Study objective: Vinorelbine and gemcitabine are two active single agents used in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A clinical trial was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of vinorelbine plus gemcitabine in patients with inoperable (stage IIIB or IV) NSCLC.

Design: A multicenter phase II study. Vinorelbine, 20 mg/[m.sup.2], was given as a 10-min IV infusion, followed by a 30-min IV infusion of gemcitabine, 800 mg/[m.sup.2], on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle.

Patients and measurements: From March 1998 to August 1998, 40 patients were enrolled in the study. The efficacy and toxicity of the treatment were recorded.

Results: All patients are evaluable for treatment response and toxicity profile. Two patients achieved a complete response, and 27 patients achieved a partial response, with an overall response rate of 72.5% (95% confidence interval, 58.7 to 86.3%). Median survival time was 11 months. The significant (World Health Organization grade, 3/4) toxicities were myelosuppression, including leukopenia (47.5% of patients), anemia (17.5% of patients), and thrombocytopenia (12.5% of patients). However, febrile neutropenia occurred in three patients and accounted for one treatment-related death. Fatigue, or flu-like syndrome, occurred in 17 patients, and the symptoms were reversed spontaneously 1 to 2 days after injection in 10 patients. Another seven patients needed dose reduction to ameliorate symptoms. Interstitial pneumonitis occurred in six patients who recovered after steroid treatment. No patient suffered from grade 3 or 4 nausea/vomiting.

Conclusion: The combination of vinorelbine and gemcitabine in patients with advanced NSCLC is a highly active non-cisplatin-containing regimen with an acceptable toxicity profile.

(CHEST 2000; 117:1583-1589)

Key words: gemcitabine; non-small cell lung cancer; vinorelbine

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; WHO = World Health Organization

Worldwide, lung cancer was the most common cancer in 1990 in terms of both incidence (1.04 million new cases) and mortality (921,000 deaths). It is the most common cancer in men, with the highest rates observed in Eastern Europe (incidence, 75.85 cases per 100,000 population) and North America (incidence, 69.62 cases per 100,000 population). Incidence rates are lower in women, with the highest rates observed in North America (incidence, 32.91 cases per 100,000 population) and North Europe (incidence, 20.21 cases per 100,000 population).[1] Because the majority of patients with lung cancer have tumors with a non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) histology and because [is greater than] 75% of tumors in NSCLC patients are inoperable at the time of presentation, the prognosis of such patients is poor. The reported 5-year survival was 14% in the United States and 8% in Europe.[1] The high proportion of disseminated disease and poor prognosis in such patients have justified the continued efforts at developing new chemotherapeutic options.

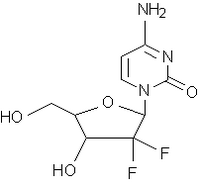

Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analog with confirmed activity against several solid tumors, especially NSCLC.[2-5] It is well-tolerated when given in doses of 1,000 to 1,250 mg/[m.sup.2] weekly x 3, followed by 1 week of rest.[2-4] Single-drug response rates of around 21% have been reported for NSCLC.[5] The preliminary results of a phase III randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin with cisplatin alone found that patients treated with both agents had a better response rate and higher median survival time than with cisplatin alone.[6] Vinorelbine is a semisynthetic vinca alkaloid with the ability to cause dissolution of the mitotic spindle apparatus and, thus, metaphase arrest in dividing cells. Single-drug response rates of 20% also have been reported for NSCLC.[5] Phase III trials comparing vinorelbine plus cisplatin with vinorelbine alone, with other agents or with vinorelbine plus cisplatin, and with cisplatin alone, have been reported.[7,8] Both studies showed that the combination of vinorelbine plus cisplatin attained a better response rate, and one study showed improved survival time. However, toxicities were more frequently found in the combination therapy with cisplatin in these phase III trials, whether they included gemcitabine or vinorelbine.[6-8]

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy is widely used in NSCLC management. GI and bone marrow toxicities induced by cisplatin with/without other agents are still a major concern of both physicians and patients. We previously performed a phase II randomized trial of single-agent gemcitabine vs the combination of cisplatin plus etoposide in patients with NSCLC and found that GI toxicities and myelosuppression were more frequent and severe in patients receiving cisplatin and etoposide.[4] In order to find a highly effective and safe regimen for NSCLC, we conducted the present study by combining gemcitabine and vinorelbine treatment in patients with inoperable locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC.

In a phase I study of the vinorelbine plus gemcitabine combination, the phase II recommended dose emanating thereof was vinorelbine, 30 mg/[m.sup.2], followed by gemcitabine, 1,200 mg/[m.sup.2], on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle.[9] The results of our own study of single-agent gemcitabine administered in Chinese patients at a dose of 1,250 mg/[m.sup.2] on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle showed that 3.7% of patients had grades 3 and 4 leukopenia and that 7.4% had grades 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia.[4] Our experience with vinorelbine, 30 mg/[m.sup.2] IV on days 1 and 5, and cisplatin, 80 mg/[m.sup.2] on day 1 of a 21-day cycle, showed that 83% of patients had grades 3 and 4 neutropenia in the mid-cycle of treatment.[10] Therefore, it was decided to administer vinorelbine plus gemcitabine to attain the 60 mg/2,400 mg total dose over 3 weeks but to add a 1-week rest period after that.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration and existing rules for good clinical practice, and the protocol was approved by the local ethics committee and the Department of Health of the Republic of China. Signed informed consent was obtained from patients. Patients with the following criteria were eligible for the study: cytologic or histologic diagnosis of locally advanced (stage IIIB) or metastatic (stage IV) NSCLC; age [is greater than or equal to] 18 years; no prior chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiotherapy; a performance status of 0 to 2 on the World Health Organization (WHO) scale; bidimensionally measurable disease; an estimated life expectancy of at least 12 weeks; adequate bone marrow reserve, with WBC count [is greater than or equal to] 4,000/[mm.sup.3], platelet count [is greater than or equal to] 100,000/[mm.sup.3], and hemoglobin count [is greater than or equal to] 10 g/dL; and female patients using appropriate methods of contraception. Patients with the following criteria were excluded from the study: signs or symptoms of brain metastases; myocardial infarction [is less than] 3 months before the date of diagnosis; superior vena cava syndrome; inadequate liver function (ie, bilirubin [is less than] 1.5 times the upper limit of normal; and serum alanine aminotransferase or serum aspartate aminotransferase [is greater than] 3 times the upper limit of normal); inadequate renal function (ie, creatinine level, [is greater than] 2.0 mg/dL); and second primary malignancy, except for in situ carcinoma of the cervix or adequately treated basal cell carcinoma of the skin.

Treatment Plan

Eligible patients were treated with vinorelbine plus gemcitabine for up to 6 cycles of 4 weeks per cycle. The treatment consisted of vinorelbine, 20 mg/[m.sup.2] IV infusion over 10 min, followed by gemcitabine, 800 mg/[m.sup.2] IV for 30 min on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks. All infusions were given through an implantable subcutaneous injection chamber (port A) or central venous lines. Dexamethasone and metoclopramide were given before chemotherapy as antiemetic prophylaxis.

With regard to dose modifications within a cycle, the dose of vinorelbine and gemcitabine was reduced by 50% if the absolute neutrophil count was between 1.5 and 1.0 x [10.sup.9]/L and/or the platelet count was 99 to 75 x [10.sup.9]/L on the day of the scheduled chemotherapy. The dose was omitted if the absolute neutrophil count was [is less than] 1.0 x [10.sup.9]/L or if the platelet count was [is less than] 75 x [10.sup.9]/ L. The subsequent course of chemotherapy was begun on day 22 if chemotherapy on day 15 was omitted. For dose adjustments in the subsequent cycle, a 50% reduction in vinorelbine and gemcitabine was instituted when the patient suffered from grade 4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia. Subsequent dose escalation to the original dosage was allowed, providing that the patient tolerated the doses given at the 50% level. For nonhematologic toxicities, vinorelbine and gemcitabine were reduced to half dose, both during a cycle and for subsequent cycles, if there were grade 3 toxicities and were omitted if there were grade 4 toxicities, excluding those due to nausea/vomiting and alopecia.

After maximal effective chemotherapy, radiotherapy was given to all stage IIIB patients, excluding those with malignant pleural effusions.

Response Evaluation

The initial workup included documentation of the patient's history, physical examination, and performance score. A CBC count, urinalysis, serum biochemistry profile, ECG, chest roentgenography, whole-body bone scan, brain CT scan, and chest CT scan also were performed.

Before and after each injection of the chemotherapeutic agent, the patient's vital signs and temperature were recorded. The patient's performance status was documented weekly throughout therapy. Disease-related symptoms (eg, pain, dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis) were recorded at study entry and before each course of chemotherapy. A CBC count was repeated before every injection. A serum biochemistry test was performed before every course of chemotherapy and during the course, if clinically indicated. Chest roentgenography and ECG were performed before every course of chemotherapy.

Responses and study drug-related toxicities were evaluated according to WHO criteria.[11] Patients' responses were reevaluated after every two cycles. A complete response was defined as the disappearance of all known disease, as determined by two observations not [is less than] 4 weeks apart. A partial response was defined as a [is greater than] 50% decrease in the total tumor size of the measurable lesions by two observations not [is less than] 4 weeks apart, without the appearance of new lesions or progression of any lesion. In responding patients and in patients with stable disease, a maximum of six cycles of chemotherapy was given. Those patients whose tumors progressed were taken off the study as soon as this finding was documented clinically and/or radiographically. All adverse events, whether thought to be due to chemotherapy or not, were recorded.

Statistical Method

A Simon two-stage phase II design was used to estimate patient accrual targets.[12] It was estimated that the power of this study to detect a true response rate of 40% was 0.9, requiring the accrual of 54 patients. Forty patients had been accrued at the end of study.

The time to disease progression was calculated from the date the patient entered the study to the date of disease progression. The duration of response was calculated from the date of the patient's response, as documented by the measurement of measurable lesion(s), to the date of disease progression or last follow-up. Survival time was measured from the date the patient entered the study to the date of death or last follow-up. Survival curves were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. All comparisons of response rates and toxicity incidences were performed by means of the Pearson [chi square] test.

RESULTS

Patients

From March to August 1998, 40 patients were registered for this study, including 32 men and 8 women. The clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. All patients were assessable for toxicity profile and treatment response.

Treatment Received

A total of 180 cycles of treatment was administered. The median number of treatment cycles was five cycles per patient, with a range of one to six cycles. Excluding one patient who died from disease progression, all patients received two or more cycles. Dose reduction was necessary in 31 patients due to myelosuppression (23 patients), severe fatigue (6 patients), hepatotoxicity (1 patient), and both myelosuppression and fatigue (1 patient). The percentage of the dose administered is shown in Table 2, with 96.1% of scheduled dose administered on day 1, 90.6% of scheduled doses administered on day 8, and 65.8% of scheduled doses administered on day 15. Of the 11 patients with stage IIIB disease (without malignant effusions), 9 patients received radiotherapy after 4 to 6 cycles of chemotherapy, 1 patient was not eligible for radiotherapy because of inadequate pulmonary reserve, and 1 patient refused radiotherapy.

Table 2--Vinorelbine and Gemcitabine Administration in Each Cycle(*)

(*) Total of 180 cycles of chemotherapy in 40 patients.

([dagger]) Scheduled treatment was not administered on days 8 or 15 because of disease progression or death in 6 patients.

Response

After two cycles of treatment, two patients achieved a complete response and 27 patients achieved a partial response, with an overall response rate of 72.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 58.7 to 86.3%; Table 3). There was improvement in pain control in 9 of 17 patients, dyspnea abated in 12 of 27 patients, cough was decreased in 21 of 32 patients, and hemoptysis resolved in 7 of 11 patients.

Table 3--Overall Response Rate in 40 Assessable Patients

(*) Pearson's [chi square] test.

The median response duration was 7.1 months (range, 1.1 to [is greater than] 13.8 months). The patient with the shortest duration of response died from neutropenic sepsis that was refractory to antibiotic and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment several days after a partial response was established (4 weeks after the initial documentation of partial response). The patients' clinical characteristics did not correlate with the response rate. However, those patients with squamous cell carcinoma were less likely to respond to treatment when compared with adenocarcinoma or NSCLC of an unspecified type (p = 0.033). The median time to disease progression was 7.3 months. The median survival time was 11 months (95% CI, 6.6 to 15.2 months) (Fig 1), although the radiotherapy given to the nine stage IIIB patients may have positively impacted their survival data. The 1-year survival rate was 48.1%.

[Figure 1 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Toxicity

All patients enrolled in the study were eligible for toxicity evaluation. The main toxicities were hematologic. The incidences of WHO grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities per patient were the following: leukopenia, 47.5%; neutropenia, 52.5%; thrombocytopenia, 12.5%; and anemia, 20%. The incidences of WHO grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities per cycle were the following: leukopenia, 18.3%; neutropenia, 23.9%; thrombocytopenia, 4.5%; and anemia, 4.5% (Table 4). Febrile neutropenia occurred in 3 of 40 patients (7.5%) and accounted for the only death from toxicicity in this study. There were several other nonhematologic toxicities (Table 5). Skin rash occurred in the early phase of treatment (10 patients had occurrence from cycle 1 treatment) and did not recur or decreased in severity with subsequent chemotherapy. Fatigue or flu-like syndrome usually occurred at the beginning of cycle 2 (12 patients), with the incidence increasing from 37 to 43% from cycle 3 to cycle 5. However, the majority of patients recovered 1 to 2 days after chemotherapy treatment, and only seven patients needed to decrease the dose due to a persistent sensation of fatigue. No patients needed to stop treatment due to this symptom. Other possible toxicities included the following: grade 1 alopecia in 25 patients; interstitial pneumonitis in 6 patients, which was radiologically localized in 5 patients and was diffuse in 1 patient, was physiologically manifested as mild respiratory alkalosis, and was relieved by steroid and oxygen therapy; port A thrombosis in 4 patients; port A cellulitis in 4 patients; extravasation in 1 patient; dizziness in 2 patients; depression in 1 patient; an episode of uneventful cerebral infract in 1 patient; myalgia in 1 patient; grade 1 diarrhea in 2 patients; and tachycardia in 1 patient.

(*) Values given as percent of patients. Assignments of toxicity represent the worst grade noted either under treatment or during follow-up.

The patients' clinical characteristics, including sex, age, performance status, and staging, were not related to grade 3 or 4 myelosuppression. There also was no correlation of these characteristics with occurrences of fatigue or hypersensitivity pneumonitis (both conditions, p [is greater than] 0.05). However, skin rashes were more likely to occur in patients [is less than] 70 years old (p = 0.049) or in those with good performance (p = 0.023).

DISCUSSION

Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy has been widely used in NSCLC patients for 2 decades. It has been found that a cisplatin-containing regimen can prolong patients' median survival time for 1 to 2 months compared to the best supportive care alone.[5,13-15] The response rate from phase II trials of combination chemotherapy containing platinum for NSCLC ranges widely from 10 to 50% but has been approximately 25% in large phase III randomized trials for NSCLC,[15] a response rate that is higher than that of a decade ago. Despite these improvements, GI and bone marrow toxicity induced by the cisplatin-containing regimen is still a major concern in the treatment of cancer patients when the patients' quality of life is taken into account during treatment, in addition to the prolonging of patients' limited life span.

The majority of our patients did not have any nausea or vomiting during the treatment period (60% of the patients or 87.2% of the cycles). Myelo-suppression was also mild, with rapid recovery. Despite the 52.5% of patients who suffered from grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, only three patients experienced febrile episodes. Fatigue or flu-like syndromes became a relatively more irksome issue for our patients when GI and bone marrow toxicity was mild. Among the 17 patients who experienced these symptoms, dose reduction was necessary in 7, which brought a complete subsiding of the symptoms. The remaining 10 patients needed frequent rest for 1 to 2 days after each injection. Few patients suffered from alopecia, and no patient needed a wig. Most of the patients did not change their work and/or daily activities during the study period. Another important finding in our study is that there was no significant difference in drug-induced toxicity and treatment efficacy between young and aged patients. Taken together, toxicity induced by this non-cisplatin-containing regimen was acceptable and less toxic than the cisplatin-containing regimen when compared to historical control subjects from a cisplatin plus etoposide study performed 3 years previously.[4]

It has been found that good performance status and relatively early-stage disease are two important factors predicting higher response rates in phase II trials.[13,15,16] The response rates of phase II trials using gemcitabine plus cisplatin varied from 28 to 54%; the drug sequence of gemcitabine and cisplatin was found to be an independent factor predicting a high response rate and survival from these studies.[17] To our knowledge there was only one reported phase II study using gemcitabine and vinorelbine treatment in patients with NSCLC before the end of October 1999. The response rate and survival time were poorer than in the present study mainly because the earlier study included aged patients who could not receive cisplatin treatment.[18] There are another four trials (results in abstract form) in which gemcitabine and vinorelbine treatment has been given to inoperable, chemotherapy-naive patients with NSCLC.[19-22] The projected gemcitabine and vinorelbine dose intensity in those studies was 600 to 800 mg/[m.sup.2]/wk and 17.5 to 20 mg/[m.sup.2]/wk, respectively. The gemcitabine and vinorelbine dose intensity attained in the present study was 600 mg/[m.sup.2]/wk and 15 mg/[m.sup.2]/wk, respectively. The response rate of 72.5% (95% CI, 58.7 to 86.3%) in our study is much higher than that reported in other studies[19-22] and may be partly attributed to the larger number of stage IIIB patients included in this study. Any contribution from drug scheduling may be more evident after the other clinical trials using the gemcitabine plus vinorelbine combination are published. There have been two phase II clinical trials of triplet therapies with gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and cisplatin.[23,24] The response rate and median survival time of these two studies were 57% and 11.7 months[23] and 65% and 13 months,[24] respectively. There was no significant difference in response rate and median survival time between these two studies and ours. To determine whether it is better to add cisplatin to gemcitabine and vinorelbine, or not, would require a phase III trial for documentation. However, our intent is to find an effective regimen without cisplatin to avoid its notorious GI side effects.

Histology was found to be a significant factor predicting response to treatment in this study. Adenocarcinoma and an unspecified cell type had very high response rates (up to 89%); even squamous cell carcinoma, a less chemosensitive subtype, attained a 46.2% response rate (6 of 13 patients). However, this study population was small, and only further studies can confirm this observation. The improvements in response rate and survival time made by chemotherapy in patients with NSCLC today are closing in the values for patients with small cell lung cancer.[5]

In this study, vinorelbine and gemcitabine combination chemotherapy is demonstrated as a highly effective, safe, and non-cisplatin-containing treatment against NSCLC. Randomized studies are needed to confirm its efficacy and safety profiles against the cisplatin-containing regimen.

REFERENCES

[1] Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 1999; 49:33-64

[2] Abratt RP, Bezwoda WR, Falkson G, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of gemcitabine in non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12:1535-1540

[3] Anderson H, Lund B, Bach F, et al. Single-agent activity of weekly gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12:1821-1826

[4] Perng RP, Chen YM, Liu JM, et al. Gemcitabine versus the combination of cisplatin and etoposide in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer in a phase II randomized study. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15:2097-2102

[5] Bunn PA Jr, Kelly K. New chemotherapeutic agents prolong survival and improve quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer: a review of the literature and future directions. Clin Cancer Res 1998; 4:1087-1100

[6] Sandler A, Nemunaitis J, Dehnamc, et al. Phase III study of cisplatin (C) with or without gemcitabine (G) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet 1998; 17:454a

[7] Le Chevalier T, Brisgand D, Douillard JY, et al. Randomized study of vinorelbine and cisplatin versus vindesine and cisplatin versus vinorelbine alone in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results of a European multicenter trial including 612 patients. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12:360-367

[8] Wozniak AJ, Crowley JJ, Balcerzak SP, et al. Randomized trial comparing cisplatin with cisplatin plus vinorelbine in the treatment of advanced n0on-small-cell-lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16:2459-2465

[9] Lorusso V, Carpagnano F, Di Rienzo G, et al. Combination of gemcitabine and vinorelbine in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a phase I-II study [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet 1997; 16:A1628

[10] Perng RP, Shih JF, Chen YM, et al. A phase II trial of vinorelbine and cisplatin in previously untreated inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2000; 23:60-64

[11] World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment. WHO offset publication No. 48. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1979

[12] Simon R. Optimal two-stage design for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1989; 10:1-10

[13] American Society of Clinical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15:2996-3018

[14] Lilenbaum RC, Langenberg P, Dickersin K. Single agent versus combination chemotherapy in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: a meta-analysis of response, toxicity, and survival. Cancer 1998; 82:116-126

[15] Rajkumar SV, Adjei AA. A review of the pharmacology and clinical activity of new chemotherapeutic agents in lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 1998; 24:35-53

[16] Gandara DR, Crowley J, Livingston RB, et al. Evaluation of cisplatin intensity in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III study of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 1993; 11:873-878

[17] Shepherd FA, Anglin G, Abratt R, et al. Influence of gemcitabine (GEM) and cisplatin (CP) schedule on response and survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet 1998; 17:472a

[18] Feliu J, Lopez GL, Madronal C, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine in non-small cell lung carcinoma patients age 70 years or older or patients who cannot receive cisplatin. Cancer 1999; 86:1463-1469

[19] Lorusso V, Mancarella S, Carpagnano F, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine in patients with stage IIIB-IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet 1998; 17:470a

[20] Esteban E, Llano JLG, Vieitez JM, et al. Phase I/II study of gemcitabine plus vinorelbine in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet 1998; 17:482a

[21] Isokangas OP, Mattson K, Joensuu H, et al. A phase II study of vinorelbine (VNR) and gemcitabine (GEM) in inoperable stage IIIB-IV NSCLC [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet 1998; 17:489a

[22] Lilenbaum RC, Schwartz MA, Cano R, et al. Gemcitabine (GEM) and navelbine (NVB) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet 1998; 17:494a

[23] Comella P, Frasci G, Panza N, et al. Cisplatin, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine combination therapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase II randomized study of the Southern Italy Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 1526-1534

[24] Ginopoulos P, Mastronikolis NS, Giannios J, et al. A phase II study with vinorelbine, gemcitabine and cisplatin in the treatment of patients with stage IIIB-IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer 1999; 23:31-37

Yuh-Min Chen, MD, PhD, FCCP; Reury-Perng Perng, MD, PhD, FCCP; Kuang-Yao Yang, MD; Tsang-Wu Liu, MD; Chun-Ming Tsai, MD; Jacqueline Ming-Liu, MD; and Jacqueline Whang-Peng, MD

(*) From the Chest Department (Drs. Chen, Perng, Yang, and Tsai), Veterans General Hospital-Taipei; School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan; and the Division of Cancer Research (Drs. Liu, Ming-Liu, and Whang-Peng), National Health Research Institute, Taipei, Taiwan.

Manuscript received August 30, 1999; revision accepted January 14, 2000.

Correspondence to: Jacqueline Whang-Peng, MD, Division of Cancer Research, c/o A191 ward, VGH-Taipei, Shih-pai Rd, Section 2, No. 201, Taipei, 112, Taiwan; e-mail: jqwpeng@ nhri.org.tw

COPYRIGHT 2000 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group