Drug therapy for depression

Goal:

To provide the pharmacist with the practical knowledge to recommend rational drug therapy for depression when appropriate.

Objectives:

After completing this lesson, the pharmacists should be able to: 1. Recognize the major adverse effects of the classes of antidepressant drugs. 2. Compare the newer antidepressants to the older ones. 3. Recommend correct dosing for antidepressant drugs. 4. Recognize symptoms of depression. 5. Identify certain drugs and medical conditions which may produce symptoms which mimic depression. 6. Recognize the time required before the onset of antidepressant drug effectiveness and the appropriate order in which depressive symptoms change during this response. 7. Recommend approaches for the management of antidepressant-induced side effects.

When I get depressed it seems to me as if I have fallen into a pit and I cannot get myself out. I wake up early in the morning, in the small hours, and I am overcome with despair. I am too worried and upset to go back to sleep, but at the same time, I am too listless and despondent to get up to do anything. I am frozen in unhappiness.

I feel helpless and troubled. I keep thinking about all the things that have gone wrong in my life, and I feel helpless to change anything now. This makes me utterly hopeless for the future, and my thoughts move on to how much better it would be for me and the world if I were to die.

I come to think of suicide, I even fantasize how I would do it: shoot myself? take an overdose? But my family would suffer: maybe I should make it look like an accident.

For days now, I have been so paralyzed in my thinking that I have not done any productive work. I just can't bring myself up to muster the energy, can't tackle what is in front of me. Then, at day's end, I feel even more like a failure.

I am exhausted but cannot rest, because these thoughts keep going around in my head. I get hungry but I don't have the appetite to eat a full meal, everything tastes flat, every swallow is an effort. When I am well, there are lots of things I enjoy doing, but when I get into my depression, when I am in the pit, nothing has any appeal for me.

The pharmacist should recognize the severity of depressive illness varies considerably. Depression exists in many forms. It may be defined as a mood, a symptom, a syndrome and an illness. Depression as a mood is a common, brief or long-lasting part of normal everyday living. Depression may be a presenting symptom of psychiatric or medical conditions. Depressive symptoms can be mimicked by some drugs (Table 1). Depression as a syndrome (set of symptoms) includes the list of symptoms found in Table 2. Depression as an illness may be viewed as a specific disease with a biochemical origin and consistent genetic patterns.

Table : Table 1: Drugs which may produce of exacerbate depression

Steroids: Oral contraceptives, corticosteroids, ACTH Anti-inflammatory agents and analgesics: Opiates, pentazocine,

indomethacin, phenylbutazone, ibuprofen Sedative-hypnotic agents: Barbiturates, benzodiazepines,

chloral hydrate, ethanol, ethchlovynol, glutethimide Antihypertensive and cardiovascular drugs: Resepine, alpha-methyldopa,

hydralazine, propranolol, digitalis, procainamide,

clonidine, guanethidine Miscellaneous: neuroleptics, stimulant withdrawal, amantadine,

levodopa, phenytoin, carbamazepine, anti-neoplastic

agents, baclofen

Table : Table 2: Symptoms od depression Psychological

Anhedonia (loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities;

loss of sex drive)

Dysphoric mood (despondent, sad, discouraged)

Excessive guilt

Pessimism, hopelessness, helplessness, self-pity

Social withdrawal

Physiological

Anorexia, weight loss

Loss of energy, fatigue

Psychomotor agitation or retardation

Sleep disturbances

Menstrual irregularities

Palpitations, constipation, headaches

Various non-specific somatic complaints

Cognitive

Decreased concentration and attention span

Confusion, poor memory

Slowed thought process

Delusions (persecutory, somatic or religious)

Suicidal ideation

Indecisiveness

Selection of a cycle

antidepressant

It is not clinically possible to identify by any biochemical means a specific type of depression and then select the cyclic antidepressant which would be best for that type of depression. Instead, drug selection is empirical, but certain guidelines for selection are recommended.

Selection of the antidepressant should be based on the desired degree of sedation or stimulant action for the patient. Many physicians would select a sedative antidepressant, such as amitriptyline or doxepin, due to the desired nighttime benefit in alleviation of insomnia. The antidepressant may be given at bedtime and the use of a hypnotic agent avoided. If the patient is withdrawn, apathetic, and sleeping too much, the physician may select a stimulating antidepressant such as fluoxetine or bupropion.

The patient response (or lack of it) to a particular antidepressant in a previous episode is helpful as a predictor. If the patient has benefited from a specific drug in the past it should again be therapeutic. The same principle applies usually to a lack of drug response.

The compatibility between patient susceptibility and side effect profile of the drug is very important. An elderly male may not be able to tolerate the anticholinergic effects (dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation) of some antidepressants. An antidepressant which does not produce weight gain (fluoxetine) or an orthostatic drop in blood (nortriptyline) may be more acceptable to some patients.

The proper selection of a cyclic antidepressant does not always guarantee a successful patient response. Errors in prescribing antidepressants do result in therapeutic failure. The two most common errors in prescribing are the failure to use adequate dosage and failure to continue treatment long enough. Table 3 provides dosage ranges and adverse effects for the currently available antidepressants. As a general rule, antidepressants treatment should be initiated by utilizing a divided dose regimen and gradually building to the desired level. The dose may then be converted to a single bedtime dose or a schedule which gives a portion of the drug during the daytime and the remainder at bedtime.

Table : [Tabular Data Omitted]

After the proper dose for the cyclic antidepressant has been achieved it is important to be aware of how the symptoms of depression change as a positive response to the drug. The first symptom to show improvement is usually a return to normal sleep pattern. Improvements appetite, nervousness, somatic complaints and motor activity will usually follow. In many cases, the patient is unaware of initial improvements but someone who is monitoring the response to therapy will notice. For most patients definite improvement can be seen within the first two to four weeks of treatment with adequate doses of the cyclic antidepressant. It is important to the person monitoring therapy to realize that a very rapid response may mean the patient has decided on suicide as a final solution to the problem.

Management of antidepressant-induced

side effects

Management of antidepressant-induced side effects is important for several reasons, chief among which is to enhance patient compliance. Compliance with medication regimens diminish as the incidence and severity of side effects increase. Physician (and pharmacist) discussion of side effects with the patient ma permit the administration of medication in doses most likely to be effective.

The following management techniques apply to individual patients who experience side effects as consequences of cyclic antidepressant treatment.

Anticholinergic effects

Dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention and constipation are anticholinergic effects from antidepressant blockade of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor.

Dry mouth management: Patient should be encouraged to use sugarless gum and hard candies to stimulate salivary flow. A 1-percent solution of pilocarpine used as a mouthwash three to four times a day will reverse cholinergic blockade and promote salivation. A 5 mg to 10 mg tablet of bethanechol dissolved sublingually will increase salivation. Bethanechol 10-30 mg po once to twice daily promotes salivation.

Blurred vision management: A 1-percent solution of pilocarpine drops, one drop QID improves vision by restoring pupil responsiveness. Bethanechol 10 mg to 30 mg po, TID is recommended but not as a first choice because of cholinergic excess (abdominal cramps, diarrhea, tremor, rhinorrhea, excess tearing).

Urinary retention management: Urinary hesitation without the presence of outflow obstruction can be treated with bethanechol (10 mg to 30 mg po TID). A more conservative approach would be to switch the patient to an antidepressant with less anticholinergic activity (desipramine, ludiomil, desyrel).

Constipation management: A bulk laxative or another hydrophilic preparation to soften and enlarge the stool is helpful. Cathartic laxatives (milk of magnesia) should be used only intermittently because use over prolonged periods can lead to decreased effectiveness and intestinal dysmotility.

Orthostatic hypotension

Nonpharmacologic management: Instruct the patient if the symptoms occur to rise slowly and carefully from a prone position, dangle feet for a full minute before attempting to stand. This should be done after long periods of lying down. Another useful method is the use of a footboard or other forms of exercise to strengthen calf muscles, which may prevent pooling of blood in the legs. Stockings or support hose have also been helpful.

Pharmacologic management: Selection of an agent with a low binding affinity for the alpha1-adrenergic receptor is a wise choice. Desipramine, fluoxetine, bupropion and protriptyline are examples. Nortriptyline has been reported to have a particularly low propensity to induce orthostatic hypotension. Giving the antidepressant at the lowest effective dose and in divided doses has been helpful in some cases.

Weight gain

Management: The patient who is gaining weight should be instructed to minimize fat and carbohydrate intake and adhere to a reasonable, regular exercise program. Edema may be treated by elevating the affected limbs or by the judicious use of a thiazide diuretic. Switching the patient to an agent which has not been reported to produce weight gain (fluoxetine, bupropion) may be required when a lack of compliance is a problem.

Any discussion of drug therapy for depression would not be complete without a review of the newer cyclic antidepressants. These agents are reviewed in terms of chemical structures, kinetics, dosing, and side effects.

Although it is not covered in the following discussion, Xanax (alprazolam) has been shown in some studies to be an effective antidepressant.

Wellbutrin (Bupropion)

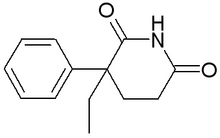

Bupropion is a monocyclic aminoketone, similar in structure to phenylethylamine and diethylpropion (Tenuate), which was approved 20 years ago as an anorectic agent.

Bupropion is an apparently effective antidepressant with an unknown mechanism of action. It is a weak blocker of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, but does inhibit the reuptake of dopamine to some extend. Bupropion does not inhibit monoamine oxidase.

Bupropion produces peak concentration within two hours with a biphasic decline. The half-life of the second phase (post-distribution) is 14 hours. Due to hepatic metabolism only a small portion of any oral dose reaches the systemic circulation intact.

Upon oral administration of 200 mg of bupropion, 87 percent of the dose was excreted in the urine and 10 percent in the feces. Several of the metabolites of bupropion are pharmacologically active but their potency and toxicity relative to bupropion is not known. Because two of these metabolites have longer half-lives their plasma concentration will be much higher than the bupropion concentration, articularly in long term use. This could attain clinical importance if these active metabolites accumulate.

Bupropion does induce its own metabolism in animals. If this autoinduction occurs in humans the relationship between concentration of bupropion and its metabolites to clinical effect could change with chronic use.

Bupropion initial dosing should begin at 100 mg po twice daily in the morning and early evening. This dose may be increased to 100 mg po three times per day no sooner than three days after starting therapy. After several weeks of 300 mg per day dosing the total daily dose may be increased to 450 mg but no individual dose should exceed 150 mg.

Bupropion is well tolerated in general, but the common side effects should be discussed. The ones that have occurred more commonly with bupropion than with placebo in the clinical trials are dry mouth, constipation, sweating, agitation, tremor, or shakiness.

The agitation seen in patients receiving bupropion report usually described as an inner restlessness or discomfort. It is not an objectively observable agitation. The patients receiving bupropion report feeling uncomfortable or restless inside.

Bupropion is associated with seizures in approximately 0.4 percent of patients treated at doses up to 450 mg per day. This incidence of seizures may exceed that of other marketed antidepressants by as much as fourfold. The estimated seizure incidence increases almost tenfold between 450 and 600 mg per day.

The risk of seizure appears strongly associated with dose and the present of predisposing factors. A history of head trauma or prior seizure, CNS tumor, concomitant medications that lower seizure threshold are all predisposing factors that were present in approximately 50 percent of the patients experiencing a seizure while receiving bupropion. any sudden and large increase in dose may also increase the risk.

Recommendations for reducing the seizure risks from bupropion are worth noting. The total daily dose should not exceed 450 mg. The daily those is administered three times daily with each single dose not to exceed 150 mg. The rate of dose increase is gradual.

Desyrel (trazodone)

Trazodone is a triazolopyridine that represents a new structural class of cyclic antidepressants. It is chemically and structurally unrelated to tricyclic, tetracyclic or other known antidepressants.

Trazodone has a mechanism of antidepressant action which is unclear. It does selectively block the reuptake of serotonin at the presynaptic neuronal membrane. This action may potentiate the action of serotonin. Trazodone may also have a dual effect on the central serotonergic system. In animals it acts as a serotonin agonist at high doses (6-8 mg/kg) while at low doses (0.05-1 mg/kg), it antagonizes the actions of serotonin. The uptake of dopamine or norepinephrine within the CNS do not appear to be influenced by trazodone.

Follow oral dosing. Trazodone is rapidly and almost completely absorbed from the GI tract. The rate and extent of absorption are influenced by the presence of foods. If trazodone is taken shortly after ingesting food there may be a slight increase in the amount of drug absorbed followed by a decrease in peak plasma concentration of the drug and a lengthening of the time to reach the plasma concentration. Peak plasma concentrations occur approximately one hour after oral administration when the drug is taken on an empty stomach or two hours after oral administration when taken with food. Steady-state plasma concentrations are usually attained within four days of multiple daily dosing (TID or BID) and exhibit wide interpatient variation.

Distribution of trazodone into human body tissues and fluids has not been determined. It does cross the blood-brain barrier in animals and brain concentrations are higher than plasma following the first eight hours of oral ingestion.

Trazodone is extensively metabolized in the liver via hydroxylation, oxidation and splitting of the pyridine ring. It is not known if any of the metabolites are active in humans.

Plasma concentrations of trazodone decline in a biphasic manner. Trazodone half-life in the initial phase is about three to six hours and the terminal phase half-life is five to nine hours.

Approximately 70 percent to 75 percent of an oral dose is excreted in urine within 72 hours of oral administration. The remainder of an oral dose is excreted in the feces.

The usual initial adult dose is 150 mg daily given in divided doses. This may be increased by 50 mg per day every three or four days depending on the patient's response and tolerance. For outpatients the maximum dose should not exceed 400 mg per day. Doses up to 600 mg per day may be needed for hospitalized patients.

The side effect profile of trazodone is found in Table 3. Priapism is a rare but potentially serious side effect. The incidence of trazodone-induced priapism is reported to occur between one in 1,000 and one in 10,000 male patients. This probably is a result of unusual alpha receptor sensitivity in susceptible male patients. This side effect (a prolonged painful erection) may require surgical intervention and can produce permanent impotence.

Prozac (Fluoxetine)

Fluoxetine hydrochloride is a new bicyclic antidepressant, substituted phenylpropylamine which is chemically unrelated to other antidepressants. Structurally related compounds include amphetamine (a stimulant), phenylephrine (a nasal decongestant), and diethylpropion (an appetite suppressant).

Fluoxetine is a more specific and potent competitive inhibitor of serotonin reuptake into the presynaptic terminal than any of the currently available cyclic antidepressants. This may be attributed to the long elimination half-life of fluoxetine and its active metabolite, norfluoxetine.

Fluoxetine has essentially no effect on norepinephrine or other neuro- transmitters. It has a weak affinity for binding to various neuroreceptors. Fluoxetine is well absorbed following oral administration. It may be given with or without food because the rate and the extent of absorption are not significantly affected by the absence or presence of food in the stomach. Fluoxetine is highly bound to plasma protein including albumin and alpha-1-glycoprotein. The degree of protein binding averages 94 percent. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine have detectable concentrations in the rat cerebral cortex, corpus striatum, hippocampus hypothalamus, brain stem and cerebellum. The apparent volume of distribution is very large. The volume of distribution exceeds body weight because of extensive tissue distribution and binding. Fluoxetine is demethylated hepatically to an active metabolite norfluoxetine, which is specific for inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin. Fluoxetine has a half-life of one to three days with norfluoxetine having a half-life of seven to 15 days. This long half-life makes once-a-day dosing possible but could pose a disadvantage because of an increased time for the drug to be excreted when undesirable side effects are present. Eighty percent of the drug is excreted in the urine and 15 percent is excreted in the feces.

Many of the cyclic antidepressants have a high frequency of anticholinergic and cardiovascular side effects. Fluoxetine has minimal to no anticholinergic or cardiovascular side effects, but does present certain common side effects. A review of 1,378 patients treated with fluoxetine showed nausea occurring in 25 percent of the patients. Other side effects were: nervousness (21 percent), insomnia (19 percent), headache (17 percent), tremor (16 percent), anxiety (15 percent), drowsiness (14 percent), dry mouth (14 percent), sweating (12 percent), and diarrhea (10 percent).

Because weight gain can be a troublesome side effect of antidepressants, the lack of weight gain with fluoxetine is a potential advantage. In clinical trials, weight loss was statistically but not clinically significant. This weight loss averaged only 1.2 kg among 333 patients.

The usual starting dose for fluoxetine is 20 mg per day given as a single dose in the morning. Fluoxetine can be given once daily because of its pharmacokinetic profile. Fixed dosage studies have demonstrated that the 20 mg dose is sufficient for most patients. Higher doses usually offer minimal or no additional efficacy. The starting dose of 20 mg per day may be slowly titrated to a maximum dosage of 80 mg per day may be slowly divided doses. A once-daily dosing regimen was compared to a BID regimen (morning and noon) and found no different in efficacy. The BID regimen did show a slight decrease in side effects. Afternoon and evening doses should generally be avoided because of the likelihood of producing insomnia.

If the patient requires a dosage of fluoxetine which is less than 20 mg per day, the pharmacist may dissolve the contents of one capsule in four ounces of water, Gatorade lemon-lime, apple juice, or Ocean Spray Cran-Grape juice. An aliquot of this may be given to produce the desired dose. A communication from the manufacturer states that this solution is stable for up to 14 days at room temperature or in the refrigerator. A five-minute standing time should be allowed after the initial mixing to allow for complete dissolution.

Suicide is a serious risk among all severely depressed patients. Suicide may be attempted with an overdose of antidepressant such as fluoxetine, which is not lethal when taken in overdosage attempts, is highly desirable.

Ludiomil (Maprotiline)

Maprotiline is a tetracyclic antidepressant which differs structurally from the monocyclic, bicyclic and tricyclic antidepressants.

Maprotiline blocks the reuptake of norepinephrine. It does not inhibit monoamine oxidase or appear to influence the reuptake of serotonin.

Maprotiline is slowly but completely absorbed from the GI tract. Peak plasma concentrations occur eight to 24 hours after a single oral dose. Roughly 88 percent of maprotiline is bound to plasma proteins. The drug and its metabolites are distributed to the liver, lungs, brain and kidneys with lower concentrations found in the adrenal gland, heart and muscle. The plasma half-life of maprotiline averaged 51 hours, with slow hepatic metabolism producing an active desmethylmaprotiline, which can undergo further transformation to an oxide metabolite. Roughly 60 percent of a dose of maprotiline is excreted in urine within 21 days, primarily as conjugated metabolites, and approximately 30 percent of the drug is excreted in feces.

Seizures have been reported in patients receiving maprotiline and have occurred principally in those patients with no history of seizures. It has been suggested (but not proven) that maprotiline may be associated with a higher incidence of seizures than the other cyclic antidepressants. Maprotiline-induced seizures have generally occurred in patients receiving doses of 200 mg or more daily. Rare seizures have occurred in patients receiving lower doses of the drug, generally during the early stages of therapy. Rapid dose increase and/or high plasma levels do not appear to be related to seizure occurrence. A special caution is warranted in patients with a history of seizures or who may be predisposed to seizures because of age, disease or injury.

The manufacturer suggests that the seizure risk may be decreased by initiating therapy with low doses. The initial dosage is usually 75 mg per day. This initial dose should be maintained for two weeks because of the long elimination half-life. Depending on the patient's response and tolerance this dose may gradually be increased in 25 mg increments. In most outpatients, a maximum dose of 150 mg per day will be effective. Doses as high as 225 mg per day may be needed in some patients. Doses of 225 mg per day should not be exceeded.

Bibliography Ayd FJ. Fluoxetine: An antidepressant

with specific serotonin

uptake inhibition.

Int Drug Therapy Newsletter,

1988; 23:5 - 11. Bryant SG, Ereshefsky L.

Antidepressant properties

of trazodone. Clinical

Pharmacy, 1982; 1:406 - 17. Cohen BM, Harris PQ, Altesman

RI, Cole JO. Amoxapine:

neuroleptic as well as

antidepressant? Am J Psychiatry,

1982; 139:1165 - 7. Cole JO, Schatzberg AF, Sniffin

C et al. Trazodone in

treatment resistant depression:

An open study. J Clin

Psychopharm, 1981; 1:49 - 54. Dessain EC, Schatzberg AF,

Woods BT, Cole JO. Maprotiline

treatment in depression,

a perspective on seizures.

Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1986; 43:86 - 90. Dornseif BE, Dunlop SR, Potvin

JH, Wernicke JF. Effect

of dose escalation after

low-dose fluoxetine therapy.

Psychopharm Bulletin,

1989; 25:71 - 9. Dugas JE, Weber SS. New

drug evaluations: Amoxapine.

Drug Intelligence and

Clinical Pharm, 1982;

16:199-204. Gershon S, Mann J, Newton

R, Gunther. Evaluation of

trazodone in the treatment

of endogenous depression:

Results of a multicenter

double-blind study. J Clin

Psychopharm, 1981;

1:395-445. Fawcett J, Edwards JH, Kravitz

HM, Jeffriess H. Alprazolam:

An antidepressant?

Alprazolam, desipramine,

and an alprazolam-desipramine

combination in the

treatment of adult depressed

outpatients. Jr Clin

Psychopharmacology,

1987; 7:295 - 310. Hisrich KR, Bennett JA.

Fluoxetine. Jr Pharm

Tech, 1987; 3:219 - 22. Lydiard RB, Gelenberg AJ.

Amoxapine - an antidepressant

with some neuroleptic

properties? Pharmacotherapy,

1981; 1:163 - 178. Nies A. Differential response

patterns to MAO inhibitors

and trycytics. J Clin Psychiatry,

1984; 45:70 - 7. Overal JE, Biggs J, Jacobs M,

Holden K. Comparison of

alprazolam and imipramine

for treatment of outpatient

depression. J Clin Psychiatry,

1987; 48:15 - 9. Rickels K, Chung HR, Caanalosi

IB, Hurowitz AM et al.

Alprazolam, diazepam,

imipramine, and placebo in

outpatients with major depression.

Arch Gen Psychiatry,

1987; 44:862 - 66. Rickels KS, Smith WT, Blandin

V. Comparison of two

dosage regimens of fluoxetine

in major depression. J

Clin Psychiatry, 1985;

3:38 - 41. Sommi RW, Crismon ML,

Bowden CL. Fluoxetine: A

serotonin-specific second-generation

antidepressant.

Pharmacotherapy, 1987;

7:1 - 15. Stimmel GL. New drug evaluations:

Maprotiline. Drug

Intelligence and Clinical

Pharm, 1980; 14:585-90. Wells BG, Gelenberg AJ.

Chemistry, pharmacology,

pharmacokinetics, adverse

effects and efficacy of the

antidepressant maprotiline

hydrochloride. Pharmacotherapy,

1981; 1:121 - 39. Wernicke JF. The side effect

profile and safety of fluoxetine.

J Clin Psychiatry,

1985; 3:59 - 67.

COPYRIGHT 1990 Reproduced with permission of the copyright holder. Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without permission.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group