We recently evaluated a cluster of cases of disseminated coccidioidomycosis referred to the Naval Medical Center San Diego. Between March and June of 2002, seven cases were diagnosed and treated. In a 5-year record review (March 1997-February 2002), we found only seven cases of disseminated disease attributable to Coccidioides immitis at the same institution. This report of seven cases over a 3-month period represents a 20-fold increase in the number of complicated C. immitis infections. All cases were non-Caucasians, had disseminated disease to bone and/or skin without meningeal involvement, and had a delay of 1.5 to 6 months from symptom onset until the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. Four of our cases occurred in previously healthy, young active duty members, emphasizing the importance of this mycosis in U.S. military personnel.

Introduction

Coccidioides immitis is a pathogenic fungus endemic to the lower Sonoran zone of the southwestern United States, including California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Texas, and Utah. An increasing number of cases within California have been recognized over the past 2 decades, most notably in 1991 to 1992.1 The rise in incidence of this fungal disease may be related to the increasing population density, the increasing prevalence of immunosuppressed patients who are at risk for complicated disease, and travel to endemic areas.2,3 Currently, 350,000 military members are stationed within endemic areas, and additional personnel perform temporary training exercises in these areas.4

Acute coccidioidomycosis is usually asymptomatic. Those who have symptoms typically present with a self-limited "flu-like" illness; a small proportion develops pneumonia. Disseminated disease is estimated to occur in less than 1% of persons but is more likely in those with a T-cell immunodeficiency or in non-Caucasians.5-7 Disseminated disease may exhibit protean manifestations including skin, bone, and central nervous system involvement.

We present seven cases of disseminated coccidioidomycosis that presented to Naval Medical Center San Diego with skin and/or bone lesions from March to June of 2002 (Table I). Cases were diagnosed using both enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and complement fixation (CF) titers as well as histopathologic and culture results. All cases resided in cities and military bases located in southern California (Fig. 1).

Case Reports

Case 1

A 22-year-old African American male air traffic controller from the Naval Air Station (Lemoore, California) presented to the Naval Medical Center San Diego with a 3-month history of non-healing skin lesions of his right shoulder and right ankle. These lesions had been incised and drained in February 2002; routine bacterial cultures of the purulent drainage were negative. After several courses of empiric antibiotics, the lesions became nonpurulent but persisted as clean-based ulcers (Fig. 2). The patient noted a 3-month history of involuntary 7-kg weight loss and lower back pain. He also reported having developed a radiographically confirmed pneumonia 6 months previously that had resolved without specific therapy.

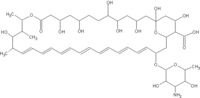

He was referred to the Naval Medical Center San Diego in May 2002 for a suspected immunodeficiency. He had a white blood count of 6,800/mm^sup 3^ and a negative human immunodeficiency virus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. A coccidioidomycosis EIA was IgG and IgM positive with a CF titer of 1:512. Skin biopsy of his ankle lesion revealed granulomatous dermatitis with typical coccidioidal spherules and grew C. immitis in culture. A bone scan revealed lesions in the C1 and T9 vertebral bodies, right distal clavicle, right calcaneus, and two areas in the parietooccipital skull (Fig. 3). Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine showed T8-T12 and S1 bony lesions with soft tissue involvement enveloping these vertebral bodies as well as bony and soft tissue involvement at C1, C2, and C6. The patient was diagnosed with disseminated coccidioidomycosis and is slowly improving on a lipid formulation of amphotericin (Abelcet, 5 mg/kg daily).

Case 2

A 21-year-old African American male stationed at the Naval Air Station (Miramar, California) developed severe lower back pain in November 2001. Two weeks earlier he noted a "flu-like" illness with drenching night sweats and fevers. He was evaluated for lower back pain in late November and December, diagnosed with lumbar spasm, and treated with pain medications and physical therapy.

The back pain persisted, and he was seen at a New York hospital while on leave in January 2002. In addition to back pain, the patient reported an involuntary weight loss of approximately 18 kg. Magnetic resonance imaging of his vertebrae revealed a L4 lesion with an epidural abscess as well as a C6 lesion. A thoracic/abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 1.5-cm right upper lobe cavity, multiple 1- to 2-mm right-sided lung nodules, enlarged Mar lymph nodes, and splenic lesions. The patient was suspected to have malignancy, tuberculosis, or coccidioidomycosis. Because of extensive bone destruction and epidural abscess at L4, he underwent surgical debridement of this area including an L4 vertebrectomy with humeral bone grafting. Cultures from this procedure grew C. immitis, and the CF titer was 1:128. He received approximately 2 g of Abelcet and is currently receiving oral itraconazole solution, 200 mg twice daily. He continues to have back pain in the surgical area and is being medically retired.

Case 3

A 59-year-old Hispanic female residing in Fresno, California developed pneumonia in November 2001. She was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Her pulmonary symptoms resolved over the next 6 weeks, but she noted painful "blisters" on her hands, breasts, and trunk. She also noted the onset of night sweats, fatigue, cephalgia, and a 13.6-kg weight loss. She was diagnosed with possible mycosis fungoides or a metastatic carcinoma. A CT scan of the chest showed a left upper lobe nodule with mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and a bone scan showed multiple skull lesions. A lung biopsy of the nodule and a skin biopsy of one of the blisters showed granulomatous dermatitis with negative routine bacterial cultures.

Upon referred to our hospital in March 2002, a skin biopsy of a blister on her trunk revealed C. immitis spherules. A coccidioidomycosis EIA was IgM and IgG positive with a CF titer of 1:256. The patient was treated with 5 mg/kg daily of Abelcet for 2 weeks at which time she developed an extensive deep venous thrombus of her right arm requiring removal of the peripherally inserted central catheter line. As a result of the patient's refusal to accept further parenteral medications, Abelcet was discontinued, and she was given itraconazole oral solution, 200 mg twice daily. Her skin lesions are slowly healing but are still present after 4 months of therapy.

Case 4

A previously healthy 21-year-old African American male stationed at Fort Irwin presented in September 2001 with fevers and cough. He was diagnosed with pneumonia by chest radiograph and was treated with oral antibiotics. He initially improved, but 6 months later (March 2002), he presented with cough, night sweats, fevers to 104[degrees]F, and right-sided chest pain. A repeat chest radiograph showed a diffuse interstitial miliary infiltrate. On physical examination, he had a right breast mass that was biopsied and demonstrated C. immitis. His serum CF titer was 1:1,024. A bone scan demonstrated intense activity in the cervical spine, thoracic spine, and left pelvis. A CT scan demonstrated a large cystic mass at the T5 vertebra that laterally displaced the aorta, bony destruction of the left anterior fourth rib, and a large pelvic sidewall mass eroding the left hemisacrum.

The patient was treated with 5 mg/kg daily of Abelcet. After 1 month of therapy, his CT scan demonstrated enlargement of the thoracic vertebral lesions, and his CF titers remained elevated at 1:1,024. Given the failure to improve, he underwent surgical resection of the thoracic vertebral lesion and is currently receiving both Abelcet and oral itraconazole.

Case 5

A 24-year-old Filipino active duty male from the Marine Corps base, Camp Pendleton, California presented with fever and cough. He was diagnosed with right upper lobe pneumonia in October 2001 and was given levofloxacin with symptom resolution. Within the next month, he developed skin nodules on his left ear lobe, left cheek, and midline of his back. The largest lesion was on his back and measured 2.5 x 1.5 cm with a central ulceration. A skin biopsy grew C, immitis, and the pathology showed coccidioidal spherules. A C. immitis EIA was positive for both IgM and IgG; a CF titer was 1:16. The patient was treated on oral fluconazole 800 mg daily with good response. He is currently working full-time on active duty military service.

Case 6

A 19-year-old Filipino male residing in the San Diego area (Chula Vista) noted paresthesias in his left hand in January 2002. Over the next 2 months, he developed swelling on the dorsal aspect of his hand. He denied antecedent trauma to his hand. A hand radiograph in March was unremarkable. The patient continued to have a swollen hand, and in early June, he developed erythema and a fluctuant area on the dorsum of his hand, prompting him to report to our emergency room. The hand lesions were incised and drained expressing purulent material; he was empirically treated with intravenous cefazolin. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left hand showed osteonecrosis of the middle and ring fingers proximal to the metacarpal bones. Cultures of the hand grew C. immitis, and the pathology showed granulomatous inflammation with spherules. A bone scan showed uptake in the left wrist area, distal left clavicle, and skull. A C. immitis enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was IgM and IgG positive, and his CF titer was 1:256. He is currently being treated with 1 mg/kg daily of amphotericin B.

Case 7

A 17-year-old African American male student in Chula Vista noted right ankle pain beginning in April 2002. He denied antecedent trauma, and foot radiographs were normal. The pain persisted, and 6 weeks later, he noted a nodule on his right medial malleolus. This area expanded to an erythematous 3 x 3-cm lesion over the next 2 weeks. A repeat radiograph showed a 2 x 2-cm erosion of the right navicular bone, and he was diagnosed with probable bacterial osteomyelitis. During debridement, 3 cc of purulent material was drained, devitalized bone was resected, and the patient was empirically treated with clindamycin. A bone scan showed increased uptake of the right ankle, midfoot, and knee; his chest radiograph was clear. On day 5, C. immitis was noted on fungal cultures, and the patient was started on Abelcet. His CF titer was 1:64. He is currently receiving 5 mg/kg daily of Abelcet and is scheduled to receive a navicular bone graft.

Discussion

Coccidioidomycosis, also referred to as Valley Fever or Desert Fever, is an endemic mycosis of the southwestern United States acquired through the inhalation of airborne fungal elements called arthroconidia. Activities that lead to dust formation increase the risk for infection. Natural events such as earthquakes and dust storms have been linked to outbreaks.8,9 Human activities such as archaeological digs, construction work, and military training exercises have been associated with C. immitis infections.10-12 Several previous reports have demonstrated that coccidioidomycosis is an occupational hazard for military personnel;5,6,12-15 the first reported case of this disease occurred in an Argentinean soldier.16 Smith et al.5 reported that 8% to 25% of military members training in endemic areas during World War II were infected annually. Hooper et al.17 evaluated Marine Corps members stationed at Twenty-Nine Palms and found skin test conversion rates as high as 50% during a 6-month period in 1978; the incidence of coccidioidomycosis in military personnel has not been recently studied.

Four outbreaks of C. immitis infection in military personnel have been reported in the literature. During World War II, an epidemic of 75 cases of symptomatic pulmonary disease was reported. This outbreak was associated with vehicles that created excessive dust.18 In 1977, 18 cases occurred at the Lemoore Naval Air Station due to a dust storm. Several of these cases involved military members, including four cases of disseminated disease.9 Standaert et al.12 published an outbreak of coccidioidomycosis occurring in a U.S. Marine reserve unit from Tennessee performing military maneuvers at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Lompoc, California. This 3-week training exercise consisting of marching and digging in the soil resulted in 8 of 27 (30%) men developing acute coccidioidomycosis. Most recently, 10 of 22 (45%) U.S. Navy Seals undergoing sniper training in Coalinga, California developed acute C. immitis infection.13

C. immitis causes both self-limited infections that may lead to missed workdays, as well as complicated disease, which may result in substantial permanent disability and forced military retirements. Rush et al.14 reported 126 cases of C. immitis from 1983 to 1987 at Air Force clinics in California, Arizona, and Texas; 50% were in active duty members, and approximately 30% had disseminated disease. Oison et al.15 reported three military personnel with disseminated disease, two of which were eventually medically retired.

Despite our extensive previous experience with sporadic coccidioidomycosis, we were concerned by the seven recently identified cases of aggressive disseminated coccidioidomycosis in our clinic. These cases over a brief period represent a 20-fold increase in the number of complicated cases. The number of coccidioidomycosis cases in California-and in the San Joaquin Valley in particular-has reportedly increased steadily over the past decades with sharp increases often temporally associated with weather patterns and natural disasters.8,9 The reason(s) for the rise in the number of complicated cases in our clinic is unclear. None of the patients were immunocompromised or reported typical high-risk activities preceding the onset of their symptoms. All cases resided in known endemic areas widely across southern California, and all were non-Caucasians.

Non-Caucasian ethnicity has been reported as a risk factor for disseminated disease. Filipinos and African Americans have been shown to have up to a 200-fold increased risk of disseminated disease and an increased mortality rate.7 In addition, Hispanics, Native Americans, and non-Filipino Asians have a higher risk than Caucasians. This racial predisposition has also been demonstrated in military populations.6,14 The reason that certain ethnicities have a predisposition for more severe disease is uncertain; however, certain human leukocyte antigen types have been implicated.19

The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis should be entertained in persons residing or traveling from endemic areas. Although pulmonary manifestations are more common, nonhealing skin lesions or bony lesions, particularly in non-Caucasians, should prompt consideration of coccidioidomycosis. The manifestations of this disease are protean and may imitate other granulomatous diseases or malignancy; therefore, a high index of suspicion is necessary. The diagnosis can be made serologically using an EIA screen with CF confirmation. In addition, cultures may yield a typical white mold within 4 to 14 days. Histopathologic specimens often reveal granulomas, sometimes with classic C. immitis spherules. Prompt diagnosis is essential for the management of complicated coccidioidomycosis.

Treatment of disseminated disease relies upon amphotericin B or lipid formulations of amphotericin such as Abelcet or Ambisome. After treatment with amphotericin, an azole such as fluconazole or itraconazole is typically used. Itraconazole appears superior to fluconazole for cases with bone involvement.20,21

Summary

The increasing incidence of coccidioidomycosis in California is alarming. Our cluster of aggressive disseminated cases among previously healthy persons highlights the potential impact of this disease. All of our cases had delayed diagnoses, emphasizing that clinicians should entertain this diagnosis in those residing in or traveling to endemic areas. Cases often present after personnel leave an endemic area; this is particularly important given the mobility of military forces. Ethnicity appears to be a significant factor in the severity of coccidioidomycosis with a much higher rate of disseminated disease in non-Caucasians.

This report emphasizes the military relevance of coccidioidomycosis, a disease that may cause substantial disability and medical retirements. Given this case cluster and other reported outbreaks of coccidloidomycosis in military members, a case registry within the military might be helpful in disease surveillance. Furthermore, incidence studies in high-risk personnel would be useful to determine whether further preventative actions are needed to limit disease occurrence in military personnel. The ultimate prevention strategy would be the development of a coccidioidal vaccine. Education of troops and clinicians regarding this mycosis is essential in establishing an early diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis before progressive disease develops.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Judy Christensen for the graphics contained in this article.

References

1. Pappagianas D: Marked increase in cases of coccidloidomycosis in California: 1991, 1992, and 1993. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 19: S14-8.

2. Kirkland TN, Fierer J: Coccidioidomycosis: a reemerging infectious disease. Emerg Infect Dis 1996; 3: 192-9.

3. Galgiani JN: Coccidioidomycosis: a regional disease of national importance: rethinking approaches for control. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 293-300.

4. Olivere JW, Meier PA, Fraser SL, Morrison WB, Parsons TW, Drehner DM: Coccidioidomycosis: the airborne assault continues: an unusual presentation with a review of the history, epidemiology and military relevance. Aviat Space Environ Med 1999; 70: 790-6.

5. Smith CE, Bear RR, Rosenberger HG, Whiting EG: Effect of season and dust control on Coccidioidomycosis. JAMA 1946; 132: 833-8.

6. Gray GC, Fogly EF, Albright KL: Risk factors for primary pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis hospitalizations among United States Navy and Marine Corps personnel, 1981-1994. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998; 58: 301-12.

7. Rosenstein NE, Emery KW, Werner SB, et al: Risk factors for severe pulmonary and disseminated Coccidioidomycosis: Kern County, California, 1995-1996. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32: 708-15.

8. Schneider E, Hajjeh RA, Spiegel RA, et al: A Coccidioidomycosis outbreak following the Northridge, California, earthquake. JAMA 1997; 277: 904-8.

9. Williams PL, Sable DL, Mendez P, Smyth LT: Symptomatic Coccidioidomycosis following a severe natural dust storm: an outbreak at the Naval Air Station, Lemoore, California. Chest 1979; 76: 566-70.

10. Werner SB, Pappagianis D, Heindl, Mickel A: An epidemic of Coccidioidomycosis among archeology students in northern California. N Engl J Med 1972; 286: 507-12.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Coccidioidomycosis in workers at an archeologic site: Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, June-July 2001. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001; 50: 1005-8.

12. Standaert SM, Schaffner W, Galgiani JN, et al: Coccidioidomycosis among visitors to a Coccidioides immifis-endemic area: an outbreak in a military reserve unit. J Infect Dis 1995; 171: 1672-5.

13. Crum NF, Lamb C, Utz G, Amundson D, Wallace M: Coccidioidomycosis outbreak in Navy Seals during training in an endemic area: Coalinga, California. J Infect Dis 2002; 186: 856-8.

14. Rush WL, Dooley DP, Blatt SP, Drehner DM: Coccidioidomycosis: a persistent threat to deployed populations. Aviat Space Environ Med 1993; 64: 653-7.

15. Olson PE, Bone WD, LaBarre RC, et al: Coccidioidomycosis in California: regional outbreak, global diagnostic challenge. Milit Med 1995; 160: 304-8.

16. Posada A: Uno Nuevo caso de micosis fungoidea con psorospermias. Ann Circulo Medico Argentino 1892; 15: 585-96.

17. Hooper R, Poppell G, Curley R, Husted S, Schillaci R: Coccidioidomycosis among military personnel in Southern California. Milit Med 1980; 145: 620-3.

18. Goldstein DM, Louie S: Primary pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis. War Med 1943; 4: 299-317.

19. Louie L, Ng S, Hajjeh R, Johnson R, et al: Influence of host genetics on the severity of Coccidioidomycosis. Emerg Infect Dis 1999; 5: 672-9.

20. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Catanzaro A, Johnson RH, Stevens DA, Williams PL: Practice guidelines for the treatment of Coccidioidomycosis: Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 30: 658-61.

21. Galgiani JN, Catanzaro A, Cloud GA, et al: Comparison of oral fluconazole and itraconazole for progressive, nonmeningeal coccidioidomycosis: a randomized, double- blind trial Mycosis Study Group. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133: 676-86.

Guarantor: LCDR Nancy F. Crum, MC USNR

Contributors: LCDR Nancy F. Crum, MC USNR; LT Edith R. Lederman, MC USNR; CDR Braden R. Hale, MC USNR; LCDR Matthew L. Lim, MC USNR; CAPT Mark R. Wallace, MC USN

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Jun 2003

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved