If early treatment fails, patients should be referred to pain clinics

Shingles, or herpes zoster, may occur at any stage in a person's life. Herpes zoster is the clinical manifestation of the reactivation of a lifelong latent infection with varicella zoster virus, usually contracted after an episode of chickenpox in early life.[1] Varicella zoster virus tends to be reactivated only once in a lifetime, with the incidence of second attacks being [is less than] 5%.[2] Herpes zoster occurs more commonly in later life (as T cell immunity to the virus wanes) and in patients who have T cell immunosuppression.

Pain persisting after herpes zoster, termed postherpetic neuralgia, is the commonest and most feared complication. Its definition is controversial, ranging from pain persisting after the rash heals to pain persisting 30 days or 6 months after the onset of herpes zoster. Some experts consider all pain during and after herpes zoster as a continuum. Therefore we have suggested that this total duration of pain and pain at a single time point (3 months after onset) be used as endpoints in clinical studies.[3] Post-herpetic neuralgia is associated with scarring of the dorsal root ganglion and atrophy of the dorsal horn on the affected side, which follows the extensive inflammation that occurs during herpes zoster. These and other abnormalities of the peripheral and central nervous system produce the pain and other unpleasant symptoms of post-herpetic neuralgia, which include allodynia (pain occurring in response to normally innocuous stimuli), and hyperalgesia.[4]

It is not known why herpes zoster recurs so infrequently compared with recurrent genital herpes, when the latter is caused by the herpes simplex virus which is similar in pathogenesis. Is it because varicella zoster virus is latent in both neurones and satellite cells in the dorsal root ganglia whereas herpes simplex virus remains latent within the neurones alone. Why does extensive inflammation of nerves and prolonged pain develop rather than just parasthesiae in recurrent herpes simplex? Why is post-herpetic neuralgia common in elderly people but not in immunocompromised patients where only the incidence of herpes zoster increases? Discovering the answers to these questions is essential to improving therapeutic strategies.

Recently, the introduction of two new antiviral drugs for herpes zoster, famciclovir and valaciclovir, stimulated several large multicentre clinical trials that identified which patients with herpes zoster are most likely to develop post-herpetic neuralgia.[5-7] The risk of post-herpetic neuralgia increases with age--particularly in people over the age of 50--and it also increases if patients have severe pain or severe rash during the acute episode or if they have a prodrome of dermatomal pain before the rash appears. Unfortunately, in most of these trials the severity of pain was measured only during the acute episode, and follow up ceased after six months.

In this issue of the BMJ, Helgason et al (p 794) report the results of their study of the first episode of herpes zoster in 421 patients seen by 62 general practitioners in Iceland.[8] Importantly, the authors evaluated the severity of persisting pain and followed patients for as long as seven years. Irrespective of age, the prevalence of pain using a broad definition of post-herpetic neuralgia was 19.2% at one month, 7.2% at three months, and 3.4% at one year. Although Helgason et al suggest that the risks of post-herpetic neuralgia have been overestimated their figures are actually higher than the 9.3% risk of pain occurring after rash healing and the 8.0% risk at 30 days found in community studies.[2 9] However, the risks of post-herpetic neuralgia found by Helgason et al are considerably lower than those found in patients treated with placebo in trials of antiviral drugs; in those trials 33-43% of participants had pain at three months and 24-25% had pain at six months.[7 10]

Discrepancies in prevalence

How can these discrepancies in the prevalence of post-herpetic neuralgia be explained? It is well known that mild cases of herpes zoster occur and are often not treated. The trials of antivirals may have been biased by the referral of cases with a higher risk of post-herpetic neuralgia. If so it seems that by referring the more severe cases to clinical trials, general practitioners are selecting those who are at greatest risk for post-herpetic neuralgia; this suggests that it may be possible to identify the patients who most need treatment in the community. Another possibility is that the controlled trials were more sensitive in detecting persisting pain than the study by Helgason et al, in which patients were asked to report the intensity of their pain rather than to indicate whether they had any persisting pain. It is also possible that people in Iceland have a higher tolerance for pain, as has been found in Nepalese porters.[11]

Helgason et al's finding that only 2% of patients reported moderate or severe pain at three months is inconsistent with previous studies in which 9% of patients treated with placebo and 2% of those treated with aciclovir reported moderate or severe pain six months after the onset of a rash.[10] Patients in Helgason et al's study, however, might have been younger on average than those in the aciclovir trials and at less risk of developing post-herpetic neuralgia.

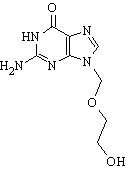

What can be done to prevent or shorten post-herpetic neuralgia? The use of antiviral drugs to treat herpes zoster reduces the duration and prevalence of post-herpetic neuralgia by as much as 500%.[5 7 10] Unfortunately, 20% of patients over 50 years of age treated with famciclovir or valaciclovir in recent trials continued to report pain at six months.[5 7]

Corticosteroids or tricyclic antidepressants have been added to antivirals in an attempt to further reduce the likelihood of post-herpetic neuralgia; however, the data are still equivocal.[12] Other drugs such as topical lidocaine and oxycodone that have been shown to be efficacious in treating chronic neuropathic pain should be evaluated in patients with herpes zoster.[4 12] When using these drugs, treatment should be started as soon as possible after the onset of rash to prevent post-herpetic neuralgia.

Patients who do not respond to treatment should be referred to a pain clinic. Meanwhile, progress in the prevention and treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia will depend on advances in research into the pathogenesis of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia and on identifying more accurately those patients in the community who need treatment.

Anthony L Cunningham director

Westmead Millennium Institute, Westmead, NSW 2145, Australia (Tony_cunningham@wmi.usyd.edu.au)

Robert H Dworkin director

Center for Analgesic Research, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, 2337 South Clinton Avenue, Rochester, NY 14618, USA (robert_dworkin@urmc.rochester.edu)

ALC has been reimbursed for attending a symposium by GlaxoWellcome and SmithKline Beecham via funding for a third party organization.

[1] Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:9-20.

[2] Ragozzino MW, Melton LJ III, Kurland LT, Chu CP, Perry HO. Population-based study of herpes zoster and its sequelae. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982;61:310-6.

[3] Dworkin RH, Carrington D, Cunningham AL, Kost RG, Levin MJ, McKendrick MW, et al. Assessment of pain in herpes zoster: lessons learned from antiviral trials. Antiviral Res 1997;33:73-85.

[4] Cluff RS, Rowbotham MC. Pain caused by herpes zoster infection. Neurol Clin 1998;16:813-832.

[5] Beutner KR, Friedman DJ, Forszpaniak, C, Andersen PL, Wood MJ. Valaciclovir compared with acyclovir for improved therapy for herpes zoster in immunocompetent adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1995;39:1546-53.

[6] Tyring S, Barbarash RA, Nahlik JE, Cunningham A, Marley J, Heng M, et al. Famciclovir for the treatment of acute herpes zoster: effects on acute disease and postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:89-96.

[7] Dworkin RH, Boon RJ, Griffin DR, Phung D. Postherpetic neuralgia: impact of famciclovir, age, rash severity and acute pain in herpes zoster patients. J Infect Dis 1998;178(suppl 1):76-80S.

[8] Helgason S, Petursson G, Gudmundsson S, Sigurdsson JA. Prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia after a first episode of herpes zoster: prospective study with long term follow up. BMJ 2000;321:794-6.

[9] Choo PW, Galil K, Donahue JG, Walker AM, Spiegelman D, Platt R. Risk factors for post herpetic neuralgia. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1217-24.

[10] Wood MJ, Kay R, Dworkin RH, Soong SJ, Whitley RJ. Oral acyclovir therapy accelerates pain resolution in patients with herpes zoster: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:341-7.

[11] Clark WC, Clark SB. Pain responses in Nepalese porters. Science 1980;209:410-2.

[12] Dworkin RH. Prevention of postherpetic neuralgia. Lancet 1999;353:1636-7.

General practice p 794

BMJ 2000;321:778-9

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group