galantamine had a significantly better outcome on the 11 item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale than patients in the placebo group (mean treatment effect 2.9 points for lower dose and 3.1 for higher dose, intention to treat analysis, P [is less than] 0.001 for both doses). Galantamine was more effective than placebo on the clinician's interview based impression of change plus caregiver input (P [is less than] 0.05 for both doses v placebo). At six months, patients in the higher dose galantamine group had significantly better scores on the disability assessment for dementia scale than patients in the placebo group (mean treatment effect 3.4 points, P [is less than] 0.05). Apolipoprotein E genotype had no effect on the efficacy of galantamine. 80% (525) of patients completed the study.

Conclusion Galantamine is effective and well tolerated in Alzheimer's disease. As galantamine slowed the decline of functional ability as well as cognition, its effects are likely to be clinically relevant.

Introduction

Cholinergic deficits are the most prominent neurochemical disturbances in patients with Alzheimer's disease and are thought to contribute to the deterioration in memory and other cognitive functions.[1] Several pharmacological approaches have been used in an attempt to correct these deficits.[2] Of these strategies, inhibition of acetylcholinesterase is currently the most successful treatment for Alzheimer's disease.[3] Well designed clinical trials have consistently shown improved cognition and global assessment scores in patients taking acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.[3 4] The effects of cholinesterase inhibitors on patients' activities of daily living are unclear.[5 6] There is also some evidence that patients who have the apolipoprotein E4 genotype may have a reduced response to cholinesterase inhibitors.[7 8]

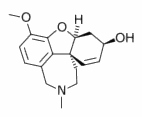

Galantamine is a new drug that reversibly and competitively inhibits acetylcholinesterase[9 10] and enhances the response of nicotinic receptors to acetylcholine.[11]

We evaluated the efficacy and safety of two maintenance doses of galantamine over six months compared with placebo in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. We also investigated whether the apolipoprotein E4 genotype influences the response to galantamine.

Participants and methods

We studied outpatients who had a history of cognitive decline that had been gradual in onset and progressive over at least six months. Participants had to meet the criteria for probable Alzheimer's disease[12] and to have mild to moderate dementia, defined as a score of 11-24 on the mini-mental state examination[13] and a score of [is greater than or equal to] 12 on the 11 item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale.[14] Patients had to live with, or be visited at least five days a week by, a responsible caregiver. Patients with concomitant diseases were included in the study provided that their illness was controlled.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had any other neurodegenerative disorder; multi-infarct dementia or clinically active cerebrovascular disease; cardiovascular disease thought likely to prevent completion of the study; clinically important cerebrovascular, psychiatric, hepatic, renal, pulmonary, metabolic, or endocrine conditions or urinary outflow obstruction; an active peptic ulcer; or any history of epilepsy or serious drug or alcohol misuse. We also excluded patients who had been treated for Alzheimer's disease with a cholinesterase inhibitor. A blood sample was taken at baseline for apolipoprotein E genotyping.[15]

The caregiver together with the patient (or their relative, guardian, or legal representative) provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions and approved by ethics committees at each centre.

Design

This was a six month, parallel group, double blind, placebo controlled trial undertaken in 86 centres in eight countries (Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom). Patients were randomly assigned to one of two galantamine treatment groups or a placebo group by simple computer generated randomisation. In both galantamine groups, the galantamine regimen was 8 mg daily for one week, increasing to 16 mg daily for the second week and to 24 mg daily for the third week. In the fourth week, one galantamine group continued on 24 mg while the other group had the dose increased to 32 mg daily.

The primary efficacy variables used in the trial were the standard 11 item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale (score range 0-70; higher scores indicate greater cognitive impairment)[14] to assess cognitive function (memory, attention, language, orientation, etc) and the clinician's interview based impression of change plus caregiver input,[16] which provides a global impression of a patient's improvement or deterioration over the course of the illness. The clinician's interview was scored relative to baseline by a clinician blinded to other assessments and was based on separate interviews with the patient and the caregiver. The primary end point was at six months.

A secondary efficacy variable was the disability assessment for dementia scale, based on an interview with the caregiver, to assess activities of daily living (self care activities, instrumental (complex) activities of daily living, planning and organisation, leisure, effective performance, initiation). The disability assessment scale uses 46 questions and has a score range of 0-100 (higher scores indicate better functioning).[17] Details of other secondary efficacy variables are available on the BMJ's website.

Safety evaluations throughout the study comprised regular physical examinations, electrocardiography, measurements of vital signs, standard laboratory tests, and monitoring for adverse events.

Statistical analysis

We estimated that we needed about 180 patients in each treatment group to achieve 80% power ([alpha] = 0.025 with a Bonferroni adjustment) to detect a 2.75 point change. This difference in the change in the 11 item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scores between patients who received galantamine and placebo after six months was considered to be clinically meaningful.

All randomised patients who took at least one dose of the trial drug were included in the analyses of baseline characteristics and safety data. We performed a six month intention to treat analysis that included all randomised patients who had any efficacy assessment whether at baseline or during treatment. The last available assessment was carried forward into all subsequent assessment times for which actual data were not available.

We used the following methods to compare variables between each galantamine group and the placebo group: analysis of variance, using treatment and country as factors; generalised Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, controlling for country, for response rates to the 11 item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale; and Van Elteren test,[18] controlling for country, for the clinician's interview based impression of change plus caregiver input. The time-response relation for change in the 11 item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale was analysed by generalised linear mixed modelling. All tests were evaluated at the 5% significance level. The statistical software used was SAS version 6.12.

Results

Of the 753 patients screened for the study, 653 were randomised to treatment (fig 1). The baseline characteristics of the three treatment groups were comparable (table 1).

[Figure 1 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of participants. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

(*) n=185 for placebo, n=184 for galantamine 24 mg, and n=179 for galantamine 32 mg.

([dagger]) 11 item cognitive subscale.

([double dagger]) Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging findings in past 12 months.

Primary efficacy variables

At six months, patients who received galantamine had significantly better cognitive function than patients in the placebo group (table 2). The difference in mean change from baseline score increased progressively Galantamine produced a better outcome than placebo on the 11 item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale regardless of the number of copies of the E4 apolipoprotein allele that a patient had (table 3).

[Figure 2 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Table 2 Change from baseline in measures of efficacy at six months, intention to treat analysis

(*) Difference from placebo.

([dagger]) Negative change from baseline indicates improvement.

([double dagger]) Negative change from baseline indicates deterioration.

([sections]) Van Elteren test was used to test for differences in the distribution of scores between placebo and galantamine groups. For details of the observed case analysis see table 2 on BMJs website.

Table 3 Change from baseline in score on 11 item cognitive subscale of Alzheimer's disease assessement scale at six months according to apolipoprotein E genotype

(*) The low patient numbers reflect the fact that many patients did not give informed consent for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

The effect of either dose of galantamine on the clinician's interview based impression of change plus caregiver input ratings was significantly better than that of placebo at six months (table 2).

After six months of treatment, the higher dose of galantamine also produced a significantly better outcome on the disability assessment for dementia scale than placebo (table 2).

Safety

At least 5% more patients in the galantamine group than in the placebo group reported nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, dizziness, headache, anorexia, and weight loss, with nausea being the most common adverse event (table 4). Most adverse events (92%) were mild to moderate in severity, and the proportion of serious adverse events was similar in the three treatment groups (12-13%).

Table 4 Adverse events for which the difference between the galantamine and placebo groups was at least 5%. Values are numbers (percentages) of patients

Discontinuations due to adverse events were more common in patients who received galantamine (18% (79/438)) than in patients in the placebo group (9% (19/215), fig 1). More patients in the higher dose group (22% (48/218)) discontinued treatment because of adverse events than in the lower dose group (14% (31/ 220)). The events most commonly associated with discontinuation from galantamine treatment were nausea and vomiting. About half of the patients who discontinued due to adverse events during galantamine treatment (43/79) stopped during the dose escalation phase.

Discussion

Our study shows that, compared with placebo, galantamine significantly improved cognition and global function in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. These therapeutic effects were associated with significant benefits on patients' activities of daily living.

Effects of other cholinesterase inhibitors

The effects of traditional cholinesterase inhibitors on activities of daily living are unclear.[6] Metrifonate was shown to have functional benefits in a six month study that used the disability assessment for dementia scale.[19] Studies on donepezil have either not reported functional benefits[20-22] or have shown benefit if basic activities of daily living (self care tasks such as dressing and personal hygiene) are removed from the analysis.[23] Rivastigmine was also shown to have favourable effects on daily activities,[24 25] although the validity of these results has been questioned.[6]

The decline in both cognitive functions and activities of daily living in the placebo group in our study was at least as great as that found in placebo groups in other comparable studies.[22-25] These data suggest that galantamine's cognitive and functional benefits are unlikely to be due to the inclusion of patients with less severe disease.

As many as 70% of patients with Alzheimer's disease carry at least one copy of apolipoprotein E4.[26] These patients seem to have a greater impairment of presynaptic cholinergic function than patients without the apolipoprotein E4 allele, which might be expected to reduce their response to treatment. However, galantamine significantly improved cognitive function, relative to placebo, regardless of patients' apolipoprotein E genotype. These findings contrast with results for tacrine[8] but agree with a recent pooled analysis of metrifonate studies.[27]

Side effects

Galantamine was well tolerated by most patients. The completion rates for the two galantamine groups were comparable to those reported for other cholinesterase inhibitors.[22-25] More adverse events were reported with the higher dose, and more patients who received the higher dose discontinued treatment due to adverse events. The most common adverse event in the galantamine groups was nausea, which has also been reported with other cholinesterase inhibitors.[22 23 25] For most patients in our study, nausea was mild to moderate and lasted a median of five to six days.

The monthly rate of discontinuations due to adverse events with galantamine was comparable to the rate with placebo during the maintenance phase of the study, suggesting that the rapid, rigid dose escalation procedure may have contributed to patients discontinuing galantamine treatment. In a recent, five month, placebo controlled study of galantamine, in which the dose was escalated over eight weeks, the proportion of patients who discontinued galantamine 24 mg/day due to adverse events was low (10%) and comparable to that in the placebo group (7%).[28] In clinical practice, patients' tolerance of galantamine might be improved by starting at a low dose and escalating the dose slowly.

What is already known on this topic

Alzheimer's disease is characterised by a progressive decline in patients' cognitive function and ability to perform daffy activities

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have been shown to improve cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer's disease

It is unclear whether changes in cognitive function, as measured on a psychometric scale, translate into clinically important outcomes for patients and their caters

What this study adds

Galantamine significantly improved cognitive function relative to placebo over six months

Treatment also slowed the progression of functional decline

The beneficial effect was evident in patients with and without the apolipoprotein E4 allele

The clinical investigators for the study were as follows:

Canada: Addington D, Ancill R, Bergman H, Campbell B, Feldman H, Hutchings R, McCracken P, McKelvey R, Mohr E, Nair V, Naranjo C, Rabheru K, Rajput A, Robillard A, Van Reekum R, Veloso F. Finland: Alhainen K, Erkinjuntti T, Hedman C, Jolma T, Koivisto K, Pirttila T, Rinne J, Sulkava R, Tarvainen I. France: Auriacombe S, Benoit M, Borsotti J, Bouchacourt M, Boulliat J, Dourneau M, Feteanu D, Gras P, Guard O, Hourant C, Joyeux O, Lemarquis P, Rageot P, Rouch I, Verlhac B. Germany: Benkert O, Frolich L, Hampel H, Heinze H, Horn R, Jauss M, Kessler C, Kornhuber J, Kurz A, Moller H, Rosler M, Schroder J, Uebelhack R, Wiltfang J. Netherlands: Dautzenberg P, Eerenberg J, Groeneveld W, Kleyweg R, Pop P, Sanders E, Scheltens P, Siebenga E, van der Cammen T, Wiezer J, Wouters C. Norway: Bjornson L, Hoprekstad D, Nygaard H, Pettersen R, Radunovic Z, Sletvold O, Sparr S. Sweden: Ahlin A, Andersson E, Andreasen N, Edman A, Elofsson G, Eriksson L, Hansson G, Karlson I, Karlsson M, Kilander L, Klingen S, Mahnfeldt M, Marcusson J, Minthon L, Nagga K, Olofsson H, Passant U, Sjogren M, Syversen S, Wallin A, Werner-Bengtsson L. United Kingdom: Bamrah J, Bullock R, Grimley Evans J, Katona C, Livingston G, O'Malley P, McKeith I, Somerville W, Thompson P, Vethanayagam S, Waite J, Wilcock G, Wilkinson D.

Contributors: GKW and SL participated in the design and execution of the study as well as analysis of data and writing the paper. EG participated in analysing and interpreting the data and writing the paper. GKW will act as the guarantor for the paper.

Funding: The study was supported by funding from Janssen Research Foundation, Beerse, Belgium.

Competing interests: GKW's department receives research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals Group and Janssen Pharmaceutica, who have codeveloped galantamine. GKW has received consultancy fees from Shire Pharmaceuticals Group and Janssen Pharmaceutica.

Gordon K Wilcock, Sean Lilienfeld, Els Gaens on behalf of the Galantamine International-1 Study Group

[1] Bartus RT, Dean RL, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science 1982;217:408-14.

[2] Allen NHP, Burns A. The treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Psychopharmacol 1995;9:43-56.

[3] Nordberg A, Svensson A-L. Cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a comparison of tolerability and pharmacology. Drug Saf 1998;19:465-80.

[4] Schneider LS. New therapeutic approaches to Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57(suppl 14):30-6.

[5] Pryse-Phillips W. Do we have drugs for dementia? Arch Neurol 1999;56:735-7.

[6] Bentham P, Gray R, Sellwood E, Raftery J. Effectiveness of rivastigmine in Alzheimer's disease. BMJ 1999;319:640.

[7] MacGowan SH, Wilcock G, Scott M. Effect of gender and apolipoprotein E genotype on response to acetylcholinesterase therapy in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 1998; 13:625-30.

[8] Farlow MR, Lahiri DK, Poirer J, Davignon J, Hui SL. Treatment outcome of tacrine therapy depends on apolipoprotein genotype and gender of the subjects with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1998;50:669-77.

[9]Bores GM, Huger FP, Petko W, Mutlib AE, Camacho F, Rush DK, et al. Pharmacological evaluation of novel Alzheimer's disease therapeutics: acetylcholinesterase inhibitors related to galanthamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996;277:728-38.

[10] Vasilenko ET, Tonkopii VD. Characteristics of galanthamine as a reversible inhibitor of cholinesterase. Biokhimiia 1974;39:701-3.

[11] Albuquerque EX, Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Castro NG, Schrauenholz A, Barbosa CT, et al. Properties of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: pharmacological characterization and modulation of synaptic function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997;280:1117-36.

[12] McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS/ ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1984;34:939-44.

[13] Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state" A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98.

[14] Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1984;141:1356-64.

[15] Wendham PR, Price WH, Blundell G. Apolipoprotein E genotyping by one-stage PCR. Lancet 1991 ;337:1158-9.

[16] Schneider LS, Olin JT, Doody RS, Clark CM, Morris JC, Reisberg B, et al. Validity and reliability of the Alzheimer's disease cooperative study-clinical global impression of change. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997;11 (suppl 2):22-32.

[17] Gelinas I, Gauthier L, McIntyre M, Gauthier S. Development of a functional measure for persons with Alzheimer's disease: the disability assessment for dementia. Am J Occup Ther 1999;53:471-81.

[18] Van Elteren PH. On the combination of independent two sample tests of Wilcoxon. Bull Inst Intern Statist 1960;37:351-61.

[19] Dubois B, McKeith I, Orgogozo J-M, Collins O, Meuliens D, MALT Study (group. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy, tolerability and safety of two doses of metri-fonate in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: the MALT study, Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:973-82.

[20] Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT, Donepezil Study Group. The efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease: results of US multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dementia 1996;7:293-303.

[21] Rogers SL, Doody RS, Mohs RC, Friedhoff LT, Donepezil Study Group. Donepezil improves cognition and global function in Alzheimer disease. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1021-31.

[22] Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT, Donepezil Study Group. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1998;50:136-45.

[23] Burns A, Rossor M, Hecker J, Gauthier S, Petit H, Moller H-J, et al. The effects of donepezil in Alzheimer's disease--results from a multinational trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999; 10:237-44.

[24] Corey-Bloom J, Anand R, Veach J, ENA 713 B352 Study Group. A randomized trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of ENA 713 (rivastigmine tartrate), a new acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, in patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychopharmacol 1998;1:55-65.

[25] Rosler M, Anand R, Cicin-Sain A, Gauthier S, Agid Y, Dal-Bianco P, et al. Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer's disease: international randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1999;318:633-8.

[26] Higgins GA, Large CH, Rupnik HT, Barnes JC. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer's disease: a review of recent studies. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1997;56:675-85.

[27] Farlow MR, Cyrus PA, Nadel A, Lahiri DK, Brashear A, Gulanski B. Metrifonate treatment of AD: influence of APOE genotype. Neurology 1999;53:2010-6.

[28] Tariot P, Solomon P, Morris J, Kershaw P, Lilienfeld S, Parys W, et al. A 5-month, randomized, placebo-controlled study of galantamine in AD. Neurology 2000;54:2269-76.

(Accepted 10 August 2000)

Department of Care of the Elderly, Frenchay Hospital, University of Bristol, Bristol BS16 1LE

Gordon K Wilcock professor in care of the elderly

Central Nervous System Clinical Research, Janssen Research Foundation, Beerse, Belgium

Sean Lilienfeld director

Els Gaens statistician

Correspondence to: G K Wilcock Gordon.Wilcock@ bris.ac.uk

Clinical investigators in the Galantamine International- 1 Study Group are listed at the end of the paper.

BMJ 2000;321:1445-9

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group