Kuffer EK, Dart RC, Bogdan GM, Hill RE, Caper E, Darton L. Effect of maximal daily doses of acetaminophen on the liver of alcoholic patients. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161:2247-2252.

* PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

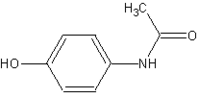

Acetaminophen in doses of 4 g/d did not affect liver function of alcoholic patients in this randomized study.

These results do not rule out the possibility of acetaminophen-induced liver failure in alcoholic patients, especially patients with pre-existing liver disease or those who continue to drink. Patient-oriented outcomes (ie, studying chronic acetaminophen use in alcoholics to determine the incidence of developing hepatic failure) ultimately would resolve this controversy.

However, these data do cast doubt on the medical myth (based on case reports) that acetaminophen use in alcoholics causes hepatotoxicity.

* BACKGROUND

Traditionally, acetaminophen use in alcoholics has been discouraged due to uncontrolled retrospective data (mostly case reports) that suggest drug-induced hepatotoxicity with therapeutic doses.

However, other available analgesic therapy options in alcoholic patients are limited. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with much more common adverse gastrointestinal effects in this population, and opiate analgesic use incurs a risk of substance abuse. This study evaluated the effect of the short-term administration of full doses of acetaminophen on liver function in alcoholic patients.

* POPULATION STUDIED

This study included 201 alcoholic patients at least 18 years of age who had entered an alcohol detoxification facility in Denver, Colorado. Patients were excluded if baseline laboratory values were abnormal (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] or alanine aminotransferase [ALT] levels >120 U/L, international normalized ratio [INR] >1.5, or serum acetaminophen concentration >20 mg/L), if they had a history of ingesting more than 4000 mg/d of acetaminophen within 4 days of enrollment, an allergy to acetaminophen, were enrolled in any other trial within the previous 3 months, or were intoxicated with alcohol at the time the first dose of study medication was administered.

This patient population represented alcoholics in primary care who did not have evident liver dysfunction and had very recently stopped drinking.

* STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY

This was a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Allocation to treatment group (determined with computer software) was concealed from the investigator involved with patient evaluations and care.

Acetaminophen, 1000 mg, or an identical placebo was administered orally 4 times daily for 2 consecutive days. Laboratory studies (acetaminophen concentration, AST, ALT, [gamma]-glutamyl transferase, and INR) were evaluated at baseline and on days 2 and 4. Alcohol concentrations were determined at initial presentation with the use of a breath alcohol analyzer. Patients were classified into 1 nutrition category (normal nutrition status, mild malnutrition, moderate malnutrition, or severe malnutrition), and body mass index was calculated.

This was a well-designed study. Appropriate disease-oriented outcomes (changes in liver function tests) were evaluated. The selected acetaminophen regimen represents maximum daily dosing and the recommended first-line treatment of chronic pain conditions (eg, osteoarthritis).

Just after an alcoholic stops drinking (with negative serum ethanol serum concentrations) is when conversion of acetaminophen to its potentially hepatotoxic metabolite is highest. Therefore, the time of acetaminophen dosing in this study represented the period of greatest vulnerability. However, results apply only to short-term acetaminophen use in alcoholics without evident liver dysfunction. Alcoholic patients commonly seen in primary care may require acetaminophen therapy longer than 2 days.

* OUTCOMES MEASURED

The primary outcomes measured were changes in liver function tests (AST, ALT, and INR) at baseline, 2 days after acetaminophen use, and 2 days after stopping acetaminophen.

* RESULTS

Overall, 102 patients randomized to receive acetaminophen and 99 patients randomized to receive placebo completed the study. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic or baseline laboratory values between groups. Mean AST, ALT, and INR values did not differ between groups. Time-dependent changes in INR were not seen (P=.07).

Four patients in the acetaminophen group and 5 in the placebo group developed AST or ALT values greater than 120 U/L, but no values in any patient went above 200 U/L. The highest individual aminotransferase (197 U/L) and INR (1.75) values occurred in the placebo group. Post hoc subgroup analysis showed no increase in liver function among patients with low body-mass indexes or in patients classified as malnourished.

Joseph J. Saseen, PharmD, Departments of Clinical Pharmacy and Family Medicine, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, E-mail: joseph.saseen@uchsc.edu.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group