Diuretic Slows Cystic Fibrosis Damage

An aerosol form of a diuretic drug slackened the pace of lung damage in 14 young adults with cystic fibrosis, scientists report. Their pilot study raises hopes for an improved treatment for adults suffering from this as-yet-incurable disease. It also suggests that physicians may one day treat children with the inherited disorder before serious lung-tissue destruction occurs.

"This is the first time a drug has been developed to treat the primary cystic fibrosis defect," says Robert J. Beall, executive vice president of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation in Bethesda, Md. Standard treatment today consists of antibiotics to combat lung infections and physical therapy to clear thick secretions from the airways, but physicians have had no way to thin the abnormal mucus that characterizes the disease.

Previous research had identified the defective gene causing cystic fibrosis, inherited by one in every 2,500 U.S. infants (SN: 9/2/89, p.149). This genetic flaw causes epithelial cells lining the lung's airways to absorb excessive amounts of salt and water, leaving airway secretions thicker than usual. People with cystic fibrosis can't clear away the sticky mucus, which hosts repeated infections that destroy more healthy lung tissue, eventually resulting in death.

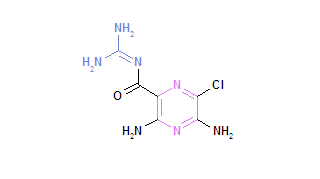

Michael R. Knowles and Richard C. Boucher of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and their co-workers now report early evidence that the diuretic amiloride blocks absorption of salt and water at the epithelial cells, thinning the mucus and improving the patient's ability to cough up secretions. They present their findings in the April26 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE.

The team studied cystic fibrosis patients aged 18 to 34, giving them antibiotics at the study's start to clear any festering lung infections. Seven of the 14 volunteers inhaled a spray form of amiloride four times daily for six months, while the other half received a placebo spray. After six months, the team gave all patients another round of antibiotics and then switched each person to the opposite treatment.

Sputum samples showed that mucus was more fluid during amiloride therapy than during placebo treatment, the researchers report. Moreover, in analyzing a year's worth of data, they discovered that when patients got amiloride, the average loss of lung function from mucus buildup dropped by about 50 percent, with no adverse side effect. "We slowed the normal disease-induced loss of lung function," Boucher told SCIENCE NEWS.

Amiloride doesn't heal damaged lung tissue, but it does appear to protect remaining lung tissue from infection by thinning sticky secretions that can become breeding grounds for infectious microbes, Knowles says. The study suggests amiloride may keep adults with cystic fibrosis infection-free for long periods, thus preventing frequent trips to the hospital, Boucher says. The researchers hope such treatment may prolong the lives of people with cystic fibrosis, but further study must demonstrate that benefit, Knowles adds.

The preliminary report hints that physicians might one day prevent permanent lung-tissue damage before it occurs by giving amiloride early in life, says Susan P. Banks-Schlegel of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md. But she cautions that further research is needed to establish the drug's safety and efficacy, especially in treating children. Adds Knowles, "We don't want doctors and parents running out and using this drug willy-nilly in children before the appropriate safety studies have been done."

Physicians currently prescribe amiloride pills--which do not work in cystic fibrosi--to treat adults with high blood pressure. But the FDA will require additional tests before approving the aerosol version as a treatment for cystic fibrosis. Knowles says he is planning a second amiloride study, this one to include some teenagers.

COPYRIGHT 1990 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group