Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analog that is useful in the treatment of solid tumors. Its use has been postulated to produce lung injury by causing a capillary leak syndrome. We describe a gemcitabine-treated female patient who developed severe dyspnea, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, and hypoxia, with evidence of interstitial disease on pulmonary function tests. Following the administration of oral corticosteroids, she had complete resolution of all signs and symptoms of gemcitabine toxicity. Physicians should be aware of this treatable complication of gemcitabine therapy.

(CHEST 1998; 114:1 779-1 781)

Key words: capillary leak syndrome; corticosteroid therapy; gemcitabine; non-small cell lung cancer; pulmonary infiltrates

Abbreviations: PFT = pulmonary function test; RUL = right upper lobe

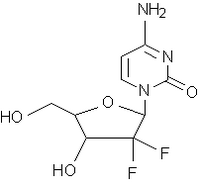

Gemcitabine (2',2'-difluoro-2'-deoxycytidine) is a nucleoside analog with activity against a number of solid tumors.[1,2] The pulmonary complications reported from its use range from self-limited episodes of bronchospasm to death from respiratory failure.[1-3] We describe the clinical course of a female lung cancer patient who developed dyspnea and interstitial infiltrates after treatment with gemcitabine, and her rapid recovery from gemcitabine toxicity after a brief course of oral corticosteroid therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 60-year-old woman was referred for evaluation of dyspnea on November 20, 1997. Approximately 8 months earlier, in March 1997, fine-needle aspiration material taken from a 7-cm lesion in her right upper lobe (RUL) had tested positive for non-small cell lung cancer; and a CT scan revealed an invasion of the mediastinal pleura by the primary tumor, right paratracheal adenopathy, and right middle lobe and right lower lobe nodules. The latter were confirmed as metastatic adenocarcinoma using open lung biopsy (stage IV, T3N2M1). The patient was treated with seven cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin from May 5, 1997 to September 3, 1997. There was an excellent response, with the tumor shrinking to approximately 2 cm. The patient developed a severe peripheral neuropathy, and her therapy was changed to gemcitabine. She received 5 weekly doses from September 24 through November 5, 1997. Each dose was 1,600 mg by IV piggyback (1,000 mg/[m.sup.2]). Following the fifth dose she developed a dry, hacking cough. One week later, she noticed dyspnea while climbing stairs. On November 19, she was seen by her oncologist, who ordered a chest radiograph, pulmonary function tests (PFTs), and a pulmonary consultation. In the pulmonary clinic she described her progression of symptoms: dyspnea at rest, tightness of chest, and a persistent, dry cough. She denied having fever, chills, or night sweats. She had no history of pulmonary disease prior to her lung cancer. She had never been a smoker and had no HIV risk factors. She was the director of a dance studio and had no history of exposure to pulmonary toxins. A purified protein derivative (tuberculin test) earlier in the year was negative. She had no history of cardiac disease. She had a history of herpes zoster involving the left leg, and a fractured vertebra and nasal septa from a 1990 motor vehicle accident. Her current medications were amitriptyline, 25 mg qd, and acyclovir, 400 mg bid. The remainder of her history was unremarkable. During her physical examination she appeared comfortable at rest. She was afebrile with a pulse rate of 100, a respiratory rate of 20, and a BP of 100/70. She had no jugular venous distention or use of accessory muscles. Fine basilar rales could be heard on auscultation. There was a normal [S.sub.1] and [S.sub.2], without murmurs or gallop. She had no peripheral edema. Her chest radiograph (Fig 1, left) revealed diffuse interstitial infiltrates, without evidence of cardiomegaly, adenopathy, or pleural effusion. PFTs performed that day showed a total lung capacity of 3.78 L (78% predicted), forced vital capacity of 2.06 L (69% predicted), and [FEV.sub.1] of 1.57 L (66% predicted), and a diffusing capacity of 9.03 mL/min/mm Hg (48% predicted). All were decreased since the original study of April 1997. Arterial blood gas results were pH, 7.45; Pa[O.sub.2], 37; and Pa[CO.sub.2], 53 (88% saturated).

[Figure 1 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

The patient declined admission for bronchoscopy. She instead began treatment with prednisone, 60 mg qd. At follow-up on November 24, she described near complete resolution of her cough. Her lung sounds were clear with auscultation. Her oxygen saturation was 100% at rest, with desaturation to 93% walking in the hallway. Her prednisone dosage was reduced to 40 mg qd, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis was started. At follow-up on December 8, 1997, her cough was gone, her lungs were clear, and she had no significant desaturation (99% to 98%) after climbing two flights of stairs. Her pulmonary infiltrates were also resolved (Fig 1, right). On PFTs, her forced vital capacity was 2.93 L (99% predicted) and her measured diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide was 14.65 mL/mm/mm Hg (78% predicted); both results had improved since her pretreatment studies of April 4, 1997. Prednisone therapy was tapered over the next 4 weeks and then discontinued. At follow-up on February 2, 1998, she had no complaints of respiratory symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analog with activity against a variety of solid tumors, including lung, breast, pancreas and ovary.[1] Dyspnea has been reported in 8% of patients, usually secondary to mild, self-limited bronchospasm.[1,2] In a trial of 40 patients with advanced breast cancer, 1 patient had dyspnea associated with pulmonary infiltrates on CT scan which improved after withdrawal of gemcitabine and initiation of corticosteroid therapy.[3] Pavlakis et al[1] described three patients in Australia with severe pulmonary toxicity. A woman with ovarian carcinoma and a man with large cell lung cancer developed diffuse interstitial pulmonary infiltrates and respiratory failure. At autopsy, both had evidence of respiratory distress syndrome with diffuse alveolar damage described. A third patient, who had ovarian cancer, had a similar presentation. Transbronchial biopsy revealed nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis. Gemcitabine was discontinued, and the patient improved after treatment with dexamethasone, 16 mg qd, before dying of the disease. The authors postulated that the pathogenesis was a capillary leak syndrome, such as that seen with another nucleoside analog, cytarabine. Cytarabine, also known as cytosine arabinoside or Ara-C, is similar structurally to gemcitabine. It can produce a syndrome of noncardiac pulmonary edema.[4,5] At autopsy, intense intra-alveolar proteinaceous edema is found, along with interstitial inflammation; and the findings may resemble ARDS.[5]

The diagnosis of drug-induced lung injury is one of exclusion. Our patient had symptoms, radiography, and pulmonary function tests compatible with diffuse interstitial lung disease. A bronchoscopy with biopsy was recommended to exclude the possibility of tumor or infection. However, the patient declined this intervention. Her rapid improvement on prednisone alone is inconsistent with progression of tumor or infection. It points to an inflammatory disease temporally related to the administration of gemcitabine. The absence of recurrence following completion of prednisone therapy, suggests that no environmental factors were involved. Given the paucity of data regarding gemcitabine toxicity, bronchoscopy would have been of great interest for both the histologic examination and the bronchoalveolar lavage to study the cell populations, protein content, and cytokines.

There appears to be a spectrum of clinical presentations with gemcitabine lung injury. Our patient was treated at an early stage, and she had a rapid recovery with no discernible sequelae. The two Australian patients who began treatment at an advanced stage died of respiratory failure despite corticosteroid therapy. Gemcitabine is becoming more widely used. It is important to recognize the syndrome of dry cough, progressive dyspnea, and interstitial infiltrates that appears within days following its administration, in order to intervene while the disease is still treatable.

REFERENCES

[1] Pavlakis N, Bell DR, Millward MJ, et al. Fatal pulmonary toxicity resulting from treatment with gemcitabine. Cancer 1997; 80:286-291

[2] Nelson R, Tarasoff P. Dyspnea with gemcitabine is commonly seen, often disease related, transient and rarely severe [abstract]. Eur J Cancer 1995; 31(suppl 15):s197-s198

[3] Carmichael J, Possinger K, Phillip P, et al. Advanced breast cancer: a phase II trial with gemcitabine. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13:2731-2736

[4] Cooper JAD, White DA, Matthay BA. State of the art: drug-induced pulmonary disease. Part I: Cytotoxic drugs. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986; 133:321-340

[5] Rosenow EC, Meyers JL, Swensen SJ, et al. Drug-induced pulmonary disease: an update. Chest 1992; 102:239-250

Nicholas J. Vander Els, MD, FCCP; and Vincent Miller, MD

(*) From the Pulmonary Service (Dr. Vander Els) and the Thoracic Oncology Service (Dr. Miller), Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and Cornell University Medical College, New York, NY.

Manuscript received April 20, 1998; revision accepted June 16, 1998.

Correspondence to: Nicholas J. Vander Els, MD, FCCP, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021; e-mail: vanderen@mskcc.org

COPYRIGHT 1998 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group