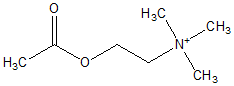

INTRODUCTION: Treatment strategies for Myasthenia gravis (MG) are directed at reducing acetylcholine receptor antibody production (immunosuppression, thymectomy, corticosteroids) and increasing availability of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Pyridostigmine bromide (PB) is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor used to treat MG. Toxicity from PB overdose has focused on cholinergic toxicity, but bromide toxicity (bromism) can be underappreciated. We present one of the first reported pediatric cases suspicious for bromism from PB use.

CASE PRESENTATION: A 22-month-old male with a history of MG presented to the emergency department with bradycardia and respiratory distress. He was in his usual state of health and feeding normally at home when he developed increased salivation and difficulty breathing. There was no report of choking or coughing surrounding the dyspnea. At home when he became ashen, emergency medical services was activated and CPR was initiated. Upon arrival, paramedics noted bradycardia and respiratory arrest. On hospital presentation, he was bradycardic (pulse = 30), breathing shallow and had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3. There was no evidence of increased lacrimation, excessive urination, miosis, diarrhea, nor emesis. He was intubated after receiving atropine, etomidate and rocuronium. Heart rate increased transiently after intubation; however, bradycardia returned after 30 minutes. A chemistry panel revealed an elevated chloride level of 121 mEq/L with a low anion gap of 3. A bromide level obtained two days after presentation was elevated at 14 mg/dL (normal <0.5 mg/dL). Clinical course was significant for 3 days of persistent CNS depression. Head CT was within normal limits. Past medical history was significant for MG diagnosed 5 months prior to admission for persistent ptosis and difficulty holding his head upright. His evaluation included an abnormal tensilon test and an elevated" serum acetylcholine receptor antibody titer. PB therapy was initiated with partial improvement in weakness and ptosis. Thymectomy was performed 2 months prior to admission. Due to persistent symptoms, PB doses were increased independently by ophthalmology and neurology.

DISCUSSIONS: Signs of cholinergic toxicity include diarrhea, excessive

urination, miosis, bradycardia, emesis, lacrimation and salivation. Our patient displayed two of these, but also displayed evidence of CNS depression; a sign not typically associated with cholinergic crisis. Furthermore, pyridostigmine does not readily cross the blood Drain barrier, thus raising concerns for another factor to account for the CNS depression. Our suspicion for bromism stemed from the high chloride level of 121 mEq/L with a low anion gap. Many hospital laboratories utilize electrolyte panels that interpret halide ions as chloride; therefore, an elevated bromide level would be falsely reported as an elevated chloride level. If we approximate a normal chloride level of 110 mEq/L then 11 mEq of Bromide could be present. This level translates into a toxic level of 88 mg/dL (toxic level > 50 mg/dL). Unfortunately, a specific bromide level was not measured until after two days of resuscitation with normal saline and maintenance of brisk urine output, maneuvers that increase excretion of bromide. Bromism has previously been associated with pyridostigmine [1]. To our knowledge, this is the first reported suspicious case occurring in a child. In cases of long-term exposure to PB, such as treatment for MG, bromism should be considered in the differential diagnosis; especially when the clinical picture is not one of typical cholinergic toxicity. Clinical suspicion and prompt laboratory confirmation can assist in establishing inpatient treatment plan and on-going pyridostigmine treatment. Other agents are available that are not complexed with bromide and may present a viable alternative.

CONCLUSION: Bromide toxicity should be considered in patients on PB who present with depressed mental status.

REFERENCE:

[1] Rothenberg, D.M., et al., Bromide intoxication secondary to pyridostigmine bromide therapy. Jama, 1990. 263(8): p. 1121-2.

DISCLOSURE: Aaron Godshall, None.

Aaron J. Godshall MD * Cyrus Rangan MD John T. Li MD Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, Long Beach, CA

COPYRIGHT 2005 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group