The combination of heightened emphasis on risk and its management in mental health, the precautionary principle, the idea of genetic susceptibility; advances in screening technology and the promise of preventive pharmaceutical intervention is highly potent, especially in a world in which preventive prescription of psychiatric medication has become routine, Psychiatric professionals are given the obligation of governing, and being governed, in the name of risk, and in apolitical and public sphere suffused by the dread of insecurity But there are risks in seekingto govern risk in a biological age, In this paper1 Nikolas Rose argues that the public, politicians and professionals alike might do better to refuse the demands of risk, and learn to live with uncertainty

Key words: risk management biological psychiatry psychiatric medications psychiatric professionals preventive prescription

Few can doubt the pervasiveness of 'risk thinking' in contemporary western societies, This is especially so in areas of health and, of ourse, it takes a particukr form in relation to mental health. There was a time when risk taking was admirable. The greatest rewards came to those who were prepared to take the greatest risks. The persona of the capitalist, the entrepreneur, was that of the risk taker. Some of this positive valuation of risk lives on, of course. A greetings card sent to me a year or so ago has as its slogan 'Risk: the loftier your goals, the higher your risk, the greater your glory' (see also Simon, 2002). Some marvel and celebrate the risk-taking character of those who engage in extreme sports or set themselves the challenge of walking alone to the South Pole. But for most of the time most of us live under the shadow of a different idea of risk: one that carries an entirely negative connotation. Risk is danger, hazard, exposure to the chance of injury, liability or loss. Risk also carries a performative injunction: something to be guarded against, avoided, managed, reduced, if not eliminated. The demands of the precautionary principle - to be seen to act to avoid an imagined future potential harm, despite lack of scientific certainty as to its likelihood, magnitude or causation - seem hard to escape. Note that this is a demand about perceptions and actions in the present; it is not about outcomes.

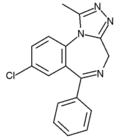

Public health medicine has involved a statistical kind of risk thinking since the 19th century. But risk thinking in medicine takes a particular form in western 'pharmaceutical' societies. Consider, for example, the most prescribed drugs in the US in 2002 (see http://www.rxlist.com/top200.htm). The most prescribed drug was hydrocodone, a pain reliever. Lipitor (Atorvastin), for the treatment of hyperlipidemia, was second. Atelonol, a beta-blocker used for the treatment of high blood pressure, angina and recurrence of myocardial infarction, was third. Synthyroid for the treatment of thyroid deficiency - a condition characterised by general lethargy and lack of activity was fourth. Premarin, for the treatment of symptoms of the menopause (hormone replacement therapy), was fifth. Viagra came in at only 41, up sixpkces from 1999. As for psychiatric drugs, Alprazolam (Xanax), for the management of anxiety disorders, was the most used, at eleventh, sertraline (Zoloft) was at number 13, and paroxetine (Paxil) was fifteenth.

A few things stand out from this list. First, obviously, these best sellers are drugs that are prescribed chronically rather than acutely. Second, these are drugs that do not so much treat an illness as manage the troubles inherent in human life. Third, many of these drugs do not treat diseases at all: they are targeted at risk itself. The treatment of risk itself emerges, initially, from epidemiology. Epidemiological evidence is aggregated into risk scales that try to summarise the probabilities of certain kinds of illness for those in certain groups. Assessments of epidemiological risk are usually combined with clinical assessments of risk based on other kinds of evidence. Increasingly, today, these are supplemented with individualised testing, screening and imaging technologies. But much intervention is still treatment of risk. We see routine screening of women for presymptomatic signs of cancer of the breast or cervix, often leading to medical intervention targeted at sites thought to be the precursors of cancer. We see the routine testing of blood lipid levels and the prescribing of lip id-lowering drugs on the basis of risk profiling, with the aim of reducing the likelihood of future heart disease. We see the routine prescription of drugs in response to blood pressure measurements elevated above a conventionally accepted norm. As the medical historian Charles Rosenberg has pointed out, these interventions do not so much treat diseases as 'protodiseases' - conditions that 'have in common their ordinarily symptomless qualities and their dependence on newly shifting diagnostic criteria' (Rosenberg, 2003 ).

Such proto-diseases have often emerged as treatable conditions through the proselytising activities of individual medics or sub-specialties. They also arise from disease awareness campaigns by patient groups. Sometimes, by no means always, these are supported by the pharmaceutical companies who have the patent for the relevant drug. Treatment of proto-diseases treatment of risk -has become a valuable and growing market. There is currently major investment in research aimed at genomic-based, pre-symptomatic diagnosis, through which, potentially, we may all be revealed as asymptomatically ill. Perhaps, some hope, we may be on the threshold of a new form of public mental health that will be based on such pre-symptomatic screening for risk of mental health problems, coupled with intervention undertaken in the name of prevention. I will return to this later. But for now, we can be fairly certain that the treatment of 'the disease of risk of disease' itself will become even more central to western health systems.

The most widely prescribed of the new generation of psychiatric drugs also treat risk. They are prescribed chronically, in the name of the prevention of relapse. The greatest risk, it seems, is that patients, believing themselves well, or in response to the adverse effects, stop taking the drug. Hence this kind of risk leads to the focus on drugs that will maximise compliance, or adherence, and strategies to increase this: the hope, today, placed in pharmacogenomically-tailored medication. Risk-targeted prescribing in psychiatry accounts for at least some of the rather spectacular recent growth in the use of psychopharmaceuticals. For example, the number of antidepressants and mood stabilisers prescribed in the UK has doubled in the decade from 1993, including a seven-fold increase in the use of SSRIs (figures supplied by IMS Health).

So we do not need to turn to behavioural genetics or brain imaging to see the impact of contemporary biological ways of thinking on the government of risk in psychiatry. Maybe there are some clinicians who will discontinue medication at the end of an isolated episode of disease. But for very large numbers of individuals, not just in the US but in the UK and across Europe, routine, chronic use of psychopharmaceuticals - often in multiple combinations, with others added in when the current mix is seen to be failing - has become routine in the attempt to reduce risk. Evidence is accumulating that questions the value of pre-emptive interventions in other fields of medicine, such as breast cancer. Perhaps it is time to consider the risks of the large-scale social experiment that is entailed by psychopharmaceutical risk management on such a scale.

Risk thinking in mental health

Turning to a different but rekted aspect of this question, mental health legislation and procedures in almost all western countries are pervaded by risk thinking. The question of risk to others is a central concern of the proposed UK mental health legislation (Department of Health, 2002).2 The foreword to the 2002 consultation document recognises that that only 'a very few' people pose a risk to others 'because of their illness'. But, nonetheless, the focus of the proposed legislation is on risk assessment, risk management, risk communication between professionals and agencies, psychiatric treatment of mentally disordered offenders to reduce the risk of re-offending, and, of course, the use of the mental hospital as a site for the detention of those thought to pose a risk to 'the public', irrespective of whether they are 'treatable' and for as long as this risk of serious harm to others is judged to persist.

It is well known that there are many technical problems in predicting a rare event, especially when the base rate of such events within the population is extremely low - as it is with violent acts committed by those of us who have received inpatient treatment for mental health problems. In his recent book Reckoning with Risk, the historian of statistics Gerd Gigerenzer quotes the infamous estimate made for the US Supreme Court by John Monahan in 1980: the 'best estimate is that two out of three predictions of long-term future violence made by psychiatrists are wrong' (Monahan, 1981). In this research, now over 20 years old, in only one out of three cases in which psychiatrists predicted violence did violence occur, despite the fact that the subjects were institutionalised populations with a history of violence and a mental illness diagnosis. Monahan estimates that the reverse error - to wrongly predict there will be no violent act - is much less frequent, and seems to occur in about one out of ten cases. His influential 1993 paper with Steadman and others, entitled 'From Dangerousness to Risk Assessment' (Steadman et al, 1993), argued for a shift away from a binary and fixed distinction dangerous/not dangerous - in favour of a continuous, day-to-day risk assessment involving locating the potentially risky person at the appropriate point on a continuum. In the decade since that time, they and others have sought to shift from 'clinical' to 'actuarial' techniques for judging risk. As they put it: 'If an actuarially valid array of risk markers for violence could be reliably identified, clinicians could be trained to incorporate these factors into their routine practice, and the accuracy of clinical predictions of violence among the mentally disordered would be commensurately increased' (Steadman et al, 1993). In their early work, Monahan and Steadman were concerned to reduce the threat to civil liberties resulting from the over-diagnosis of psychiatric patients as dangerous. It is ironic, then, that the current political demand for risk assessment concerns too little detention, not too much.

The whole point of the shift from dangerousness to risk was the recognition that behaviour is a product of multiple dynamic factors in a complex situation. The mental health status of the specific individual dissolves into this complex of factors: housing, employment, marital status, substance misuse and the like. The point about such factors is that they are not inscribed within the person. They are not diagnoses based on symptoms of illness. And they vary across time and space. This conception of the s ituational genesis of violence maybe accurate. But to actualise it in practice would require a quite impractical continuous monitoring of the everyday life of the 'community mental patient'. So the reality is inescapable. Actuarial risk assessment undertaken at specific points in time can only have limited success in predicting whether an individual will commit an act of violence in the indeterminate future. Indeed, based on their examination of public inquiries into homicides by people with mental illness, Munro and Rumgay (2000) argue that improved risk assessment has only a limited role in reducing homicides, and that more deaths could be prevented by improved mental health care, irrespective of the risk of violence.

There is a second well-known paradox of the use of actuarial predictions of risk of harm to others in those with a psychiatric diagnosis. Why apply it to those with a psychiatric diagnosis and not to others? Some researchers, using conventional research methods such as cohort studies, claim to find clear evidence of a strong relation between severe mental illness - notably schizophrenia - and violent offending (see, for example, Brennan et al, 2000). However other work seems to show that the prevalence of violence, and the type and location of violence, among discharged psychiatric patients is about the same as others living in their communities, except where substance abuse is involved (Steadmanec al, 1998). Some, notably Paul Mullen, have suggested that this arises from the particular national mix of diagnoses that were included in the study. More generally, Mullen (2000) has argued for a move from actuarially-based risk assessments - seeking to predict and control dangerousness - to a clinicallybased therapeutics of risk management - motivated by the wish to provide care and support. Others, notably George Szmukler (for example, Szmukler & Holloway, 2000), have pointed out the inherent injustice of the application of such actuarial measures to particular groups of persons. We do not subject to risk assessment all people who have been involved in violent incidents, nor all those who misuse substances or who have been involved in road traffic accidents.

Even if there is a link between certain types of mental illness and some violent incidents, this does not in itself explain why this should generate such public, political and professional demand for risk assessment in psychiatry. How, then, can we account for the prevalence of risk thinking in the governance of psychiatry?

Does this upsurge of risk thinking arise from changes in the nature or prevalence of mental ill health today? Or does it flow automatically from the move to community based mental health care? Neither of these explanations would be adequate. The sociologist Niklas Luhmann (1993), in his book Risk: a Sociological Analysis, points out that the world itself ;knows no risks, for it knows neither distinctions nor expectations, not evaluations, nor probabilities - unless self-produced by observer systems in the environment of other systems'. In other words, risk arises from particular ways of thinking about, seeing and practising upon the world. This is a point also made, most famously, by Douglas and Wildavsky(1982):'... each form of social life has its own typical risk portfolio.' A risk portfolio is a way of selecting, out of allpossible, real or imagined threats and harms, those that will be the focus of individual or collective attention. This selection is, inescapably, done in relation to moral evaluations pervaded by cultural norms. We know from recent surveys that there is a very strong public perception in many countries that mental illness carries the risk of violence towards others: a perception that is exacerbated by sensational media reports. We know too that this, rather than any increase in actual harms, underlies the promulgation of laws and other measures to focus risk assessment and risk management on psychiatric patients. But what are the cultural norms and moral evaluations that place the risks of those in this heterogeneous category so high in the risk portfolio of the public, the media and politicians?

Perhaps this can be understood, in part, by the ways in which risk thinking in psychiatry brings together two rather different senses of risk. In the first, as we have seen, there is a continuum of risk. In principle we can all be placed on this continuum for - given certain circumstances - each of us might commit violent acts, and those who are young, male and consume alcohol might find ourselves rather high on such a scale. However the arbitrary categories of persons placedhigh on the scale in our contemporary 'risk portfolio' emerge from another, older sense. This is not a continuum but a binary opposition between the normal and the abnormal. In this opposition, some people are fundamentally different: they are 'monstrous individuals'. A monstrous individual is an anomaly, an exception. This is not merely one who diverges from a norm, but one who is of a radically different nature, implacably pathological, evil. These are the 'predators' of popular imagination - sex offenders, paedophiles, serial killers and, as the newspapers would put it, deranged mental patients freed to kill again. And, of course, these are the people with 'severe and dangerous personality disorders' who apparently escape both mental health and criminal legislation, and who must be detained, it seems, under a mental illness diagnosis, so long as they pose 'a grave risk to the public'.

I have no wish to deny that there are many unpleasant and dangerous characters in this world. But what is the threat that generates this fear of suchviolent or predatory monsters out of all proportion to their actual contribution to violence or harm? To place this fear in statistical context, in 2001 there were some 3000 deaths from transport accidents, 2000 deaths from falls in the home, perhaps as many as 4500 deaths from suicide, and between 600 and 750 deaths from homicide, depending on the method of calculation (Office of National Statistics, 2003).

I suspect this is something to do with that apparently harmless category of 'the public'. We the public are not sex offenders, paedophiles, murderers or psychiatric patients - are we? In this way of thinking, there is a primordial division between 'we, the public' and all that threatens us. On the one hand there are fantasies of security, imagined communities within which 'normal' individuals and families might and should be free to live an untroubled life of freedom. But these imagined communities of the normal and the civilized are troubled by the constant threat of predatory monsters. A host of measures respond to this perception - gated communities, closed circuit television cameras, the use of architectural devices, all designed to exclude or expel those who are unable or unwilling to be affiliated to civility in this way. The demand for risk management of those who have a psychiatric diagnosis is one more way of seeking to manage the insecurities that the fantasy of security itself generates and intensifies. Risk assessment has a significance that is more symbolic than instrumental; it answers not to the reality of dangers but to the politics of insecurity. The repeated attempts to define, distinguish and detain those imaginary threats seek to reassure 'us' that 'something is being done', or, rather, seek to ward off media-amplified allegations of complacency and abdication of responsibility. But, like all such defences, they will never achieve their ambitions, for no action of this type could ever be sufficient to counter such imaginary anxiety; attempts to do so, by colludingwith that anxiety, merely exacerbate the very public insecurity that they seek to assuage. But nonetheless, for those who are the targets of such measures, and indeed for all with mental health problems, their consequences are far from imaginary.

I call these developments 'governing through madness'. By this I mean the ways in which contemporary politics of mental health have come to be structured in relation to a more general demand for a politics of community protection and public defence. Psychiatry itself has been re-oriented within these strategies of control formulated in terms of risk. To satisfy the public and political demand for the identification of the potentially monstrous, psychiatric risk thinking has come to connect up the routine management of those with a history of psychiatric troubles with the problem of the identification of the exception. Risk assessment in the name of the prevention of relapse has become entwined with strategies for pre-emptive intervention in the name of community safety. The dream- or nightmare - is that it is possible to identify and exclude those who are incorrigibly risky and potentially monstrous: in short, incarceration without reform. Historical precedents would suggest that such strategies are unlikely to reduce the overall frequency of the very rare incidents they seek to prevent. But they are likely to result in thresholdlowering and net-widening, and the detention of many individuals who would otherwise be capable of leading lives that might sometimes be troublingly different but would pose no dangers to others. These developments should be understood in the context of other moves towards widespread screening for early signs of mental disorder, coupled with preventive intervention, to which I will return later in this paper.

Governing risky professionals

Gerd Gigerenzer subtitles Reckoning with Risk (2002) 'learning to live with uncertainty'. Now we can be uncertain about the date of the declaration of the first world war, uncertain about the precise location of Kyrgyzstan, uncertain about whether we are loved by our partners, or uncertain if five is a perfect number. But in the sense that Gigerenzer means it, uncertainty has a definite temporality. It refers to the future - to an outcome or an occurrence that is, as the OED puts it, 'not determined or fixed; liable to change, variable, erratic'. Gigerenzer's dissection of the confusions besetting public and professional understandings of risk and probability is a model of clarity. But I think he is wrong about one thing: 'risk thinking' is not about 'learning to live with uncertainty' - it is about refusing to live with uncertainty; trying to tame uncertainty, to discipline it, to master and control it. In the phrase made famous by another historian of statistics, Ian Hacking, risk thinking is a way of trying to 'bring the future into the present and make it calculable' (Hacking, 1990). And once it seems one can manage the future by calculated decisions and actions in the present, one pretty soon is obliged to do just that, and is held culpable if one does not.

Luhmann, in the book I cited previously, argues that risk thinking highlights the question of decision - the decision to act or not to act. Who is obliged to undertake this decisional task, and why? Gigerenzer, perhaps unwittingly, shows us the answer. He takes seven examples to illustrate the possibilities andpitfalls of 'understanding uncertainties in the real world': breast cancer screening, informed consent, AIDS counselling, domestic violence, forensic expertise in the courtroom, DNA fingerprinting, and 'violent people'. All are crucial issues, of course. But what is not immediately obvious is that, in each case, the person who has to do this work with uncertainties is a professional. Risk is about professional decisions. It is professionals who are accorded the responsibility for bringing the future into the present and making it calculable. And it is professionals who are held responsible for the consequences of decisions based on such calculations. The target of our current epidemic of risk thinking is thus, not so much the risky individuals and events themselves, but the professionals who have the obligation to manage them.

Did professions always have risk thinking at their core? Certainly professionals were always those who would advise about, guide and manage the present in the name of a better future - except perhaps for 'the oldest profession'. But until recently their advice rested on their authority, on the wisdom inscribed within the professional him or herself as a result of training, experience, and a certain ethic. Luhmann suggests that risk-oriented society arises, in part, out of the expansion of knowledge itself. Knowledge opens up the options andhence makes choice possible. The more knowledge, the more choice; the more choice, the greater need to weigh up options. Hence, he suggests, the enhanced role of risk calcuktion as a way of assessing options. This may be part of the answer.

Another part has to do with trust. What is trust? Luhmann suggests trust is a way of reducing social complexity. It enables us to simplify the decision as to how to act in the present in relation to the future. We vest - or we used to vest - that decisional responsibility in others. It is clear that, in the UK and Europe at least, individuals are increasingly distrustful of this strategy of trust. A wealth of evidence demonstrates that trust in expertise has declined over the last half century: trust in experts, in systems, in procedures and in institutions. The reasons for this are disputed. Some point to specific failures: the failure to prevent the spread of HIV through blood; the failure similarly to prevent human deaths from BSE-related CJD. Others say that such failures are not themselves new, and the roots of distrust lie in increased knowledge, the decline of deference, the rise of aggressive 'active' individualism, or rivalrous disputes amongst experts themselves.

My focus is on a different question. How do professionals cope when that trust is lacking? When their powers, capacities, and reliability are disputed by a distrustful alliance of politicians, professional rivals, academics and public opinion? Some say this arises because the public suffers from a deficit in understanding, which must be remedied by education. Others say that the trust deficit is to be remedied by communication, participation, democratic dialogue. But an older strategy is for experts to try to regain their lost image of objectivity. And a familiar tactic is for the professionals to enwrap their judgments in numbers. This is the argument of another historian of statistics, Theodore Porter: when profess ionals are weak, they seek to surround themselves with the aura of objectivity provided by numbers (Porter, 1995). When the authority of expertise, the wisdom of the professional, is trusted, they have little need for numbers. The greater their need for numbers, the weaker - politically - they become. When a decision is justified by a number on a scale, all the assumptions, choices and judgements that have gone into the compilation and standardisation of such scales are 'black boxed'. They become invisible, enmeshed within the single figure-a 90% chance, a risk of one in five, or a probability of less than one in ten thousand.

The power of the single figure is hard to resist. It provides a guide to action. But it also provides a legitimation of that action, when challenged. Evidence from the UK suggests a certain reluctance among psychiatric professionals to render risk into numbers, however much this is advocated by risk managers. But the very act of risk assessment - a formal, documented, auditable procedure, even if it only results in the allocation to a category (low, medium, high risk) partakes, however reluctantly, of the same impetus.

Perhaps our focus, then, should be less on 'risk culture' than on 'blame culture': that is to say, a culture in which 'there can be no such thing as an accident'. The anthropologist Mary Douglas (Douglas, 1992) has described three types of blaming. We can blame misfortune on the sin of those who suffer: it was their own fault. We can attribute misfortune to the work of individual adversaries, rivals within who seek our discomfort. Or we can blame an outside enemy. Our current blaming system adds a fourth type. We attribute blame not - or not just - to the person who has committed an act but to the authority who should have foreseen and prevented it. Once it seems possible to predict the future through the application of knowledge, once it seems possible to take action in the present to avert a potential unwelcome future, then failure to do so cannot be ascribed to chance. Even a non-decision is a decision. Someone has decided, someone could have decided otherwise, someone is therefore culpable. As Douglas points out: 'We are... ready to treat every death as chargeable to someone's account, every accident as caused by someone's criminal negligence, every sickness a threatened prosecution. Whose fault? is the first question.' She actually says 'we are almost ready' but she was writing in 1991. In the early 20th century, our ideas of social security, social insurance - indeed the social itself-were linked to the notion of a solidaristic society in which accidents, illnesses, even crimes, arose in a regular pattern out of the laws of the social order. At the start of the 21st century, like inhabitants of some imagined primitive society where every misfortune has a reason, the idea of an event not having a motivated cause is hard to entertain.

In what Michael Power, of the LSE's Centre for Risk and Regulation, has termed 'audit society', the shadow of future scrutiny of the grounds for a decision, and potential future culpability, falls heavily back upon all decisions in the present (Power, 1997). The requirement to be able to justify a decision in a future audit mandates a set of auditable and justifiable actions, rules that have been followed, paper trails and so forth. Hence we see the phenomenon that is also observed in other professions, in which the very forms of perception, recording and communication about those in the mental health system by all those who work in it is 'formatted' through the gaze of risk. Often many risk assessments are done on the same patient by different professionals, using diverse instruments, tick boxes and forms. Audit, here coupled with blame, thus reshapes professional actions into an auditable form. The audits, here, not only include the routines of 'clinical governance' but the machinery of the 'public enquiry'. In this sense, the current emphasis on risk assessment is not simply about ways of managing the risk of risky individuals, nor about 'governing communities' by amplifying their perceptions of the risks to themselves posed by people with mental health problems - it is about governing the activities of psychiatric professionals themselves.

Risk in a biological age

Actuarialism is one way of refusing to live with uncertainty. But there is another. This arises from the turn to biology in contemporary psychiatry. This turn has a number of axes. I have already mentioned psychopharmacology. There is also the dream of specificity in the diagnosis of mental ill health embodied most clearly in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (currently DSM-IV). There is the rise of neurochemical models of mental illness - in particular the focus on disorders of the neurotransmitter systems. There are the new hopes (and fears) invested in behavioural genetics in a genomic age. There is the belief that functional brain scanning can individuate mental pathologies in the living brain. Some have suggested that the new biological psychiatry might be able to use some or all of these dimensions to resolve the issue of future liability to violence or anti-social conduct. Would it be possible to identify individuals whose propensity to such conduct arises from genetic or neurochemical anomalies or is, in some other way, inscribed in their biology?

For those who follow this line of reasoning, early diagnosis coupled with preventive intervention may enable individuals so afflicted to be diverted from their path to criminality. For others, such biological and genetic accounts threaten the very idea of free will and responsibility upon which our criminal justice system rests. And for critics, such 'biologisation' of crime is a thoroughly reactionary endeavour, diverting our attention from the social conditions that generate criminal conduct. Research on the biology of violence and impulsive behaviour is especially controversial in the US, where such a high proportion of the criminalised population is African American, as it is thought to reactivate a belief in the innate criminality of certain races.

Of course, there is nothing new in biological explanations of criminality and violence, nor in attempts to argue that these should form the basis for screening, prediction and early intervention. However, from the end of world war two up to the start of the 1980s, they remained at the margins of criminology and had negligible impact on actual practice. How is the situation changing in the context of the recent resurgence of biological psychiatry? Two aspects are worth noting. The first, in the courtroom, is the potential use, and impact, of biological evidence of mental pathology in criminal trials. One case in particular has been well publicised: that of Stephen Mobley, accused of murdering the manager of a Domino's pizza store in 1991. His lawyers sought to introduce genetic evidence-not to support a defence of not guilty but in mitigation of sentence. This was based on a family history that was claimed to show four generations of violence, aggression and behaviour disorder in uncles, aunts and grandparents. The lawyers argued that this was relevant because of Han Brunner's study (Brunner et al, 1993 ), which claimed to identify a syndrome in which borderline mental retardation was linked to abnormal behaviour, including violence and aggression. Genetic linkage studies showed this syndrome to be associated with a point mutation in a gene regulating the production of an enzyme monoamine oxidase A - linked to changes in levels of various neurotransmitters.3

The Brunner study has become something of an exemplar to all future attempts to find a genetic basis and a neurochemical mechanism for impulsive or violent crime. But the court in the Mobley case refused to admit this evidence. The grounds were similar to those used in earlier 'biological' defences - for example the XXY chromosome cases in the 1970s and the premenstrual syndrome cases in the 1980s. That is to say, what needs to be demonstrated for the courts is a reasonably certain causal connection between the biological or genetic condition in question and the specific act of criminal conduct. There is a considerable distance between the probabilistic world of genetic research and the deterministic thinking of the courts. I know of no later cases where this 'genetic defence' has succeeded. The same is true of evidence from brain scans. These are used in personal injury cases in the courtroom where issues of brain injury are involved. PET and MRI evidence of brain tumours has, on at least one occasion, been used successfully to support a claim of insanity. But, to my knowledge, attempts by defence lawyers in the US to use scans to demonstrate 'functional' abnormalities - that is to say, mental illnesses where there is no lesion or injury-have not, to date, passed the test of reliability required for novel scientific evidence to be accepted by the courts in criminal cases.

If such arguments were to gather strength, however, what would be the implications? Not, I suspect, to eliminate the legal fiction of freedom of will. When the judiciary defends the non-genetic, non-psychiatric fictions of free will, autonomy of choice and personal responsibility, this is not because legal discourse considers this a scientific account of the determinants of human conduct (see Rose, 2000). Rather, legal discourse deems it necessary to proceed as if it were, for reasons to do with prevailing notions of moral and political order. Indeed, the trend of legal thought seems to be in the other direction. The emphasis, especially in the US, is on the inescapability of moral responsibility and culpability. No appeal to biology, biography or society will weaken moral responsibility for the act, let alone the requirement that the offender be liable to control and/or punishment. In this context, the argument from biology is likely to have its most significant impact, not in diminishing the emphasis on free will necessary to a finding of guilt, but in the determination of the sentence. This will not necessarily be the mitigation of that sentence: if antisocial conduct is indelibly inscribed in the body of the offender, reform appears more difficult, and mitigation of punishment inappropriate. More likely are arguments for the long-term pacification of the biologically irredeemable individual in the name of public protection. This view seems to be gaining hold, even if it means the rejection of many 'rule of law' considerations, such as those concerning the proportionality of crime and punishment.

The second context where the rise of biological psychiatry is bearing on the issue of risk relates to the belief, notably in the US, that there is something of an epidemic of crimes of aggression, impulsivity and lack of self-control. Violence, here, is becoming defined as a public health problem. In the early 1990s, the US National Institute of Mental Health launched its National Violence Initiative. Psychiatrists would seek to identify children likely to develop criminal behaviour and develop intervention strategies. The official report from this initiative, published in four volumes in 1993 and 1994, called for more research on biological and genetic factors in violent crime. It also called for research into new pharmaceuticals that might reduce violent behaviour (Reiss & Roth, 1993; Reiss et al, 1994). By 1992, the US federal government, in partnership with the Macarthur Foundation, was sponsoring a large-scale initiative entitled the Program on Human Development and Criminal Behavior, to the tune of some $12 million dollars per year. The project aimed at screening children for biological, psychological and social factors that may play a role in criminal behaviour, and proposed to follow subjects over an eight-year period, with a view ultimately to identify biological and biochemical markers for predicting criminality. While this umbrella program was withdrawn as a result of controversy surrounding the violence research initiative, individual projects from the program continued to be sponsored by the federal government.

While critics see this as a dangerous programme of social control, most doubt that genetic and biological explanations will ever play a significant role in strategies for the prevention of violence. In 1996, however, Diane Fishbein of the US Department of Justice argued that: Once prevalence rates are known for genetically influenced forms of psychopathology in relevant populations, we can better determine how substantially a prevention strategy that incorporates genetic findings may influence the problem of antisocial conduct.' At a minimum, she believed, the evidence 'suggests the need for early identification and intervention' (Fishbein, 1996). As Daniel Wasserman (1996) has pointed out, biological criminologists hope that neurogenetic research into anti-social behaviour, while it will not discover 'causes', might identify markers and genes associated with that behaviour. Thus, for example, in 2003, Evan Deneris and colleagues at case Western University, working with mice, reported the discovery of the Pet-lgene - only active in serotonin neurones which, when knocked out, produced elevated aggression and anxiety in adults compared to wild type controls (Hendricks et al, 2003 ). The case Western press release, headed 'Researchers discover anxiety and aggression gene in mice; Opens new door to study of mood disorders in humans', pointed out that: 'Serotonin is a chemical that acts as a messenger or neurotransmitter allowing neurons to communicate with one another in the brain and spinal cord. It is important for ensuring an appropriate level of anxiety and aggression. Defective serotonin neurons have been linked to excessive anxiety, impulsive violence, and depression in humans... Antidepressant drugs such as Prozac and Zoloft work by increasing serotonin activity and are highly effective at treating many of these disorders.' And Deneris himself comments: 'The behavior of Pet-1 knockout mice is strikingly reminiscent of some human psychiatric disorders that are characterized by heightened anxiety and violence'.4

Thus it is possible to imagine, at least in principle, programmes of screening to detect individuals carrying these markers. Pre-emptive intervention might be planned to treat the condition or ameliorate the risk posed by the affected individual. The most likely route is one with which we are already familiar: the use of psychopharmaceuticals to reduce risk. Biological expertise could thus be the basis of risk prevention strategies by a variety of agencies of social control. While full-scale screening of the inhabitants of inner cities might be too controversial to contemplate in most jurisdictions, the example of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, at least in the US, suggests the possibility of genetic screening of disruptive schoolchildren, with pre-emptive treatment a condition of continuing schooling. Or one might imagine post-conviction screening of petty criminals, with genetic testing and compliance with treatment made a condition of probation or parole. Or one can envisage scenarios in which screening and therapy are offered to disruptive or delinquent employees as an alternative to termination of employment.

There are suggestive precedents here. Many psychiatric medications - for example antabuse for alcoholics and lithium for manic depression - were introduced in this way in the US. And, retrospectively, biological expertise might be called upon to screen for genetic markers and neurochemical abnormalities, in order to evaluate the levels of risk posed by offenders, or non-offenders with a mental illness diagnosis prior to discharge from prison or hospital. Release would be dependent on compliance with a drug regime. This scenario is hardly science fiction.

Conclusion

In these claims to discover the person genetically at risk we are seeing the emergence of a new 'human kind': the person biologically at risk of being the perpetrator of aggression or violence. But biology here is not destiny. As in other areas of contemporary genomics, the relation between biology and criminality is being posed in terms of 'susceptibility' (see Hacking, 1992). The dream-once susceptibilities have been identified-is of preventive intervention. The combination of risk thinking in mental health, the precautionary principle, the idea of susceptibility, the emergent technologies of screening, and the promise of preventive medical intercession with drugs is potent, especially in a world in which the preventive prescription of psychiatric medication has become routine. It becomes still more potent when placed in a context in which psychiatric professionals are given the obligation of governing, and being governed, in the name of risk, and even more when it is embedded in a political and public sphere suffused by the dread of insecurity. But perhaps we need to pause, and to ask ourselves: what are the benefits, and what are the dangers? What are the risks of seeking to govern risk in a biological age? Would it be too much to suggest that we-public, politicians and professionals alike-might do better to refuse the demands of risk, and learn to live with uncertainty?

1This is a revised version of a paper given as the opening keynone address to the faculty of Forensic Psychiarty, Royal College of Psychiatrists' Annual Conference, 4 February 2004.

2 In the UK, the consultation document on the Draft Mental Health Bill of June 2002 makes an interesting distinction between danger and risk. 'Some people...,' the ministers say in their foreword, 'because of their illness, can be a danger to themselves others.' This distinction of danger and risk in not sustained in the arguments around the Bill.

3 In a later paper, Brunner (1996) discusses the implications of his research m rather different terms.

4 Viewed at http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2003/01/030123072840.html

REFERENCES

Brennan PA, Mednick SA, Hodgins S (2000) Major mental disorders and criminal violence in a Danish birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry 57 494-500.

Brunner HG (1996) MAOA deficiency and abnormal behaviour: perspectives on an association. In: Bock GR, Goode JA. Genetics of criminal and antisocial behaviour. Chichester: John Wiley.

Brunner HG, Nelen M, Breakefield XO et al (1993) Abnormal-behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase-A. Science 262 578-580.

Department of Health (2002) Mental Health Bill. Consultation document. London: Department of Health, 2002.

Douglas M (1992) Risk and blame: essays in cultural theory. London: Routledge.

Douglas M, Wildavsky AB (1982) Risk and culture: an essay on the selection of technical and environmental dangers, Berkeley/London: University of California Press.

Fishbein DH (1996) Prospects for the application of genetic findings to crime and violence prevention. Politics and the Life Sciences 15 91-94.

Gigerenzer G (2002) Reckoning with risk: learning to live with uncertainty. London: Penguin.

Hacking I (1990) The taming of chance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hacking I (1992) World-making by kind-making: child abuse for example. In: Douglas M, Hull D (eds) How classification works: Nelson Goodman among the social sciences. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Hendrick TJ, Fyodorov DV, Wegman LJ et al (2003) Pet-1 ETS gene plays a critical role in 5-HT neuron development and is required for normal anxiety-like and aggressive behavior. Neuron 37 233-247.

Luhmann N (1993) Risk: a sociological theory. New York: A de Gruyter.

Monahan J (1981) The clinical prediction of violent behavior. Washington DC: Government Printing Office.

Mullen PE (2000) Forensic mental health. British Journal of Psychiatry 176 307-311.

Munro E, Rumgay J (2000) Role of risk assessment in reducing homicides by people with mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 176 116-120.

Office of National Statistics (2003) Mortality statistics: injury and poisoning. Series DH4 No 26. London: Office of National Statistics.

Porter Theodore M (1995) Trust in numbers : the pursuit of objectivity in science and public life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Power M (1997) The audit society: rituals of verification. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Reiss AJ, Roth JA (1993) Understanding and preventing violence: report of the National Research Council Panel on the Understanding and Control of Violent Behavior. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Reiss AJ, Roth JA, Miczek KA (1994) Understanding and preventing violence: report of the National Research Council Panel on the Understanding and Control of Violent Behavior. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Rose N (2000) The biology of culpability: pathological identity and crime control in a biological culture. Theoretical Criminology 4 5-43.

Rosenberg C (2003) What is disease? In memory of Owsei Temkin. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 77 491-505.

Simon J (2002) Taking risks: extreme sports and the embrace of risk in advanced liberal societies. In: Baker T, Simon J (eds) Embracing risk: the changing culture of insurance and responsibility. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Steadman HJ, Monahan J, Robbins PC et al (1993) From dangerousness to risk assessment: implications for appropriate research strategies. In: Hodgins S (ed) Mental disorder and crime. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J et al (1998) Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55 393-401.

Semukler G, Hollway F (2000) Reform of the Mental Health Act: health or safety? British Journal of Psychiatry 177 196-200.

Wasserman D (1996) Research into genetics and crime: consensus and controversy. Politics and the Life Sciences 15 107-109.

GENETICS

Nikolas Rose Professor of Sociology/Director,BIOS Research Centre London School of Economics and Political Science

Correspondence to: Nikolas Rose BIOS Center London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE n.rose@lse.acuk

Copyright Pavilion Publishing (Brighton) Ltd. Sep 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved